Cover photo: ©Maryam Ashrafi

It isn’t easy to talk about political music in Europe or the West. These are challenging times, and political music reflects a crisis of leftism and many political movements. It’s true for many countries. It’s true for Italy. But it was not always so. There are several examples throughout history of how political struggles intertwined with the world of music. They cross-contaminated each other and grew, regardless of the logic of profit, that came to dominate the industry and society.

In the 1970s, the world of rock and songwriting was steeped in the political scene and struggle; many artists and singers were also part of collectives and often militant members of politically active organizations. In the 1990s, the counterculture scene marked the return of punk in its melodic hardcore version; this period also saw the burst of grunge, the counterculture scene was marked by a melodic hardcore version of punk and the sudden explosion of grunge and rap as well as the advent of cross-over. Alongside them, we saw a creeping and expansive emergence of ska, patchanka, drum’n’base, jungle, and reggae, whose place of birth was in community centers, squats, underground clubs, and self-financing parties. The rave movement also changed and moved away from its original form. Participants claimed spaces of physical and personal freedom as they squatted in abandoned spaces and used them for music parties that could last for days on end. They also experimented with various substances on their bodies.

This overlap between politics and music experiments has been vastly lost. We are in a phase where capitalist violence has subsumed countercultures. It has shaped them and slowly emptied them of political meaning while placing monetary value on them.Capitalism prevents the explosion of cultural/political phenomena and gives space to the most innocuous musical forms that are only good for generating profit. Dominant music is not inspirational; it doesn’t tackle society’s problems or challenge toxic social norms. It is not composed to give rise to protests, soundtracks, pickets, or riots.

How did we get here? The responsibilities are widespread among artists, producers, and industries. Many independent labels were either assimilated into music majors or shut down. Artists, who also needed to make a living, were absorbed into this new model and didn’t fight back against the industry’s commodification.

In this grim scenario, there are also exceptions.

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the U.S. is an excellent example of how capitalism recuperates movements by inserting itself into the scene to profit from stances, slogans, and political concepts. Capitalism evolves with society, and it always attempts to empty the struggle or at least de-radicalize it.

Starting in 2013 in Florida to protest against the systemic impunity of white policemen who killed unarmed black individuals, BLM shook the American conscience, confronting the racism at the core of society. Since then, millions of people have taken to the streets, and protests have spread across the country and around the world. Many artists joined the struggle and either performed in public or created songs that reflected the movement’s stances. Dozens of black artists, from Kendrick Lamar to Lauryn Hill but also Beyonce, D’Angelo, and many others, turned the moment into an opportunity to politicize their music and performances. These artists created songs that became soundtracks for the movement. At the same time, giant corporations such as Nike appointed the football quarterback Colin Kaepernick as a brand ambassador. In 2016, before a match in the NFL, Kaepernick kneeled during the national anthem in protest of police brutality and racial inequality. His action sparked considerable debate, and he was barred from playing in the league. In 2018, Nike released an advert with Kaepernick with the text “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything.”

A similar dynamic, though not as large, happened during the Occupy Wall Street movement. For instance, Tom Morello — Rage Against the Machine guitarist — and the Nofx band members were spotted going to the streets to sing and write movement anthems.

If one examines another current widespread movement, such as Fridays For Future (FFF), it becomes apparent that radical artists have not emerged. While several artists deal with climate change issues, none succeeded in establishing themselves as a mass social-cultural phenomenon. The market is not interested in giving them space, while underground circles fail to counter the dominant market logic and promote those artists. And they cannot create an alternative platform for those committed to the struggle. Undoubtedly, the history of subjugation of Afro-descendant populations in the U.S. is broader and more entrenched than the environmental movement around Greta Thunberg. This would at least partly explain the stellar distance between the two experiences.

However, we have to be precise. In the past two decades, the experience of FFF has become the norm rather than mainstream artists embracing the cause, such as BLM.

Why did this happen? Several reasons overlap. There is the cultural weakness of the struggle and protest movements and an inability to create a language that can both enthuse and engage. So, none of the radical elements are used by artists, and therefore, hybridizing the dominant culture.

We are in a phase where capitalist violence has subsumed countercultures. It has shaped them and slowly emptied them of political meaning while placing monetary value on them.

Then there is the music industry, which has “learned” to dribble the most radical experiences and selects artists with easily expendable content. In the meantime, it hegemonizes the market by trying to control every aspect of distribution. Today, it is impossible to think that a music label, a television station, or a big publisher would decide to invest in unknown bands, as it happened in the early 90s with the American Rage Against The Machine or the Italian 99 Posse. Both became musical references for the Western movement circuits while simultaneously earning a living by gaining popularity with the general public. Nowadays, to get into the music business circles, bands like these would have to create a power relationship whereby the music business cannot survive without them and, for economic reasons, bring them into the market. We are in a phase where capitalist violence has subsumed countercultures. It has shaped them and slowly emptied them of political meaning while placing monetary value on them.

Meanwhile, social centers or leftist spaces have no longer developed counterculture, especially in Southern Europe. Now separated from these spaces, musicians have lost the possibility of political encounters and hybridization of social concerns. The absence of this contact means that those who do not seek radical content and do not want to deepen their critique of the dominant system do not need to confront resistance by their community.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, we must also consider that the internet was filled with experimentation on several fronts, including other forms of music promotion and the growth of independent music. Now, the internet has become the realm of algorithms, totally controlled by the platform owners and those who finance their economic success. If Myspace created and launched artists such as the Arctic Monkeys — indeed not a political phenomenon — today through Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, or Spotify, it would make it almost impossible to emerge unless advertising increases visibility. The algorithm’s logic also allows content to be conveyed by those behind the machine.

Not everything is lost. Outside the meshes of the West, the feminist and anti-colonial rap is growing and expanding in Latin America. Rebecca Lane, a Guatemalan rapper, sings about being a woman in her society. The Mexican artist Audry Funk is “a mix of rap, feminism, philosophy, and body motive messages.” Ana Tijoux, from Chile, also emerged from the feminist scene, as well as the two Argentinian singers Sara Hebe and Miss Bolivia. All these artists express a cultural movement far from the record market, television, and radio. This more social and political phenomenon asserts itself in politicized circles and demonstrations. It is interesting to note how the Latin American feminist wave involves superstars such as Julietta Venegas or Karol G.

This feminist wave of musicians was inspired by the movement Ni Una Menos [Not One Less] and managed to unite radical politics and culture throughout Latin America. The movement’s success demonstrates that economic power does not always have the strength to control social and cultural phenomena in the face of a disruptive emotional push.

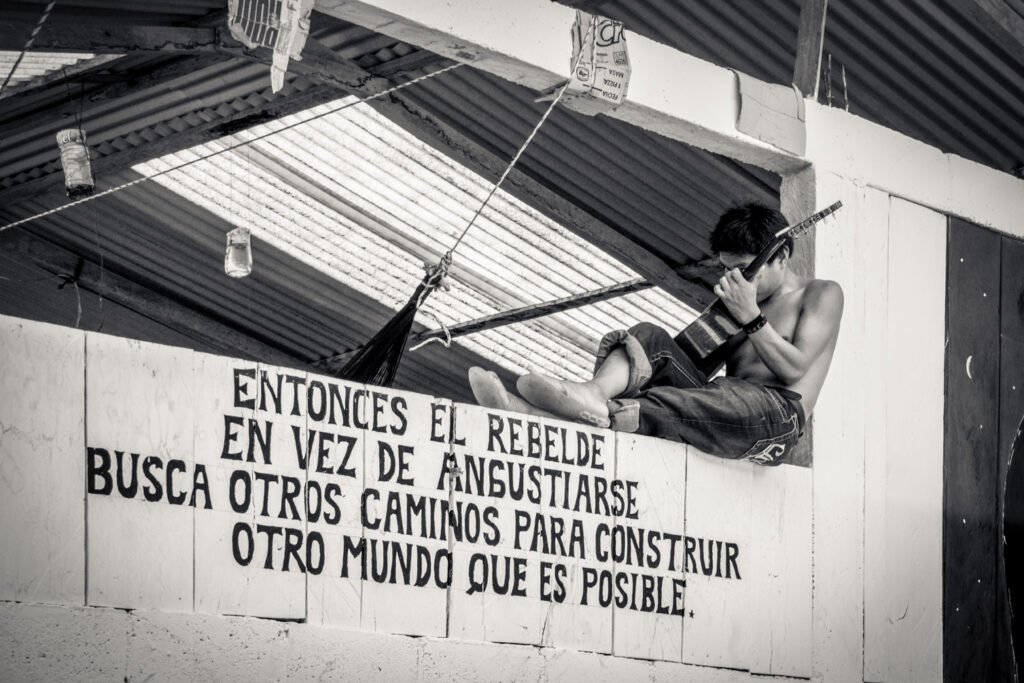

Then, the stories of struggle are rooted in the territories that pose the artistic, cultural, and musical questions central to forming another society. For example, the Zapatista movement in Chiapas has repeatedly organized festivals of anti-capitalist culture, convening groups and artists from different parts of the world but, above all, fostering internal growth within communities. So much so that today, in almost all of the Zapatista territory, bands and artists in different spheres are trying their hand at artistic and cultural production. Last January, for the 30th anniversary of the start of the revolution, the EZLN celebrated with a four-day festival. The first two days, the indigenous community exhibited musical and theater pieces. Internationalists and guests could take to the stage and perform in the following days.

In the past decade, the Revolution in Rojava has sparked the imagination of people worldwide. They did so through music and art while fighting ISIS, the Islamic State, in Syria. Rojava, the Western side of Kurdistan, is part of the Autonomous Administration of Northern Eastern Syria, which is administered through Democratic Confederalism: a self-governing experience that emphasizes people’s participation and work through communes. Since Kurdish was forbidden in the Syrian State, there had been a significant emphasis on music production in their mother tongue. The Art and Culture commune, created in 2012 at the beginning of the revolution, produced dozens of songs in Kurdish that give voice to the struggle, eventually becoming soundtracks for marches and protests around the world.

Today, in the West, the capitalist horde has managed to erase the dream of a different society and has occupied people’s hearts and minds. How far it will be able to prevent a new political/cultural/social wave from exploding is unknown, but certainly, it cannot continue forever. It will be up to the persistent will for change of those who do not accept the status quo and want to fight for alternatives. It will be up to those who wish for a different world, a world not only possible — however much to be imagined — but necessary. However, the need to create a different music scenario cannot be in the head of the artistic world alone. It is also the responsibility of the political and organizational side and of those who try to conceive of music and culture as tools other than mere economic gain. While we must not forget that living in a society dominated by capitalism, cultural work at all levels, and in all its forms, cannot be a hobby but must be recognized and paid for. The constant and persistent shaping, organizing, building, and telling of other and different stories will shape a new future. As Joe Strummer said: “The future is unwritten.”

Andrea Cegna

Journalist born in 1982. Currently a contributor to several Italian newspapers including Il Manifesto, Radio Onda d’Urto, Radio Popolare, Altreconomia, Il Fatto Quotidiano, Desinformemonos. Cegna started by conducting programs at Radio Lupo Solitario, in the province of Varese. He has also written books, the latest “What Happens in the City” for Prospero Editore. He also makes podcasts and documentaries. He tries to look at the world critically, trying to free himself from the colonialist forms with which we are used, in the West.