© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, January, 2020.

After more than a year in a hotel, the tenants of this building on rue Saint Pierre were briefly allowed back into their flats to collect their belongings. The municipal services had come to open the building’s padlock, but it wasn’t enough: they discovered that their accommodation had been squatted and ransacked while they were being evicted. Virginie holds a tiny, desperately empty box in her hand: “My God, inside it was… it was my son’s first baby tooth. It’s lost.”

© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, July, 2019.

Evacuation of several flats in rue Curiol: residents take their belongings out of their flats, which are about to be closed. Those evicted described the experience as deeply traumatic; emptying your flat in less than an hour, not being given any advance warning, not knowing where you’ll be sleeping that evening, and even less where you’ll be able to store your personal belongings.

© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, March, 2019.

Marie poses in front of her building, located in the Ventre neighbourhood in the city centre. She was evacuated three months ago with her partner and two young children because two buildings adjacent to hers were demolished by the city council. Marie: “Your home is where you let go and can be yourself. Not being in your home means not being able to let go. It also means losing your daily routine: everything that makes life easier day to day.”

© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, July, 2024.

Amidou is trying to rid his bedroom and mattress of bedbugs in a squat in the 15th arrondissement of Marseille (rue Cougit).

© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, March, 2019.

Thomas, evicted from Cours Lieutaud, once lived in a flat-share across from the buildings that collapsed: “From my window, I could see these people on their balconies, smoking or chatting. From one day to the next, these people disappeared. And for weeks, days and nights, there was the awful sound of the caterpillar digging up the rubble. I can still hear it.”

© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, February, 2019.

On February 2, hundreds of demonstrators marched to Marseille town hall to denounce poor housing, substandard buildings, and the town hall’s wait-and-see attitude.

© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, March, 2019.

Chaima, in shock, in the kitchen of her flat on Avenue de la Capelette. “I don’t want to come back here, it’s too dangerous. It’s criminal to let people live here, they want us to die? No one is helping me, so I’ve started a hunger strike.” The Town Hall has just lifted the danger order on her building. The managing agent says that work has been carried out, but the building itself is in an extremely poor state of repair. Last December, a piece of the roof fell into her kitchen, almost crushing her and her two children. Nothing has been repaired since. Her rent was 600 euros for around 30m2.

© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, March, 2019.

Baya, 68, in the 8m2 hotel room she has occupied since being evicted a year and a half ago: “I live here without access to my flat, which no longer looks like anything: first it was burgled and everything was taken. Then the workmen jackhammered through what was left, amidst the clothes and belongings. In the meantime, I’m continuing to work because retiring wouldn’t be enough for me to live on.”

© Anthony Micallef

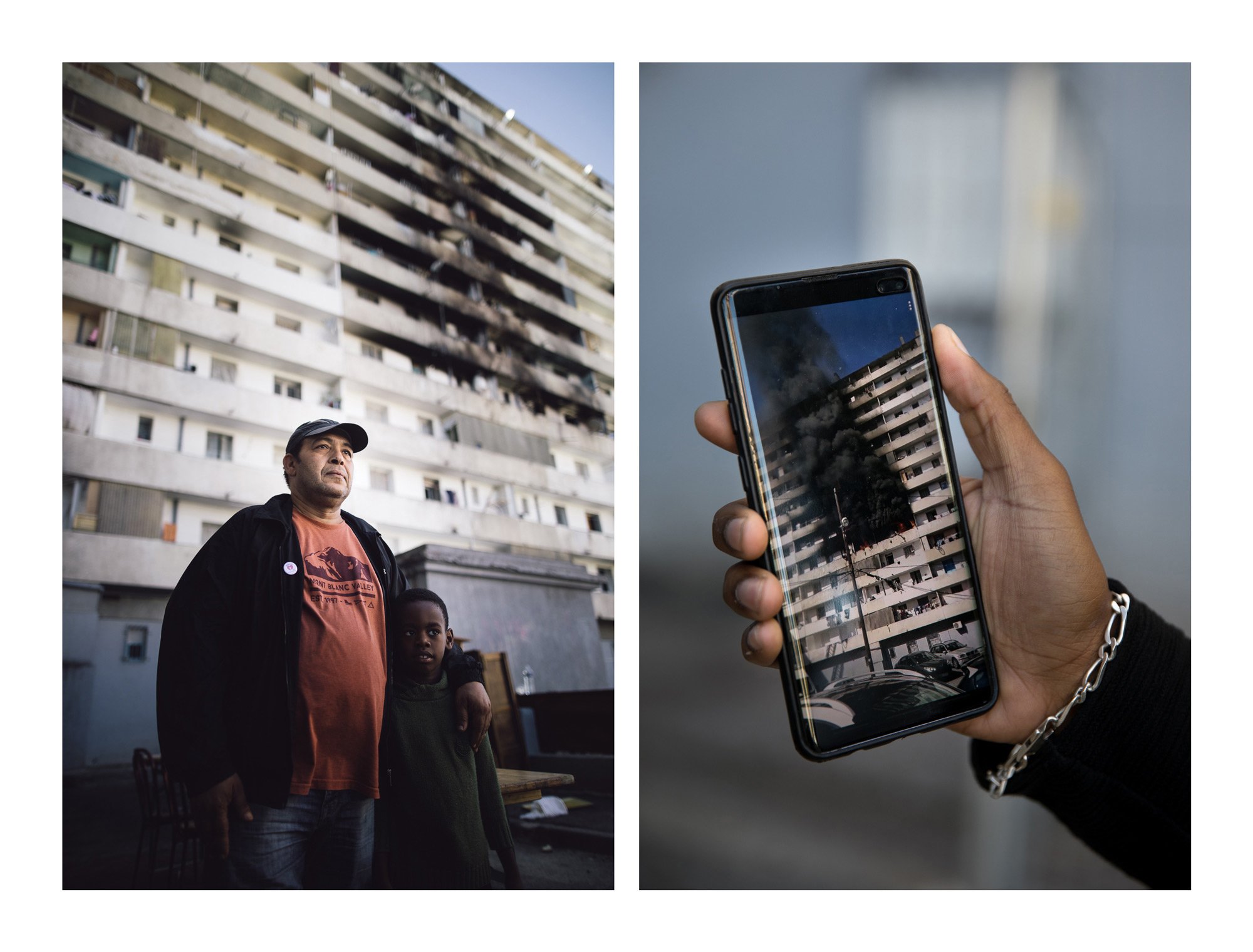

France, Marseille, March, 2019.

Mohamed, A volunteer from the 5 November Collective, visits the Maison-Blanche housing estate, where a fire destroyed several flats in the summer of 2019. The housing estate is in such a poor state that it is one of France’s 17 ‘national priorities’. “I got involved because I can’t stand the contempt shown by the town council towards the poor in this town. They’re treated like second-class citizens. But if I do so much, it’s also because it fixes me,” says Mohamed.

© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, September, 2023.

Steps too big for them. It’s the start of the new school year at the Collège Jacques Prévert, which is bursting at the seams with 600 pupils, the vast majority of whom are experiencing serious difficulties both academically and socially. Classified as a priority education school, it is located in the heart of the Frais-Vallon housing estate in the northern suburbs of Marseille.

© Anthony Micallef

France, Marseille, July, 2024.

Stefan and Fanka, residents of a squat for Roma people from Bulgaria in Marseille’s 3rd arrondissement (rue Félix Pyat).