© Sophie le Roux

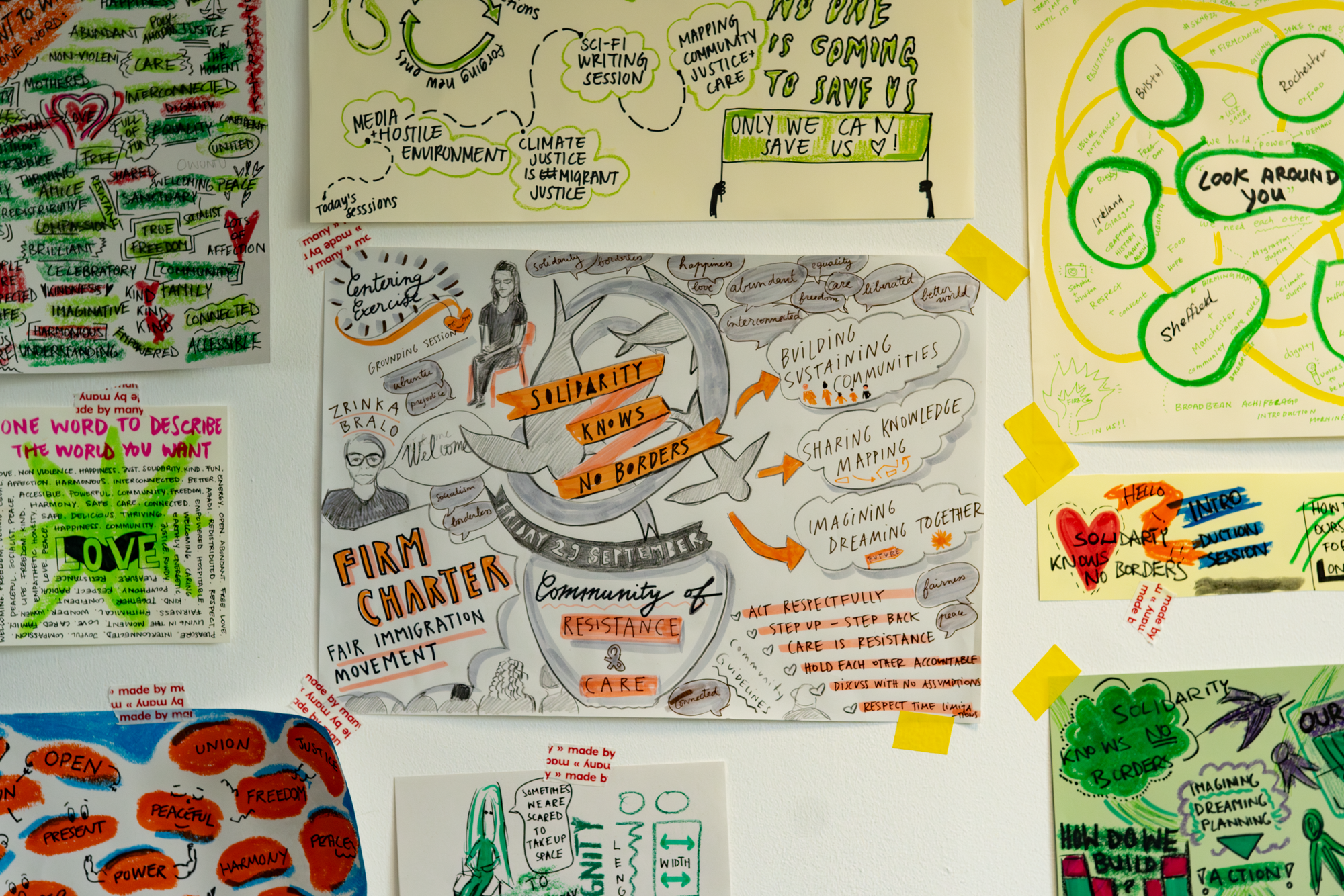

October 28-29, 2023, London, United Kingdom.

Hand-drawn strategy maps from the Solidarity Knows No Borders National Summit 2023.

People on the Move in the 21st Century: Deliberately Silenced and Preferably Unheard

December 31, 2025

On 1 October 2025, a Sunday Times headline caught my attention:

“Cleaner who secretly worked 17-hour days sacked from parliament.”

Mulikat Ogumodede had spent sixteen years cleaning the Palace of Westminster by night and Deutsche Bank by day. Seventeen hours a day. Five days a week. She had a good record. She said she felt “very well” and rested on weekends. But none of that mattered. The agency insisted she had breached working-time rules. She was dismissed. The report states that “mother was accused of ‘deliberately’ failing to inform bosses that she had two jobs.”

When I shared the story with friends, we joked about “hard-working” immigrants stealing two British jobs at once. We laughed. Then I stopped. We don’t actually know if Mulikat is an immigrant. Most people will assume she is, because of her name, which is a shortcut for “other.”

The Times article is an example of the mainstream’s avoidance of asking the only question that matters: Why does a mother fight so hard to keep two minimum-wage jobs totalling seventeen hours a day? How many extra years has she worked? And how much of her life has she lost scrubbing the corridors of power instead of being with her children? What happened in 2008 that made it hard for people to survive on one minimum wage job? Who has made a profit from her labour?

It is safe to assume that these cleaning jobs are minimum wage jobs, and that she has been lawfully employed. However, one thing that no one wants to face, not the employer, the judge, or the journalist, is the fact that, as a working person, Mulikat cannot survive on just one job. And that makes her, regardless of where she is from, exactly the same as tens of millions of other members of the British precariat. Delving deeper into the systemic problem of outsourcing, cleaners are hardly ever employed by the places they clean. Their wages are lower because an agency profits on the backs of people like Mulikat.

Mulikat’s story isn’t an outlier. It is an X-ray of the Britain we live in, where the humanity of working people is erased long before a headline makes them visible—and only if there is a way to portray them as deviant, unbelonging “other,” albeit with an impeccable record in both jobs.

1998, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Personal archive photo of Zrinka Bralo.

Our Stories Don’t Lie. Systems Do

Mulikat’s story is not new to me; I have seen a version of it all my life: people blamed for working hard, punished for surviving and stripped of context.

I would liketo believe that it is my critical thinking, sharpened through the journalism I did early in life, but it is more likely that I recognise this reality because of where I come from and what shaped me.

Like Mulikat, I have one of those foreign-sounding names that makes it hard for people to resist the “Where are you (really) from?” question.

The question they are really asking is: ”Why are you here?”

I am often tempted to share Ambalavaner Sivanandan’s well-known aphorism: “we are here because you were there.” It captures with simple elegance the irrefutable relationship between imperialism, neoliberal capitalism and the forced movement of people due to war, poverty, climate, or all of them intersecting.

My preferred answer these days is that I’m “from the 1980s.” It makes people laugh, sometimes nervously, but at least we can move the conversation along, disrupting the movement away from the identities of borders, into something more interesting, and something we can relate to—the identity that is forged in travel through time.

I grew up in a country that no longer exists, but I only recently stopped referring to it as the “former” Yugoslavia. My childhood, happy, safe, ordinary to the rest of the world and extraordinary to me, was in Sarajevo, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, one of the Yugoslav Republics. I danced in the opening ceremony of the 1984 Winter Olympics. My generation experienced something rare: a childhood untouched by extreme inequality. We inherited a history of resisting empire. I grew up around the corner where Gavrilo Princip, a 19-year-old member of the anti-imperialist Young Bosnia movement, fired a shot at the Archduke Franz Ferdinand that ignited WW1. Communist partisans led by Tito carried out the socialist revolution while kicking the Nazis out in WW2. Tito went on to establish the Non-Aligned Movement, which helped maintain the fragile balance between the two Cold War blocs.

Then came the 1990s. Nationalists fed on the economic crisis until the country tore itself apart. I lived through the siege of Sarajevo, through genocide, through the dissolution of everything I understood as home and that belonged to me. My family joined the endless line of people moving not because they wanted to, but because they would die if they stayed.

The war and genocide erased the wisdom and joy of our histories and in the public narrative reduced us to exile, physically, historically and emotionally.

That experience led me into three decades of work on the frontline for migrant justice and trained my perception. It made me suspicious of simple stories. It made me insist on context. It made me shout about the fact that people do not flee because of “pull factors” but because of wars, famines, foreign interventions, collapsed economies, climate disasters, and political greed. And it taught me that dehumanisation always starts quietly, long before the violence becomes visible.

Mulikat’s story, and the stories of people seeking protection today, sound painfully familiar. I recognise the erasure. I recognise the scapegoating. I recognise the way people become symbols of fear instead of being appreciated as resilient neighbours. If you are one of the “others” you do not get to have a story.

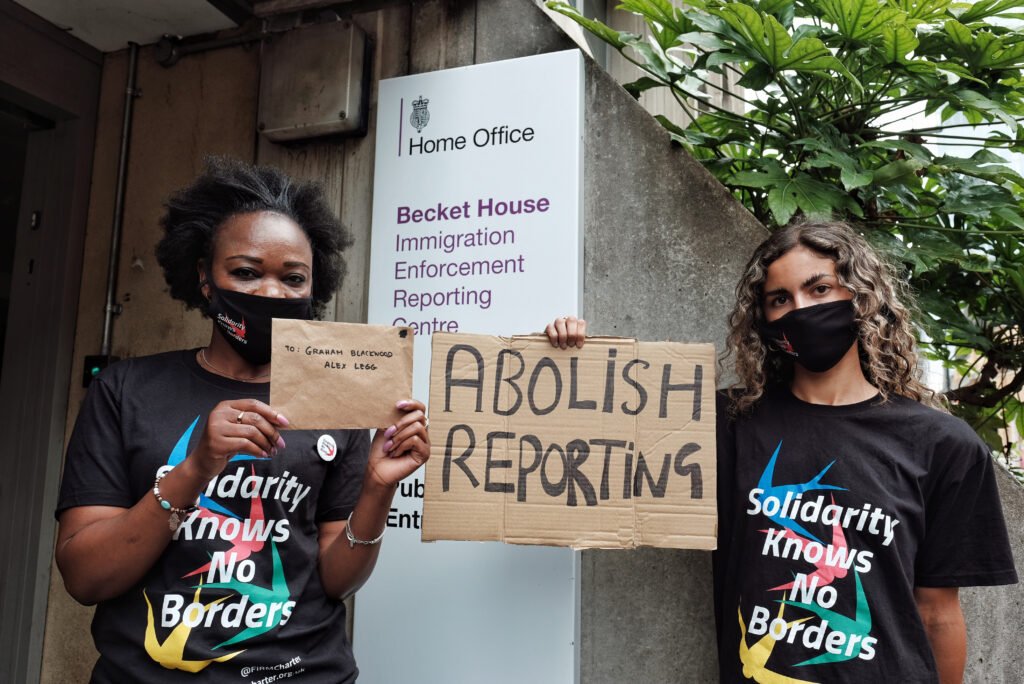

© protests_photos

August 20, 2021, London, United Kingdom.

Organizers from Migrants Organise outside Becket House. The #AbolishReporting campaign highlights how mandatory in-person reporting is an unnecessary form of control that causes “massively reduced stress” when removed. This action demands an end to the “hostile environment” and racist enforcement tactics.

Hostile Environment: Not a Failure of the System – It is a System.

Britain’s immigration debate has always needed a villain. In this myth, migrants and refugees take houses, take jobs, take benefits, destroy the National Health Service, and eat the swans. And when all else fails, steal too many jobs, try to learn English, and integrate! The script is recycled, the actors change, and the truth and facts are erased. And like in the case of the Windrush Scandal, there is no statute of limitations: belonging is not up to you, and what happens to you can change at any time—just ask the Windrush generation and EU citizens in the UK.

The latest, currently unfolding chapter is the so-called “migrant hotel crisis,” a manufactured outrage built on the pretence that these buildings, where refugees are forced to stay, are functioning hotels rather than for-profit semi-detention warehouses run by private contractors. In this story, people seeking sanctuary are cast as “illegal” and “young men of fighting age.” They are variously blamed for veterans’ homelessness, a threat to women’s safety, and the fragility of public services.

As I write, just after yet another hostile, racist immigration policy has been announced by the government, four mothers who had signed up for an English class at their children’s Dalmarnock Primary School in Glasgow, were picketed by a crowd of protesters outside the school gates with signs such as “protect our kids,” “kids before council convenience” and “No checks? No access”. Far-right social media influencers, a right-wing podcaster and supporter of Tommy Robinson, claimed it was “absolutely bonkers” to hold English classes at the school and said it was “all a bit smelly.” There is no evidence that any of the four mothers attending the classes posed any threat.

The protest disrupted schooling. Most children stayed away, and those who remained were forced to stay indoors during their morning break.

None of it withstands scrutiny. But the point is not truth, it is permission. Permission to treat certain groups as a threat and as disposable. Permission to turn racism into common sense, even when it makes no sense. Permission to forget the world that existed before the hostile environment, because forgetting is the objective for the normalisation of harm.

Meanwhile, the far right mobilises with ease. Grievances circulate in local social media groups, metastasise into talking points, and spill onto the streets, as we saw at the Uniting the Kingdom march in September 2025. Disinformation is no longer fringe; it is mainstream infrastructure. And it is a very well-funded infrastructure.

For instance, small-boat crossings are a manufactured problem while they account for only a minority share of arrivals. Their political salience outstrips their statistical weight in the light of our “fair share” of offering protection to 0.09% of people forced to flee.

When people started arriving on boats? Is the question that is never asked and therefore never answered. And without it, we never get to the question of why. And how did they come before? Because that rabbit hole of “why” questions would expose the deep hypocrisy of the invisible doctrine of neoliberalism.

“The dominant ideology of our times—that affects nearly every aspect of our lives—for most of us has no name. If you mention it, people are likely either to tune out, or to respond with a bewildered shrug: ‘What do you mean? What’s that?’ Even those who have heard the word struggle to define it.”

Follow the Money

There is a line from the cult series The Wire that I often think of: “You follow drugs, you get drug dealers. But you start to follow the money, and you don’t know where the f*** it’s gonna take you”.

And like with my time travel in relation to where I am really from (the 80’s), the money needs to be followed through time too in order to make sense of how we got here.

Neoliberalism—powerfully branded “the invisible doctrine” by George Monbiot in his new book—shapes the world while pretending to be natural law. It dissolves borders for capital while fortifying them against people. It destabilises economies, extracts resources, and manufactures the crises that later become the “problem of too much immigration.”

Now conveniently erased from this story is how empires drew borders and carved lands for profit, their people erased and subjugated by violent military force and racism, and left to reckon with the fractures that the empires designed.

The imperial world wars take up a large part of the historical narrative, but the world has been at war over the dominance of resources every single day since 1945.

Since 1992, forty-five wars have erupted. Most had foreign or proxy involvement. Climate change has contributed to at least fifteen conflicts.

It is almost impossible to trace how much money has been made in these wars. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) tracks the top 100 global arms-producing and military services companies. For context, in 2023 alone, their combined arms-related sales reached 632 billion US dollars. The majority of those firms are based in the United States (about 57 % of the top-100 firms), and a significant portion are in Western Europe.

The number of people displaced by these wars has risen from 19 million in 1992 to 123 million today. Britain’s applications for asylum, although higher than before, amount to just 0.09% of the global total.

The scale of displacement is global. The panic is local. And entirely manufactured.

The crisis is in how out of control the neoliberal greed is in the asylum system. Follow the money, and you will find private companies earning millions to house asylum seekers in unsafe hotels. Follow the money, and you will find the arms manufacturers thriving on war and instability in places from which people are escaping. And, now, let us forget the profit tech conglomerates are raking in while harvesting data and shaping public anger.

The “asylum hotel crisis” is not a failure. It is a supply chain. Rwanda flights, floating prison barges, and PR stunts burn public money while fuelling far-right narratives. Everything works as intended, just not for the public.

In reality, small-boat crossings in the UK are not a crisis. The crisis is what forces people into boats in the first place, and what we choose to ignore in the pursuit of political convenience.

The crisis is that 172,420 dependent children, just in England, are living in temporary accommodation, often overcrowded, full of mold and with no basic facilities for cooking or laundry. The crisis is that the Trussell Trust reported that its network of food banks distributed about 2.9 million emergency food parcels in the year to March 2025, and over 1 million of those parcels went to children.

These stories are never linked, and even with all the tools available nowadays, it is still very difficult to follow the money and expose the relationship between the profit, racism and universal human experience of poverty and exploitation that shows how much more we all have in common.

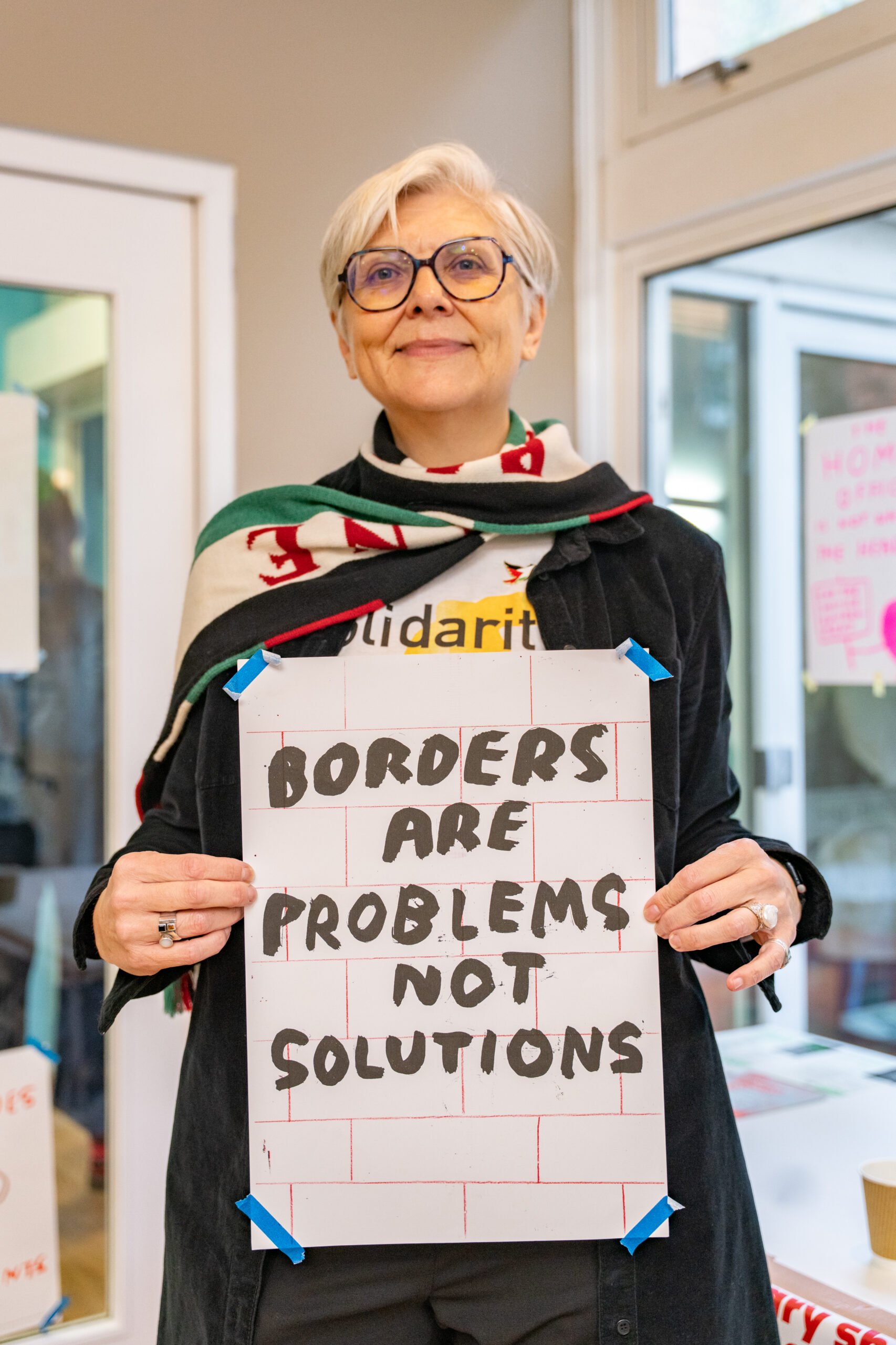

© Sophie le Roux

October 11-12, 2025, London, United Kingdom.

Solidarity Knows No Borders Summit 2025.

Solidarity, Not Charity

And yet, against all this erasure, against the hostile and racist systems, against the manufactured crises and the profitable chaos, another infrastructure has grown. Not sanctioned, not resourced, not invited. Built by migrants, for migrants, and with the clarity that comes only from experience of living at the sharp end of these policies.

Over three decades at Migrants Organise, we have been stitching together an organising tradition rooted in a demand for dignity, justice and freedom. It began as survival work, helping people navigate a system that was deliberately designed to break them. But survival is never enough. When the system is built on cruelty, fighting it alone becomes a conveyor belt of despair.

So we shifted from a charity logic to a solidarity movement logic: we need power to change the rules, and not beg for exceptions.

Today, across the country, that logic has become a living infrastructure. Migrants Organise and our allies have built networks of collectives, campaigns, grassroots groups and rapid-response teams. Under the banner of Solidarity Knows No Borders, communities defend each other in ways the state refuses to.

When the far right mobilises outside so-called hotels, it is often migrant organisers, alongside local neighbours, who stand between vulnerable residents and violent intimidation. When raids threaten families, it is rapid-response groups who show up first. When policies shift overnight, it is grassroots organisers who translate, explain, de-escalate, and rebuild trust and power to get up and start again.

This is not glamorous work. It is slow, stubborn, and often heartbreaking. But it builds power from the ground up, not as a slogan but as a muscle, a practice that grows stronger each time people refuse to be divided into deserving and undeserving, legal and illegal, useful and disposable.

My own journey through war, exile, journalism, and decades of organising has taught me that solidarity and hope are not feelings. These are methods that require discipline to put into practice. We fight back not because we are activists by nature but because we know, intimately, what happens when no one does.

We refuse to forget that people on the move have always been the first to sense when the foundations around us are cracking. And as cracks are showing all around us we have no choice but to organise.

The Future Will Be Organised

The populist right reads feelings well. In Bosnia in the 90s, and the US and the UK now. It translates economic insecurity and civic neglect into an ethnic story: who belongs, who doesn’t, who’s to blame. It doesn’t need facts; it needs a folk narrative. Over the last few decades, this narrative has been reinforced by a policy that Theresa May proudly dubbed “the hostile environment policy,” which is now completely normalisedto the extent that the memory of what it was like before has been completely erased.

The real crisis is not migration. It is whether we allow fear, misinformation, and dehumanisation to shape the future. People on the move are the canaries in the coal mine. Ignore them, and the collapse that follows will not spare anyone.

Migration is not a problem to be solved. It is the truth about who we are. People have always moved. They will continue to move, especially as climate collapse accelerates. And they will continue to move because that’s what we as a human species do.

The question is not whether migration will define the next century. It will. The only question is: what kind of world do we want to build in response?

We can sit still paralysed in fear, or we can organise from the ground up in solidarity with each other, building trust and communities one conversation and one action at a time.

Learning from our past and our present, we must not forget that the future is not fixed.

The transformative organising doesn’t wait for friendlier headlines. It builds them by changing the facts on the ground: community defence against the far-right, against landlord harassment; rapid-response teams when hotels are targeted; testimony that reframes who is at risk and who keeps Britain running. It’s slow, stubborn work, but it inoculates communities where misinformation would otherwise spread unopposed.

If you want to puncture the scapegoating, you have to change the story and the storyteller. That means media that report with context, proportion and consequence, not spectacle; politics that levels with people about labour markets, public services, and revenue; and movements that insist migrants are political subjects, not props—organising with power, not pleading for pity.

Because the real “existential crisis” isn’t migration. It’s whether we’ll keep mistaking a manufactured panic for common sense and keep letting the people who profit from fear write the script.

David Graeber famously said: “The ultimate, hidden truth of the world, is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently”.

For the sake of our future, our political spaces now must not be abandoned and surrendered to the far right. What needs doing now is to organise and fight for dignity, justice and freedom, as if life depended on it, because it does. Regardless of where we are, and where we are really from.

And as Nelson Mandela said, “It always seems impossible, until it’s done”

Zrinka Bralo

Zrinka Bralo is CEO of Migrants Organise, an advice and campaigning organising platform for migrant justice. She is originally from Sarajevo, where she was a journalist and worked with international war correspondents during the 90s siege. She came to the UK in 1993 and, as a refugee, has been organising for migrants and refugee justice ever since.