Cover photo: ©Tim Marrs

It is a humid afternoon in Shanghai, and Lucy, a name we are using to protect her identity, a 25-year-old student of journalism and communication, jumps on her bicycle, fresh out of university classes. Like many young people across China’s sprawling cities, she slips in her earphones before even fastening her helmet. “I just feel like I need a podcast playing all the time,” she thinks. Listening to podcasts can provide comfort, company, and a small space to breath and, for Lucy and millions of people across China, it is part of a typical daily routine.

In 2023, China’s podcast audience surpassed 220 million listeners. The figure has more than doubled over the past five years. More than 60% of these users are aged between 24 and 40, mainly young, highly educated individuals living in first- and second-tier cities. It is also this generation that is driving the production boom: today’s Chinese podcasters are increasingly tackling contemporary cultural and social issues, from gender equality and mental health to technology and personal development.

Like many young listeners across China, Lucy was initially drawn to the world of podcasting as a passive consumer. But after months of tuning in, she began to wonder if she should take the opportunity to become a part of the conversation herself. Motivated by curiosity and a desire to explore social issues more deeply, she teamed up with a friend to launch a podcast of her own. The result was The Question is on the Left, Reality on the Right (《问题在左,现实在右》), a show that reflects the duo’s engagement with critical questions facing contemporary Chinese society.

“Podcasts feel different because they open a space to start asking critical questions and step outside of the reality you were given,” explains Lucy.

For Lucy and many other young creators, podcasting is not about shouting dissent; it’s about nurturing spaces of slow, thoughtful questioning. China has a tightly monitored digital environment. Major platforms like WeChat and Weibo are subject to intense state control. This means people cannot freely express their ideas on regular social media channels. In such an environment, podcasts carve out a rare pocket of freer expression. Contrary to viral videos or public social media posts,podcasts tend to fly under the radar because they’re consumed privately, spread gradually, and rarely spark real-time controversy. This low-profile nature makes them harder to censor and gives space for more honest, in-depth conversations. For a generation craving authenticity, that subtlety can be quietly transformative.

The Boom of Podcasting in China: A Rapidly Expanding Market

China’s podcast industry has grown rapidly in recent years, becoming a dynamic space for storytelling, education, and debate. Projections suggest that by 2027, China is poised to surpass the United States in podcast listener growth, with nearly 179 million listeners. Thisshift signals China’s emerging role as a global leader in the podcasting world.

Three main platforms have been driving China’s podcast boom: Xiaoyuzhou FM (小宇宙), launched in 2020, has become the leading indie podcast app, known for its minimalist design, strong community features, and focus on thoughtful, high-quality content among younger, educated listeners. Himalaya FM (喜马拉雅), one of China’s largest audio platforms, offers a wide range of podcasts and educational content, with a strong emphasis on monetization through subscriptions and premium services. Meanwhile, Lizhi FM (荔枝) pioneers easy, user-generated podcasting and has expanded into social audio experiences to engage a younger creative audience.

Popular podcast genres in China today feature self-help, cultural history, entertainment, and discussions on current events. Increasingly, they are becoming platforms for conversations that push the boundaries of what can be openly discussed under China’s censorship. One standout example is Stochastic Volatility (随机波动), a feminist-themed podcast that has attracted around 600,000 regular listeners by addressing topics such as sexual harassment, women’s rights, and gender inequality. In a society where gender roles remain tightly woven into traditional family expectations and social conformity, this podcast dares to discuss sexual harassment, gender inequality, and women’s rights with honesty and depth — topics often silenced or softened in state-sanctioned mainstream media.

Other voices are also breaking through the static. Bitch-up (婊酱), for instance, brings stories of female sexual autonomy and exploration into the Chinese digital space, drawing inspiration from its roots in the Netherlands. Through frank conversations and imagined narratives, it challenges not only the censorship of desire but also the cultural scripts that frame female sexuality as taboo or deviant. In doing so, it helps listeners, many of whom feel isolated within the rigidity of traditional expectations, to envision new ways of being.Then there’s Youdian Tianyuan (有点田园), which takes on the even riskier terrain of state power and political critique. Beneath its soft-spoken tone lies a sharp interrogation of how gender norms are enforced and maintained through institutions like family, education, and the state. These podcasts don’t shout their resistance — they whisper it, weave it into everyday language and shared vulnerability. And in doing so, they carve out an alternative soundscape where young people can question what they’ve been taught to accept.

How Podcasts Slip Past China’s Rigid Censorship

Grace, a pseudonym used to protect her identity and avoid potential repercussions on her career and personal life, is a young lawyer and podcaster based in Shanghai. For her, podcasting has become more than producing on a certain medium. Alongside four other female lawyers, she co-hosts a show that draws directly from their daily work in courtrooms across the city. Each episode investigates real legal cases involving domestic violence, sexual harassment, custody battles, and workplace discrimination. Grace explains how opinions have a greater chance of being freely expressed via the podcast format “If I posted about gender inequality on Douyin [TikTok], the post would be deleted immediately,” she explains. “But on Xiaoyuzhou FM, using synonyms and a subtler tone, our discussions survive.”

Yet, even in this relatively freer audio space, Grace feels the weight of surveillance. “I have so many thoughts I want to share,” she says quietly, “but I can’t, because I’m afraid.” Her voice, like that of many others, walks a tightrope between truth-telling and self-protection — a reflection of how, in today’s China, even podcasts can be both a refuge and a risk.

Lucy echoes this unease: “Sometimes, I still feel scared,” she admits. “There are moments during recording when I stop and ask myself: ‘Am I supposed to say this?”

Educated in journalism, Lucy says self-censorship has become an internalised skill — something she learned to navigate amongst China’s opaque media rules. Over time, it became almost instinctive: a quiet, constant calculation of what could be said, and how. In her work, she even relies on online tools that compile and update lists of banned keywords, using them to meticulously screen her content before publication. This process, she explains, is not just about avoiding obvious political pitfalls, but about reading between the lines, anticipating what might trigger scrutiny, even when the rules themselves are unwritten or constantly shifting.

The Art of Digital Survival

Aware of the risks, Chinese podcasters have developed an intricate set of tactics to keep their conversations alive. Basically, they play with the language using different literary devices that mask the real meaning behind the word. For example, a certain set of homophones, metaphors, or playful codes are used that seem neutral on the surface but conveys a certain meaning only loyal listeners recognize immediately. Grace explains that over time Chinese netizens have developed a rich vocabulary of coded language to evade censorship.

“It’s like throwing a stone into the water and watching the ripples spread. Maybe you can’t talk about the stone directly, but you can talk about the ripples, and that keeps the conversation going.”

– Zhang Zhiqi

A well-known example is the use of “river crab” (河蟹, héxiè), a homophone for “harmony” (和谐, héxié) — a term often used in official rhetoric to justify content removal. By jokingly saying a post was “eaten by a river crab,” users signal that it was censored, without stating it outright. Similarly, “Uncle Mao” (毛子叔叔, máozi shūshu) is a playful, indirect way to refer to the police, softening the message while still making it clear. This clever wordplay allows critique to slip past algorithmic censors without directly confronting them. Strategic pacing is another tactic to bypass censorship. It refers to alternating lighter, apolitical episodes — such as those focusing on daily life, food, or pop culture — with more sensitive discussions on topics like labor rights, gender issues, or social inequalities, in order to avoid drawing too much attention at once. As Zhang Zhiqi, co-founder of the popular feminist-themed podcast Stochastic Volatility (随机波动), describes it, navigating censorship feels like

“It’s like throwing a stone into the water and watching the ripples spread. Maybe you can’t talk about the stone directly, but you can talk about the ripples, and that keeps the conversation going.”

This kind of stylistic and strategic creativity can boost the chances of content survival but with increasing state surveillance capabilities it remains uncertain whether such tactics are enough to ward off censorship or prevent a show’s removal entirely.

The Elusiveness of Audio

Algorithms can easily scan text or images for banned keywords or visual symbols. But audio content like podcasts pose unique challenges for China’s censorship apparatus. Monitoring spoken content in real time requires highly sophisticated speech recognition systems, and, more crucially, enormous amounts of processing power. Despite significant advances in AI surveillance technology, the sheer volume of audio data generated daily by podcasts, live streams, and voice messages makes comprehensive monitoring a logistical nightmare for state authorities.

This overload of content acts as a temporary buffer. As Samantha Hoffman, an analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, notes, “The collection of voice and video data assists with identifying people, networks, how people speak, what they care about, and what are the trends,” underscores the growing capabilities of voice surveillance, but also the immense complexity and scale involved. In practice, this means that much of what is said in podcasts can still slip through the cracks

That said, regulators are far from idle. Chinese tech companies like iFlytek, a leader in AI voice recognition, are actively building tools to close the gap. In 2017, Human Rights Watch raised concerns about iFlytek’s collaboration with the Ministry of Public Security in developing a national voiceprint database. That is a tool capable of identifying individuals based on their unique vocal signatures. These systems are already being used to monitor public phone conversations and expand state control into the auditory realm.

Analysts warn that increased oversight may be on the horizon, raising questions about how long podcasting will remain a relatively open space. This trend accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when authorities expanded digital surveillance through health codes, location tracking, and facial recognition. Originally justified as public health tools, these systems have since been repurposed for broader social control, making even low-profile media like podcasts more vulnerable to scrutiny.

Yet, for now, audio remains an imperfectly policed frontier — a fragile space where dissent can still echo, if only for a moment. Recent findings from The Citizen Lab, a research group based at the University of Toronto that investigates digital security and human rights, reveal that censorship of Chinese-language podcasts is far less systematic than censorship on traditional social media platforms. Keywords can trigger automatic takedowns within minutes on WeChat or Weibo but podcasting’s long-form nature and slower dissemination patterns often allow content to evade immediate detection.

Social Dynamics: Cultivating Intimate Communities

Apart from a relatively relaxed environment for discussion on sensitive issues, podcasts in China also serve as spaces for the formation of small, close-knit communities. Podcasts allow listeners to connect through thoughtful conversations rather than viral trends.

On mainstream social media, speed and sensationalism dominate. With podcasting, the environment encourages reflection and personal storytelling.

“The personal and conversational tone of podcasts enables creators to discuss complex social issue that we are not usually exposed to,” Lucy tells.

“It’s not about changing the orientation of society (导向), but about opening spaces for meaningful discussion.” she adds.

This emphasis on empathy and dialogue is also central to the vision of Story FM (故事FM) founder Kou Aizhe, one of the pioneers of narrative podcasting in China.

“Through my podcast, I want my audience to understand a human being — their sacrifice, their sadness, their joy. I want them to stand in their shoes and feel what they felt […] In a society so polarised, I believe listening is the first step to understanding,” he explains in an interview with Turning Point Magazine.

Podcasts have also quietly become bridges to the outside world, a role rarely played by the state media apparatus unless it is also loaded with propaganda messages.

As professor Li from the Media and Communication Department at the University of Fudan highlights, “On podcast platforms, you’ll find discussions about gender violence, family tensions, and even political events like the U.S. elections — topics that would be risky or impossible to post about openly on Weibo or Douyin.”

Popular shows like The Unexplainable World (世界莫名其妙物语), and Flip Radio (翻转电台) hold discussions on Western democratic systems, political satire, and the contradictions of globalisation

“Through podcasts, I discovered perspectives that made me want to study abroad. It changed my life,” shares Tristan, a 23-year-old podcaster from Hunan now living overseas. Listening to stories of students thriving abroad and discussions about different education systems opened his eyes to possibilities he had never considered. For many like Tristan, podcasts are not just entertainment — they’re a lifeline to other worlds, and to ways of thinking that might otherwise remain out of reach.

This expanding ecosystem of audio storytelling doesn’t stop at introspection or global awareness — it also nurtures active engagement. Increasingly, shows are experimenting with formats that invite listeners to speak, share, and gather together.

Qiang Qiang Sanrenxing (锵锵三人行) has pioneered the participatory model, hosting live audio forums where listeners join multi-hour discussions on taboo topics such as sexual assault within relationships, the cultural tensions surrounding bride pricing, or evolving gender norms in Chinese families.

These conversations often extend into offline meet-ups and events such as Stochastic Volatility at Duke Kunshan University and PodFest China Annual Conference, an annual conference in Shanghai that brings together podcasters, industry professionals, and listeners to discuss the developments in Chinese podcasting.

In these offline initiatives, podcast hosts and listeners gather for movie screenings, book clubs, or themed salons — a rare form of community-building in China’s increasingly rapid and digitalised urban life.

Additionally, the podcast medium’s very “elitism” — its association with more educated, urban, middle-class audiences — serves as a kind of protection. “Since the audience is limited on platforms like Ximalaya or Lizhi FM, usually composed of educated, middle-class young people, the influence is seen as less dangerous by authorities,” affirms Tristan.

These technical and social dynamics highlight the unique position of podcasts in China’s media landscape. By leveraging both the inherent difficulties of audio surveillance and the power of cultivating close-knit, reflective communities, podcasters have carved out a relatively freer space for nuanced expression — a freedom that is increasingly rare across the broader digital formats in China.

Why Listeners Tune In—and Stay

In a country where public speech is tightly monitored and digital life grows increasingly performative, podcasts offer rare pockets of authenticity—and refuge. For many young Chinese listeners, podcasts are not just entertainment; they have become survival tools in a high-pressure society that demands constant competition, conformity, and silence on sensitive issues.

Hou, a 25-year-old International Communications and Journalism student living in Tianjin, compared podcasts to a digital “book club,” a space where communities form around shared passions—from philosophy and gaming to financial independence. “Podcasts allow me to discover worlds I wouldn’t otherwise know,” he says, recalling how a show about the FIRE movement (Financial Independence, Retire Early) introduced him to global conversations about alternative economic lifestyles—ideas that sharply contrast with the grueling expectations of China’s 996 work culture, where employees are often expected to work from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week. Through podcasts, Hou encountered perspectives on work-life balance, financial autonomy, and critiques of overwork that rarely surface in mainstream Chinese discourse.

Unlike short videos that demand constant attention and rapid reactions, podcasts integrate quietly into daily life—Hou listens for four to five hours a day while biking, cooking, or commuting—allowing new ideas to “seep in” without the pressure to immediately perform or respond. “It’s like being fed new thoughts without feeling overwhelmed,” he added, describing podcasts as a crucial daily source of self-development, reflection, and inspiration.

This sense of intellectual refuge is echoed by Kou, who, having worked in journalism and international media, turned to podcasting to go deeper: “I always wanted to have one program of my own to fully dig into the stories. The story is much, much more than what’s reported.” His podcast, now boasting over 800 episodes, captures the untold emotional landscapes of ordinary Chinese lives.

“It’s a perfect way to tell stories,” he adds, reflecting on podcasting’s advantage over short-form content. “People have a longer tolerance when they’re listening. They can go deeper.”

This depth, combined with intimacy, makes podcasts uniquely suited for today’s social climate. Professor Li, agreed, noting that podcasting fosters “duhua” (对话) — true conversation.

“On podcasts, people dare to talk about gender, politics, and pain — not because it’s easier, but because the format allows for explanation, context, and trust. You hear someone’s voice — their hesitation, their emotions — and you stop judging. You start listening.”, she affirms.

“Unlike Weibo, where it quickly turns into a fight, on podcasts people really talk,” Professor Li explains. “It feels more like mutual understanding is easier to reach — the tone, the voice, the time all help.”

“This sense of community is precious. It’s not like shouting into a void—it’s like a conversation you can join.”

– Yun Ming

A recent publication in the Journal Media, Culture & Society explores that many podcast listeners in China don’t just tune in for entertainment — they see podcasts as a space to slow down and think more deeply. In these audio communities, listeners often feel a quiet bond with the hosts, like being part of an ongoing, personal conversation. This trust creates room for discussing sensitive issues with care and nuance, without the pressure to be loud or confrontational. Platforms like Xiaoyuzhou FM and Bilibili have recognized this growing appetite for authentic interaction, increasingly promoting podcast-like formats where dialogue—comments, discussions, even personal replies from hosts—are encouraged.

“This sense of community is precious,” says Yun Ming, a Chinese Language and Literature student. “It’s not like shouting into a void—it’s like a conversation you can join.”

For Yun, as for many young Chinese listeners, podcasts fulfill a profound emotional and intellectual need. Professor Li highlighted how on Xiaoyuzhou FM and other podcast platforms, comments are much longer than other platforms. “This is because on these platforms people share their own experiences. It’s a sign that people don’t feel heard in daily life — so they turn to podcasts[…]In China, we don’t have rich social lives, especially in big cities. You work, you go home. Many live alone or with strangers. Podcasts become these substitute conversations we’re missing.”, she explains.

According to a 2023 survey by Daxue Consulting, over 70% of Chinese podcast users cite a desire for “belonging and emotional connection” as a primary reason for listening—a stark contrast to the performative culture that dominates most mainstream social platforms.

“While cooking alone, I would listen to podcasts—it made me feel awake, connected to bigger worlds beyond my everyday,” Yun adds. In a society where silence often feels heavy with unspoken rules and suppressed emotions, simply hearing human voices—thoughtful, vulnerable, questioning — becomes quietly powerful. This helps explain why, for many like Lucy, Hou, and Yun, podcasting has become a daily lifeline.

The Uncertain Future of Podcasting in China

Despite podcasting’s relative freedom compared to other digital media, the breathing space is shrinking. Platforms like Xiaoyuzhou FM, once celebrated for their open atmosphere, have increasingly tightened content moderation policies. In 2023, they introduced new community guidelines that restrict politically sensitive discussions and enforce real-name verification for podcasters.

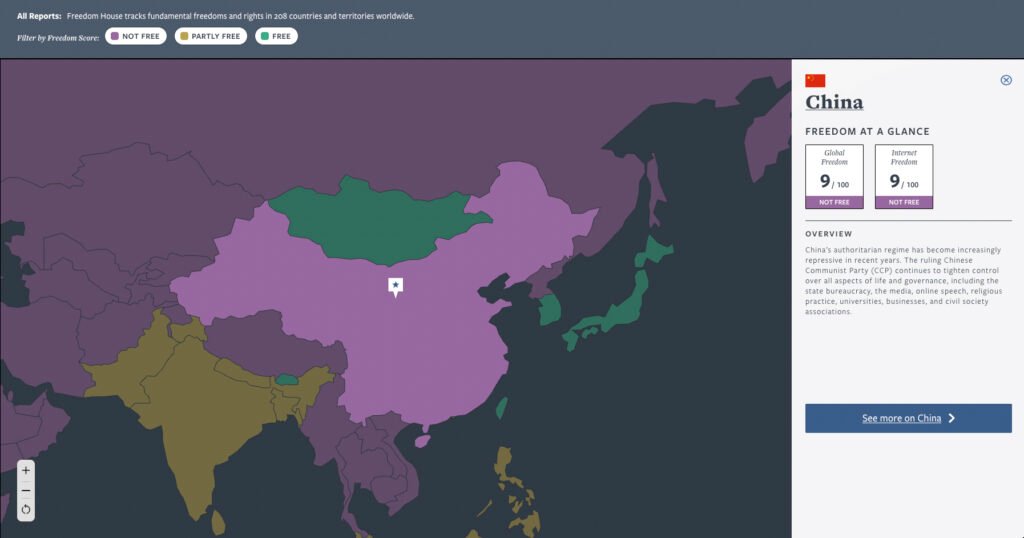

As podcaster and daily listener Tristan put it, “I am not too optimistic about the future of podcasts in China because the more they become followed by people, the more they will be subjected to state censorship like any other social media.” Analysts at Freedom House echo these fears, warning that as independent audio platforms expand their reach, authorities may soon apply the same stringent surveillance and censorship tactics already targeting text and video content.

Even amid growing restrictions, podcasting in China remains a rare middle ground — an intimate, subtle medium where freedom of thought still flows quietly through millions of headphones. Its strength lies in its nuance — but that’s also what makes it fragile.

In Shanghai’s winding lanes, Lucy rides her bike with a podcast in her ears — a small act of connection and quiet resistance. “It’s not like I believe podcasting will change the whole country,” she says, smiling, “but maybe we can open up a few more possibilities in people’s lives — help them imagine something better.”

In a fast-changing society, podcasts have carved out uncommon spaces for reflection and conversation. Each episode subtly challenges official narratives, offering listeners a sense of solidarity and a glimpse of a future shaped not by silence, but by shared understanding.

Gaia Guatri

Gaia Guatri is an independent photojournalist and documentarian specializing in gender inequality, migration, and social justice, with a background in anthropology and international relations. She reports across Europe, China, and Southeast Asia. She collaborates with global media outlets like The Copenhagen Post, Weave News, and Pangyao Magazine to amplify local voices and bring human-centred stories to international audiences.

Shekufe Ranjbar

Shekufe Ranjbar is a multimedia journalist and researcher. She writes about culture and society. Her research is focused on journalism in repressive contexts.