Cover photo: © Sanger Abdullah Kareem

Maryam Ashrafi, who embraced exile from Iran as a consequence of her photography, mainly focusing on the Kurdish people’s struggle, engages Zehra Doğan in a dialogue regarding her imprisonment and unique form of resistance through art.

While some refer to her as a journalist, others as an artist, and many identify her as a Turkish artist, Ashrafi wonders how Doğan defines herself in this regard in light of her experiences.

Zehra Doğan: I don’t like stereotypes and labels, but if I had to, I would define myself as a ‘Kurdish artist’. I used to work as a journalist, but now I do it differently, by incorporating journalism into my art. In 2010, before my time in prison, while doing journalism and studying art in Diyarbakir, I became a founding member of the Kurdish women’s news agency JINHA.

M: In 2015 and 2016, the Turkish government imposed eight consecutive curfews on the Kurdish-populated city of Nusaybin in Turkey’s Mardin province. For several months, the army deployed heavy weapons and tanks to suppress Kurdish militants in their regional struggle for self-administration; the siege left Nusaybin in ruins.

You said that you were given a prison sentence of two years, ten months and 22 days, merely for your 2016 painting based on a photograph depicting the Turkish military siege of Nusaybin. What was happening there in those days?

Z: From 2012 to 2016, before my arrest because of this painting, I worked as a journalist in Nusaybin with the JINHA agency, while also pursuing my studies in art. Throughout this time, I painted what I witnessed in the city. We experienced a period marked by ongoing curfews, which were occasionally lifted for brief ten-day periods, providing temporary relief. However, a prolonged stretch of uninterrupted curfews eventually left the city empty, except for fighters, journalists, and activists. One of them, Sara Kaya, a Kurdish politician and former mayor of Nusaybin, was sentenced to 16 years in prison and is currently detained in Tarsus prison in Mersin, Turkey.

M: Before we delve further into your prison experiences, could you describe those months under curfew?

Z: It is impossible to describe those days. For almost a year, people resisted and did not leave their homes despite very heavy attacks. However, many were overwhelmed with fear for their safety, after 177 people were shot dead or burnt alive in their basements during Turkey’s military siege of Cizre in February 2016.

In Nusaybin, police announcements over loudspeakers spread fear throughout the city, stating, ‘ This is your last day. Those who wish to leave should do so. A curfew will be imposed.’ This caused many to evacuate their houses and start to leave immediately. It was like joining a massive march. Over a hundred thousand people left the city, and only 100 fighters, a few activists, and three journalists remained.

M: As you know, during those months of curfew, there were many demonstrations in the region to condemn what was happening in Nusaybin, and I remember attending one across the Syrian border in Qamishli on my way to Kobane, in May 2016.

M: So, what led to your arrest?

Z: With every detention or arrest, I was aware the police were also looking for me, due to my consistent reporting from behind the barricades. However, it was that painting of Nusaybin that led to my arrest. After my arrest, I spent five months in Mardin prison awaiting trial. Upon temporary release, still awaiting trial, I exhibited the paintings I had created during my incarceration. Following the actual trial, without immediate custody, I spent several months on the run in Istanbul, where I organised another exhibition and discussions about my prison experience and the Nusaybin events, which led to my re-arrest.

At that time, many civilians and most of the fighters who were imprisoned with me received life sentences. Fortunately, perhaps because I was a journalist, I was among the few who received relatively light sentences.

M: I’m keen on understanding how you employed journalism and art as tools of resistance in such circumstances, all while you were under pressure and unsure about the duration of your imprisonment.

Z: Since I was imprisoned for drawing, I immediately asked my boyfriend, who was a journalist at the time, for drawing materials. He sent me a lot of art supplies, enough for the entire ward. When I began to draw, my fellow inmates in the ward became curious about my art. This interest led me to start giving them lessons in art and in journalism, and we secretly published a newspaper in the prison.

M: Cultural resistance takes shape through various media, including art, poetry, music and more. Your paintings and this newspaper represent a powerful form of resistance. A resistance that not only circulated within the prison; its impact echoed beyond its walls, becoming a topic of conversation and awareness for the general public. Remarkably, you were able to accomplish all of this within the constraints of prison walls. Tell me more about the newspaper.

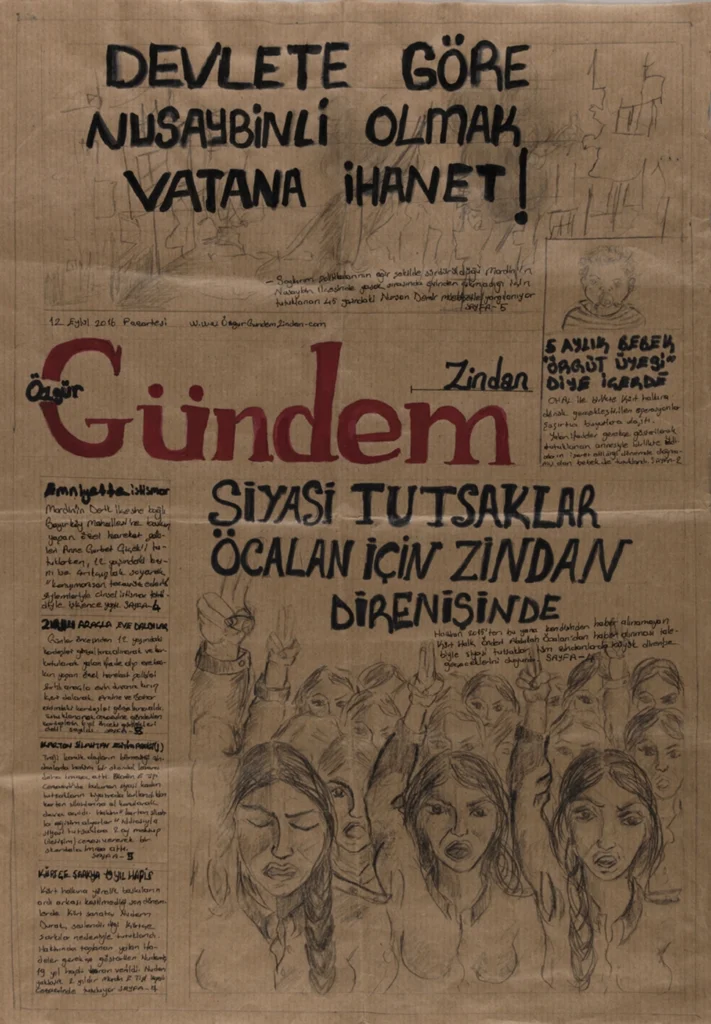

Z: The only thing that keeps you alive in prison is the news on television. Yet, this was only through mainstream media news since the other channels were blocked. Thus, we had only one means of communication to keep us informed about the outside world: the Özgür Gündem, an Istanbul-based daily newspaper.

Severe violations of rights were occurring within the prisons, and as a journalist, I felt a deep sense of responsibility. While the editors of Özgür Gündem outside of the prison were asking for information, recognising the urgency of shedding light on these injustices, we conducted interviews with various inmates and forwarded their stories for publication to them. However, one day, we stopped receiving the newspaper in the prison, which meant we could no longer access information about the outside world nor publicise our voices. After a while, we learned that this was because the newspaper had been raided and closed.

A lot was happening inside the prison, and we were eager to document everything, like cases of human rights violations or torture, particularly involving children. Consequently, my art background inspired the idea of creating our own newspaper.

Because the Özgür Gündem newspaper ceased publication and most of its journalists were arrested, its future became uncertain, and it was as if the newspaper itself had been imprisoned. That is why we called our new secretly published version Özgür Gündem Zindan, Özgur Gündem Gaol.

I taught a small group of my fellow inmates the basics of journalism, assigning them roles such as editors, reporters, and photojournalists. But instead of photos, we used amateur drawings of the people we interviewed. We crafted sections like sports, ecology, life, columns, and women’s issues, resembling a genuine newspaper. Our clandestine fugitive newspaper aimed to share firsthand accounts of human rights abuses in prison and survival guides. We covered everything from handling imprisonment to addressing physical challenges like hair loss, while sharing alternative perspectives and experiences.

M: How did you manage to send your newspaper outside?

Z: I secretly handed it to my sister during her visits to the prison, instructing her to photocopy and distribute it outside, for example, on the university benches. Unexpectedly, we received letters from various countries because the newspaper had also reached a large audience through social media. Praising our resistance, we received messages saying things like: “We take our hats off to your resistance; it’s a very good thing.” As a result of this, soldiers started raiding our rooms every day, unlike before when they would come only once a month. During these raids, they would say: ‘You are publishing a newspaper; where is your equipment?’ But because we did everything manually, the prison authorities, under pressure from the chief public prosecutor, sought the assumed publishing equipment in vain.

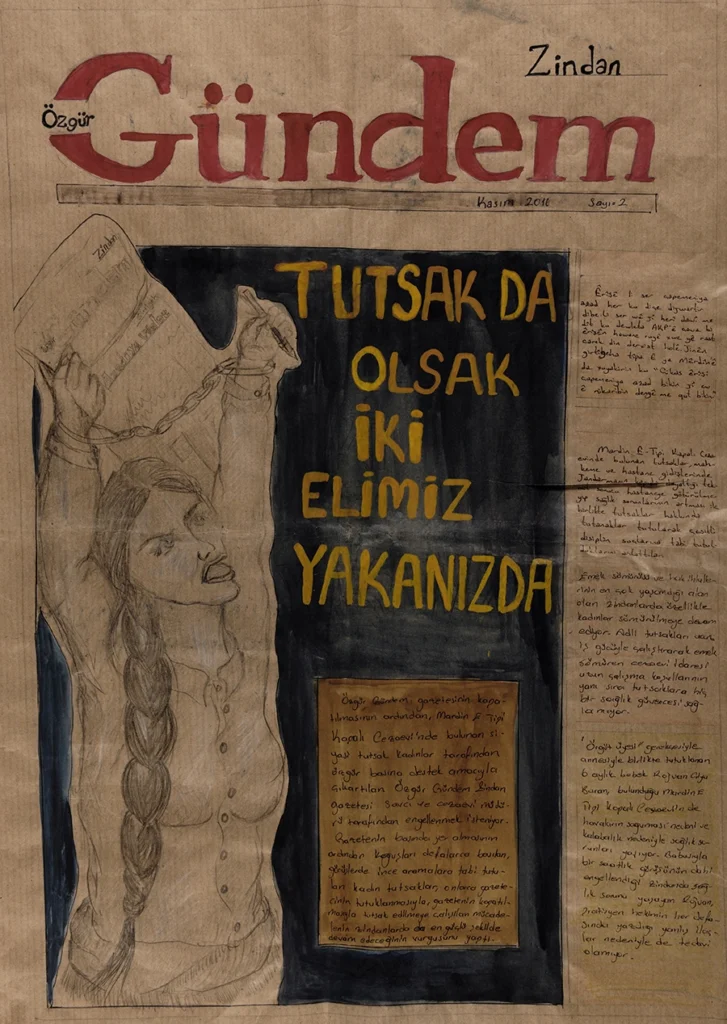

Gradually, my wardmates embraced the idea, and we grew from five people to an entire ward of contributors. Despite restrictions on painting materials and a ban on our journalistic activities, we managed to publish a second issue titled: “Even when in prison, both our hands are at your throat.”

We very much enjoyed that they still could not figure out how we made the newspaper. Upon my release, the warden unofficially expressed relief while hoping I’d avoid future arrests.

M: Was having this use of art as a tool of resistance one of the reasons you once mentioned feeling freer within the confines of the prison?

Z: Imprisonment aims to constrain and weaken. However, inside a paradox unfolds: strength surfaces where weakness is targeted through architectural structures and pressure. Oddly, your body guides you, fostering a newfound, creative mindset. Because of my art background, I expressed this newfound strength through art, while my fellow inmates found their own creative outlets. This is true freedom, ‘the ability to say no’. I experienced the most tremendous sense of freedom in prison because I experienced the confidence of someone who knew how to say no. That’s why I was truly free.

Diyarbakır Prison, where I was held, bore a heavy historical atmosphere. It was initially constructed to rehabilitate and assimilate Kurds into Turkish culture. However, its daunting and sturdy walls were weak enough to be demolished with the blows of women’s hair.

Without access to art supplies, I used the hair of my fellow prisoners to make paintbrushes to create art in order to transmit our reality to the outside world. This act symbolised freedom and power in me — a feeling that I could not find outside. Realising those walls could be demolished in this way gave me a sense of freedom.

M: In 2004, during my visit to Iran, I was arrested on suspicion of being a spy as I intended to start a photographic project about Afghan refugees. Though the project never happened, I was fortunate to be released, a scenario that might not be as likely today. Despite just one night in prison and subsequent court appearances to prove my student status, the experience impacted me. Later, hearing stories from friends and colleagues who had been in Iranian prisons, they often described how they had become impromptu universities. So many intellectuals, activists, teachers and individuals with remarkable experiences and backgrounds are in jail, and leaving prison is not just an escape from confinement with empty hands, but with a wealth of highly valuable and unforgettable experiences. How would you describe your experience before and after prison?

Z: Yes, of course, the same applies to prisons in Turkey. I attended two universities, yet I learned more during my time in prison than in any educational institution. As someone who has experienced prison, I can tell you that a person who has lived in prison is never entirely free or completely captive. Once you’ve been to prison, a part of your soul remains there through your memories and thoughts. I don’t feel entirely free because fragments of my soul, body and energy are still tied to that place. The year following my release was even more challenging than my time in prison. After arriving in Europe with no clear plan or intention to stay long, I was invited to show my work at the Tate Modern in London. After that exhibition, the Turkish police were once again looking for me at my family’s home in Mardin, which made me decide to stay in Europe for now.

M: Sometimes exile is a choice imposed upon you, and sometimes it’s entirely forced. At 17, my family fled Iran because of my dad’s political background. Later, my photography choices and the stories I covered led to losing the option to return to Iran. From then on, I understood that living in exile was my reality.

You arrive with just one suitcase, and suddenly you realise this is your life for an uncertain time. How do you feel? And how do you think this abrupt exile is affecting your work and creative mindset?

You know, it often feels like I’m a bull in Spain, relentlessly banging my head against the wall, injured, bleeding, and unable to find my place.

From the outside, an artist’s life might seem idyllic. Some people might say: ‘They are so nice, always relaxed, and they create beautiful art.’ But for me, it’s more challenging. I’m always dealing with aches and pains, which, of course, can fuel my creativity, but I also feel like an animal constantly shedding its skin. Thus, art is not a very relaxing experience for me.

Maybe afterwards, you feel relief like you’ve given birth to a child, although the pain and labour during the creative process can be excruciating, and I wouldn’t wish for such a talent. Actually, I feel like I’m living in another form of confinement. The exile and all the border barriers make me feel as if I’m living in prison.

M: Is that why you remarked that Erdoğan’s re-election felt like receiving a new prison sentence?

Z: Exactly. It feels like an additional five years have been taken from many people’s lives.

M: And how would you describe the difference in your emotions between exile and imprisonment back in Turkey?

Z: In prison, you feel more motivated because you’re doing something forbidden, something secret, because you want to publicise something. Of course, it was challenging, but at the same time, it was indescribably empowering. Here, it’s more of an isolated feeling as there are very few people on the outside who can genuinely empathise. You need to live it to understand it. I feel tired here. I never felt tired in prison. I barely even slept in prison because time was always running out. Here, there are times when I’m afraid to paint or create art because it brings dark feelings.

In prison, many people are going through the same experiences as you. They understand you, your art and your soul better. They understand your art better than an art critic because they can empathise. Outside, there is a lack of empathy. People pretend to understand, but in reality, they don’t comprehend much. That’s why I don’t even want to attend my exhibition openings, as the audience doesn’t resonate with me at all.

M: Several months have passed since you moved here. Do you still feel that you are in prison in Europe? And during this time, has your art played a role in helping you express and discuss these feelings through your work?

Z: I’ve made a living in Europe and had chances for more exhibitions. Even though I am not mainly motivated by prestigious places like museums, exhibitions, and promotions, this has never been my primary goal, nor have they suppressed my creativity.

I continue producing work because I don’t tie my motivation to one specific time, place, or person. If I were to remain solely in Europe, I would not be able to produce at all. That’s why I have already spent half of my time in Iraqi Kurdistan, closer to my roots.

M: I can empathise with your sentiment, as it mirrors the driving force behind my dedication to a long-term project on the Kurdish struggle. Undoubtedly, my understanding of their fight for their rights and the proximity to a culture and land reminiscent of my home country, Iran, fueled my commitment.

In exploring your work, I came across your powerful performance entitled: You resist me, but I will break you anyway at the Amna Suraka Museum in Sulaymaniah in 2021. This work signifies resistance as a determination to shatter oppressive forces and encapsulates the region’s poignant history.

I have also gathered that we share a similar perspective on defining resistance as the ability to say ‘No’ to something. For me, resisting means saying no to things you wish to change. What do you currently say ‘No’ to these days? And how does this cultural resistance here in exile differ from your experiences in prison and in Turkey?

Z: Here, I continue to resist similar issues, particularly concerning the Kurdish question. Yet, European society also has its challenges. Women experience a form of imprisonment here in a different manner. Many women define freedom in financial terms, associating more money with better choices, and I see women living in a glass prison built by a seemingly benign administrator, while the women themselves often remain unaware of this situation.

The immigration issue is another topic. Politicians gain votes by opposing immigration and by perpetuating stereotypes that paint immigrants as potential criminals. Given my concern for these issues, I engage in both artistic and non-artistic projects here, but I don’t really separate them. I don’t do my art projects for artistic reasons only, as the topics are already part of my way of life. These projects naturally influence my creative work.

For example, I collaborate with communities in Italy and France dedicated to rescuing and supporting migrants. Additionally, I’ve contributed to fundraising efforts by auctioning a painting to support the migrant rescue missions conducted by the NGO Mediterranea Saving Humans.

M: How do you perceive this society?

Z: When I first arrived here, I viewed everyone negatively. I saw Europeans as uninterested individuals who did not meet my expectations in any way. However, I worked on this perception and realised it was unfair to have prejudices against something I did not know. Prejudice is very harmful. In Turkey, the Turks labelled us as terrorists without knowing us, because of their prejudice against me and my people. They harboured hatred toward us without any understanding. For years, they even believed we were creatures living in the mountains with tails on our backs!

I did the same with people living in continental Europe, where I was forced to live. I generalised all Europeans, thinking they were ignorant of global affairs, unaware that the arms factories in their countries were causing harm to many innocent people elsewhere. So, if I’m inclined to make the same judgement about everyone and deem them unintelligent, why should I expect these people to contribute to making the world a better place? During this time, I also learned about many of their ancient spiritual teachings that I greatly admired in their life and cultures.

The policies here are no different from those in Turkey. They are just in a softened form, so people don’t realise they need to fight against them. And that’s why everything has become marketing. Art has become marketing, believing in something has become marketing, having fun has become marketing, and even how you present yourself outside has become marketing. For instance, if you want to turn inward and find spirituality and wisdom, there’s Buddhism for you, and you’ll find numerous yoga studios and meditation programs. In many forests, there are Vipassana camps where you can be silent for ten days and seek spirituality. There’s a great deal of glamour involved, and even as someone who thinks meditation is indispensable, I don’t find this right.

M: Can you tell me more about this and elaborate on it?

Z: I believe that even being an ecologist here is commercialised. People have grown insatiable and need to define themselves through various means. I don’t want to generalise about everyone, but I see all these people in these ‘scenes’, who eat bio, meditate, and think that by defining themselves differently, they will find meaning in life, through a label and qualification.

In Europe, so-called “alternativists” have established themselves as a class of ecologists and yogis, often marginalising others. So, they seem to be doing activism in order to identify themselves with something. They see themselves as ecologists and making alternative art, but where is the soul of all this? Where is the real intention? This is my criticism. As someone with an ecological background, I don’t understand many ecologists here and feel alienated. In my opinion, resistance has become a trend here, but for such important things to become trendy and marketable, to me, is the same thing as fascism.

How many poor immigrant families’ homes have you visited? Have you ever opened your door to an immigrant who had to walk for months? Have you given them your bed so that they can sleep comfortably? Do you know that thousands of immigrants sleep on beach chairs in Germany? And thousands of people who had to flee their country and take shelter here are deported because they cannot express themselves sufficiently when applying for asylum. Why? because there is not even a lawyer to attend their application-meetings, as lawyers ask for very high fees.

With a few friends, we have been looking for months for lawyers for some people who managed to come here, but we cannot find them. We know a few lawyers, but asking them to sit through countless hearings without paying them is unfair. If you look at it on paper, only in Germany there are many NGOs, associations and activists involved in this issue. But where are they? I’ve never yet seen them.

M: I agree that in a world filled with marketing and individualism, taking a moment to reflect on the authenticity of our actions is crucial. On that note, is there anything else you’d like to reflect on before we conclude?

Z: Well, maybe about how I would critique artists, although I may not have the right to do so. Unfortunately, there is now also a trend of marketing the works of artists from the Middle East. Artists from Turkey, Kurdistan, Iran, and Afghanistan often allow themselves to be isolated in a separate bubble.

Many museums and white art spaces that are criticised by some as being too elite, look at us as quotas. They select a few of us, polish them, and put them on the market. When we are unaware of this, we end up competing with each other and trying to pull each other down. We denigrate each other’s work with the ‘copy and paste’ words of some art historians and critics. This is precisely what the white art market wants, while it feeds on hatred, envy, and competition, and that is why we often find ourselves in competition and conflict with each other.

Because of this competition between us, we forget what we should focus on. We also can never say that we admire each other, and when we do say it, it must be to people from our group. We do not have the humility to say, “Well done! You are talented, and you are great.” We constantly try to prove that we are more qualified, and have suffered more and are the best.

When I spend two hours of my life watching a movie, I want to see something extraordinary and take pleasure in saying, ‘I could never have created this, and I never thought about it this way.’ When I go to an exhibition, I want to see something I cannot do, but someone else can. I want to expand my horizons by seeing something remarkable and extraordinary.

People who want to do and be the best at everything, cannot be nourished by anything else around them.

Thank you once again for sharing your time and experiences, Zehra. Hearing about your journey and the resistance both in prison and exile has genuinely moved me. I’m sure I’m not the only one who feels this way. It’s inspiring to realise the potential for action and change. As artists, we’re privileged to have the ability to channel our struggles into our work and art, transforming personal challenges into meaningful expressions. I’ll be keeping an eye out for more of your work and look forward to seeing what you come up with next.

Zehra Doğan

Zehra Doğan is a Kurdish artist and journalist, currently residing in Berlin and continuing to perform and exhibit in various countries.

Maryam Ashrafi

Maryam Ashrafi is an Iranian documentary photographer, photo editor of Turning Point, and the author of the photo book Rising Among Ruins, Dancing amid Bullets.