Cover photo: A billboard advertisement about the campaign against fentanyl is seen in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico, on February 5, 2025. ©Felix Marquez

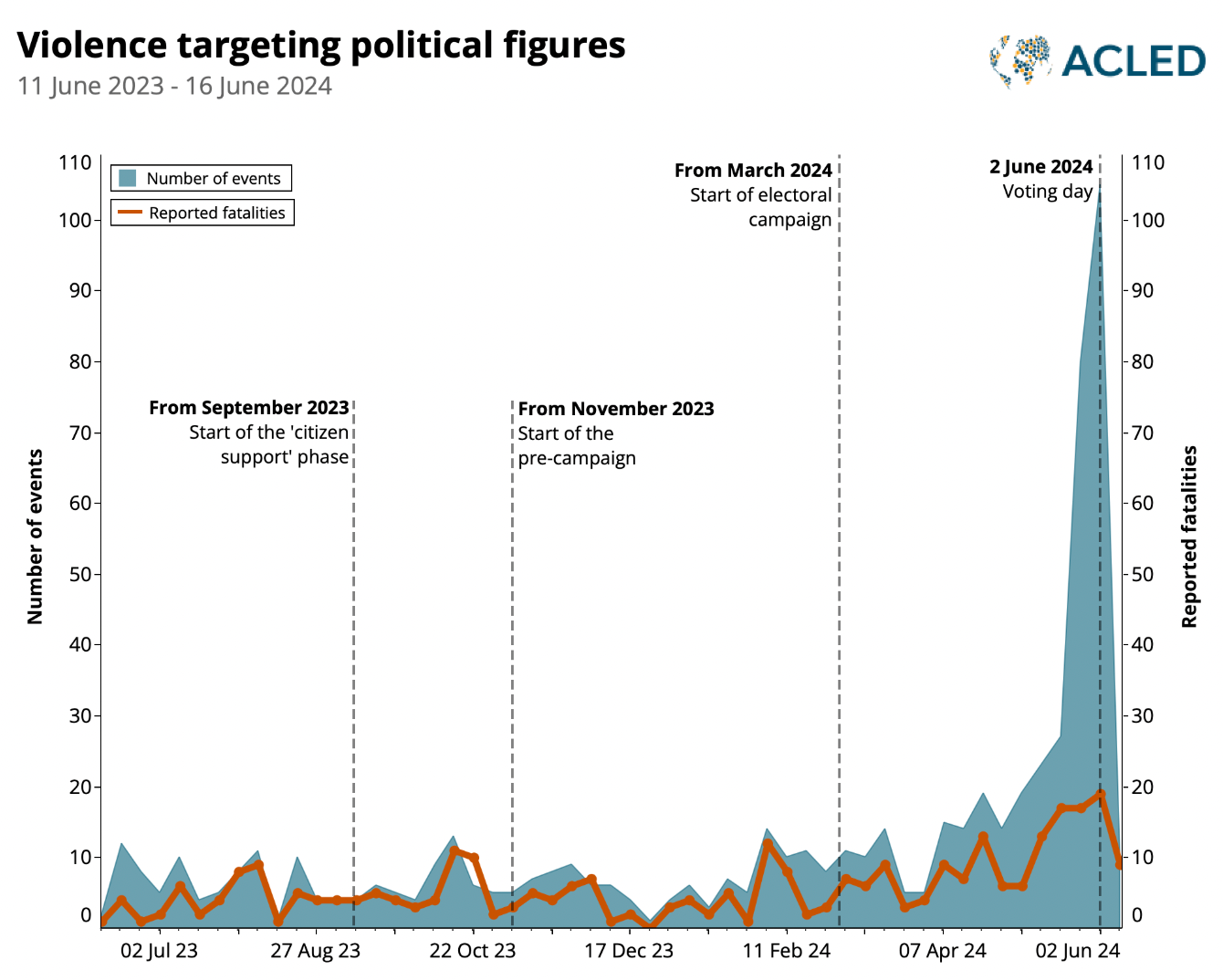

On May 27, 2024, Pedro Salazar Rodríguez and four other members of the opposition party Movimiento Ciudadano—all candidates in the local elections in the state of Tamaulipas, Mexico—were attacked with firearms while traveling on the Victoria-Matamoros highway. Armed civilians approached their vehicle and opened fire. Fortunately, they survived. However, this is not always the case in Mexico. The following day, Salazar Rodríguez appeared in the main town square for the closing event of his campaign. Despite the fact that during the campaign leading up to the June 2024 presidential and local elections, at least 38 candidates were killed, Salazar Rodríguez chose to run anyway. He did not become mayor of Jiménez, but he did not withdraw from the electoral race either, which is not a given. It does not always happen this way with structural violence in the country making everyday life, especially political engagement, dangerous and cumbersome.

Violence in Mexico is a daily occurrence. Since 2006, with the beginning of the so-called war on drugs, it has exploded. There is an undeclared war and campaign of intimidation against politicians, those who oppose speculation, and those who denounce corruption, violence, and special interests. Since 2006, there have been at least 400,000 deaths and 100,000 forced disappearances and abductions. Political elections are typically the high point of tensions in the country, and they are influenced by power dynamics that sometimes involve murder.

On June 1, Mexico voted for the direct election of judges and magistrates. It became the first country in the world to determine all judicial positions, from local courts to the Supreme Court, through elections. This reform, initiated by former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and presently defended by current President Claudia Sheinbaum, has faced criticism. Like all powers in Mexico, the judiciary is also affected by corruption and power dynamics, so reform is doubtlessly needed. But many wonder if this will allow legal and illegal power groups to influence the vote and, consequently, decide who will judge crimes in the country.

If corruption dominates in Mexico, how can we prevent corruptive logic from entering the electoral mechanism for judges? For example, Francisco Herrera Franco ran for a federal judge. However, several human rights groups have pointed out that the former regional prosecutor of Michoacán has been accused of alleged ties to criminal groups and involvement in the murders of journalists Roberto Toledo and Armando Linares from the Monitor Michoacán portal.

Only 12% of the population voted. While there were no “scandalous elections,” most candidates were close to the ruling party. Others were aligned with formations launched by judges. Many wonder why the elections for judicial power were conducted so smoothly in contrast to local elections.

The security situation around electoral violence has reached a boiling point: in the first quarter of 2025 alone, there were 104 incidents of violence against politicians. According to Integralia’s report on political violence, this number represents a 59% increase when compared to the number of incidents during the same period of 2024.

Since April, Veracruz, in southern Mexico, has become the epicenter of political violence. Due to threats and violent incidents, 54 mayoral candidates have requested security measures. Marisol Alicia Delgadillo Morales, president of the local public electoral body (OPLE), reported that protection measures are being provided to those who request them, with support from the State Public Security Secretariat. Yesenia Lara Gutiérrez, a candidate for mayor of Texistepec from Morena (the president’s party), was killed while live-streaming on Facebook and walking through the city during a campaign event. Two days earlier, Esteban Alfonseca Salazar, former mayor of Actopan, a municipality in central Veracruz, was shot and killed on the Santa Rosa-Actopan highway, along with former councilor Edmundo Martínez Pérez.

It is not just candidates who are killed and threatened. In Mexico, the murder of Ximena Guzmán, the private secretary of Mexico City Mayor Clara Brugada, and her adviser José Muñoz, on the morning of Tuesday, May 20, 2025, shocked the nation. They were attacked and killed on one of the main avenues in the capital, Calzada de Tlalpan, by individuals on a motorcycle.

No one is safe. On May 30, a concert by Fermin Muguruza at the Multiforo Alicia was raided by the army, National Guard, and police with weapons drawn. To this day, no one knows who ordered the action and no one has taken responsibility. Politics distances itself and points fingers at the police. However, the police do not have the authority to call in the army. The police are also under scrutiny for the murders of Pepe and Ximena. Though it can be difficult to separate fact from rumor, it is evident that there is a struggle for control of the city and the country, a struggle that may involve the ruling party but certainly sees the armed forces as an active player.

The battle for territorial control, driven by power currents linking together politics, and legal and illegal economies, shows no mercy. But even more than politicians and candidates, activists, journalists, and human rights defenders are focal points of violence. There are stories that have made headlines worldwide, like the disappearance and murder of students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Normal School in 2014, or that of Samir Flores in Morelos – the land of Emiliano Zapata. But then there are cases like Marco Antonio Suastegui or Javier Valdez, which remained at the local or national level but described a consolidated dynamic. Javier Valdez, killed on May 15, 2017, in Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa state in northern Mexico, was a journalist and investigator who repeatedly exposed the interconnections between politics, power, economic interests, and organized crime. He was the first to reveal how the criminal world was a way of life. In his 2007 book Miss Narco, he wrote, “The narco is everything. The narco is not just violence, police and military against criminals. The omnipresent and omnipotent narco is, like God. The everyday narco: every neighbor, workshop, mechanic, relative or friend, lover or colleague, fellow driver, diner, and hairdresser is involved: the narco is a way of life.”

In a 2016 interview with La Jornada, Valdez said, “We’re not just talking about drug trafficking, one of our most insidious traps. We’re also talking about how the government sets us up. How we live in a newsroom infiltrated by narcos, next to a colleague you can’t trust because maybe they pass information to the government or to criminals.” He added, “We also point out the businessmen, the bosses, and the media executives who prioritize business, who are more concerned with profit than telling the story of what’s happening in our country or what might happen to their reporters, their employees.”

It is not easy to find someone willing to speak openly on the subject. It is especially difficult to go beyond the easy, polite, and approved narrative that it is the criminal groups and their thirst for power that drive all the violence. Memory is often short, so we can easily forget that investigations into the Ayotzinapa case have highlighted the responsibilities of the Prosecutor’s Office, the army, and other police forces in the aggression against the young people who were disappeared and then killed. There was also a decision to create false evidence about their fate. We forget that 90% of murders in the country go unpunished and that there are no adequate investigations to identify perpetrators, principals, and motives. We forget that the army played a decisive role in the massacre of 72 migrants in San Fernando, Tamaulipas. We forget that Germán Reyes Reyes, a former military officer and head of the municipal public security department in Chilpancingo, was accused of the murder of the mayor of Chilpancingo in Guerrero. We forget that army personnel shot and killed six migrants in Chiapas. We forget that 23 police officers were arrested and accused of the murder of a mayoral candidate in Michoacán. We have forgotten the Tlatlaya massacre, where at least 22 people were arbitrarily executed by the military in the State of Mexico. In short, we forget many things and do not look at how often coercive and co-interested relationships are created between criminal groups, large corporations, and politics.

One source, who wished to remain anonymous, told me, “Look closely. In the last 19 years, how many criminal conflict zones in Mexico were affected by large infrastructure projects halted by social struggles. And look, after 19 years, how many of those projects were eventually carried out, and how criminal violence created a situation favorable for their realization.” And perhaps it is no coincidence that just on April 23, presenting the report “Land for those who work and defend it. Ten years of aggression against women defending land, territory, and natural resources in Mesoamerica (2012-2024),” the organization Iniciativa Mesoamericana de Mujeres Defensoras de Derechos Humanos (IM-Defensoras) indicated that in Mexico, from 2022 to 2024, during the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, “860 aggressions against activists defending the territory who confronted large economic interests behind extractive or infrastructure projects” were documented.

In short, the issue is complex, not homogeneous, and changes from region to region, but has one constant: control of the territory for speculation. State and criminal violence in Mexico creates territorial governance, redraws boundaries and controls, fragments, and redistributes. It is a manifestation of authority that involves economic, political, military, and communication powers. It is one of the models used to ensure the reproducibility of a system that speculates on lives and protects privileges and social inequality. And precisely because of this, the triangulation of politics, legal and illegal economies, is capable of making agreements, forming alliances, and networks, feeding itself and using all tools, legal or not, to ensure an advantage over competing groups. Many know this and openly say it. Many do not trust politics because they know it is part of this undeclared war. Many are afraid to say it and prefer to remain silent. From academia to the press, from politics to associations, violence is often internalized, and to avoid becoming victims, it is preferable to talk about something else. And then there is high politics, starting with President Claudia Sheinbaum, who tries to downplay the problem, effectively accepting it, silencing it, and normalizing it, becoming part of the problem.

In this Mexico where corruption has wiped out trust, where people die for a few pesos, and where the interests generated by control of the territory fuel an undeclared war that frightens people, the story of Pedro Salazar Rodríguez should have made history. He won, symbolically, by running for office until the end, not succumbing to the fear, and being still alive. But nothing more is known about him. He broke his silence on social media on April 30, after a full year of total silence, even on Facebook. He wished everyone a happy Children’s Day, and nothing more. The news no longer mentioned him, and he no longer sought visibility.

Andrea Cegna

Journalist born in 1982. Currently a contributor to several Italian newspapers including Il Manifesto, Radio Onda d’Urto, Radio Popolare, Altreconomia, Il Fatto Quotidiano, Desinformemonos. Cegna started by conducting programs at Radio Lupo Solitario, in the province of Varese. He has also written books, the latest “What Happens in the City” for Prospero Editore. He also makes podcasts and documentaries. He tries to look at the world critically, trying to free himself from the colonialist forms with which we are used, in the West.