Cover photo: An Iranian girl lets her hair blow in the wind as she shops in the Tajrish shopping area in Tehran, Iran, April 27, 2023. ©Maryam Rahmanian

The possible’s slow fuse is lit by the Imagination.

– Emily Dickinson

From the beginning of the Jina uprising in September 2022 in Iran, the Iranian women’s struggle made it to the front pages of journals and newspapers around the world. Images of women dancing around a fire and throwing their headscarves into it, travelled to many countries alongside the slogan “Women, Life, Freedom”, which was chanted in numerous languages. The collective joy lived by the protestors in Iran transcended borders. And the slogan itself was well suited for such circulation, having transnational roots in the Kurdish resistance.1 Indeed, what was witnessed in Iran was not a sudden incident out of nowhere; it echoed a historical precedent established over a century in the women’s movement. The flames blazed by women during the Jina uprising were the same as those lit by women at the beginning of the 20th century when the “Society of Patriotic Women” (Jam’iyat-e Nesvân-e Vatankhâh) gathered in Tehran’s Toupkhaneh square — a central public square popular for protests — and set copies of a book named Women’s Deception, on fire. Considering the repressive socio-religious context of the time, these women were arrested for protesting against widespread misogynistic ideologies and faced threats, insults and restrictions that might have slowed them down during their journey, but could never stop them.

The purpose of this article is to travel alongside the two historical fires over a century apart.

The flames blazed by women during the Jina uprising were the same as those lit by women at the beginning of the 20th century when the “Society of Patriotic Women” (Jam’iyat-e Nesvân-e Vatankhâh) gathered in Tehran’s Toupkhaneh square — a central public square popular for protests — and set copies of a book named Women’s Deception, on fire.

The objective is not to search for a history of beginnings and endings or to find the first and last groups’ achievements in each period. Notions such as achievement, change, and development will not be used, as I believe a large part of the women’s movement, and social movements in general, are invisible: they can’t be traced to incidents and events. In the article I explore the radical potentialities opened by the Iranian women’s imagination, which they articulated as part of their journey to discover alternative realities. Their questioning of what was once deemed sacred, coupled with the liberation of their imagination from the dominant society over time, has brought us to the current era, characterised by the slogan “Women, Life, Freedom.”

What follows serves as an episodic historical account encompassing three distinct periods: the constitutional era, the Pahlavi era, the aftermath of the 1979 revolution and finally the Jina revolt.

While it’s true that the word “feminism” entered the Iranian intellectual discourse during the 20th century and the formation of women’s groups, associations, newspapers, and journals can be traced back to this period, it is crucial to not overlook the movement’s roots in an even deeper historical context.2 It is also important to note that the women I focus on in this article are mainly those belonging to the upper-class in Tehran or metropolitan areas.3 Additionally, it is crucial to acknowledge that this article does not claim to provide a comprehensive overview and may not cover all aspects of the subject matter.

The Constitutional Revolution: Throwing Patriarchal Ideologies Into the Fire

Badrol Molouk Bamdad, a woman historian, described the women in the Constitutional Revolution era as follows: “Girls were trained to stay silent while sitting in a corner from an early age. They were trained not to ask questions and not to be curious. They lacked self-confidence and grew up pitiful, depressed, and inanimate. Even their little brothers, of the masculine sex, dominated them and ordered them around. A sense of inferiority, fear, and surrender was common among women.”4 This description reveals much about the socio-psychological state of women living in a historical context where women’s education was discouraged and even prohibited by religious and traditional authorities who deemed it both dangerous and sinful. Where the act of writing was viewed with suspicion; where it was asserted that women should only attain a level of literacy sufficient for the recitation of the Quran;5 where women were required to cover their bodies with a black Tchador and their faces with a white burqa and to appear in the public sphere as invisible and indistinguishable.

It was in this oppressive context that women began taking part in the political debates and mobilisations leading to the Constitutional Revolution that swept through the country at the beginning of the 20th century. As Iranians began to envision alternative systems of governance beyond the monarchy, women became active participants in the making of society in the prevailing socio-cultural landscape of the time. Public opinion was unfavourable on women’s rights issues, and the political activities of women had nationalistic roots and motivations. Regardless, the fact of their participation in the Constitutional Revolution was revolutionary in surpassing the traditional and theocratical walls that blocked any imagination of women taking part in the making of society.

Women began to initiate organised efforts to advocate for sanctions on imported (foreign-made) products and to promote the country’s economic independence: they campaigned for donations in order to establish the first National Bank of Iran, and they urged men to participate actively in making the constitutional revolution happen.6 However, as the revolution took place, women were set aside from the political sphere, expelled from the streets to their houses, and were listed among foreigners, children, non-Muslims, murderers, thieves, etc., who were not allowed to vote.7 Despite this turn, women gained a perspective on an alternative reality where they could participate in shaping societal discourse—such an unfolding of the imagination would lead to the emergence of women’s rights discussions.

Inspired by the political transformations occurring in the country and influenced by women’s movements elsewhere, Iranian women started establishing groups, associations, newspapers, medical centres, and schools. Their objectives included advocating for the right to education, urging reforms in family laws such as divorce regulations and polygamous marriages for men, and asserting their status as individuals with the ability to think, criticise, govern, and express themselves. The primary objective of women activists during this era was mainly to inform, particularly by educating and empowering women; enabling them to form opinions and play active roles in the public sphere. While these activists believed in the potential for equality between men and women, their efforts also acknowledged and accepted the prevailing societal perception of women’s inferiority; considering uneducated women untrustworthy and unprepared.

Pahlavi’s Coup D’Etat: The Dying Down of a Fire

Some may argue that when Reza Khan came to power, certain goals that women had long been fighting for were achieved. This might appear true in some respects when viewed through an achievement-oriented lens.8 It is undeniable that he put an end to debates about the Hijab through his infamous Hijab interdiction, known as the Kashf-e-Hijab. This decree prohibited women from going out onto the streets while wearing the Hijab. Gendarmes, previously tasked with ensuring that women were fully covered in black Tchadors and white burqas, now had the responsibility of forcibly removing the Hijab from women’s heads.

Historians have criticised such drastic actions and have analysed their consequences for women’s rights, the progress of movements and their capacities to gain public support. As my article focuses on a history of Iranian women’s social imagination, my analysis is narrowed to another critique: the privation of women’s agency, coupled with the hijacking of their efforts to attain equal rights, and the pretence that these rights are benevolently bestowed upon them by men in power. Each problem can be considered as a legacy of the Pahlavi dynasty that the Iranian women’s movement has been burdened by. As women came together, initiating activities with a strong belief in their rights and capacity to participate in the public sphere, the institutionalisation and centralisation of all women’s groups under a single governmental association hindered their ability to assert agency. Their efforts were overshadowed and co-opted under the auspices of Reza Khan Pahlavi.

Long before declaring the Hijab illegal, Reza Khan implemented regulations to prohibit the activities of communist parties and anti-monarchists. Journals and newspapers, many of which defended women’s rights, faced heavy censorship. Fifty newspapers were banned, leaving only governmental and official journals active. Women’s journals and newspapers were no exception, and over a period of three to four years, all women’s groups and associations were dismantled and integrated into a single association named the Women’s Club (Kanoun Banovan) which received orders from above, with Ashraf Pahlavi, Reza Khan’s daughter, as its head.9

On January 8, 1936, Reza Khan declared the day of Kashf-e Hijab in a speech, framing it as a moment when women could finally ‘enter the society.’ However, his narrative omitted the women who were already active members of society before his rise to power and disregarded those who had been fighting for education and participation. While proclaiming the day as an opportunity for women to take on new roles through jobs and contribute to the country’s economy, he overlooked the many women in rural areas who were already working and did not require his permission or help to ‘serve’ their country. There was little consideration for the idea that perhaps the best way to facilitate women’s participation in society would be to grant them the freedom of choice regarding their Hijab.10

Institutionalisation, centralisation, and control persisted during the second Pahlavi era. And despite certain accomplishments, the imagination of Iranian women and their belief in their agency were confined to the predetermined roles of motherhood and wifehood. While in the 1920s, women discussed gender equality in terms of physical strength, educated women of the 1950s acknowledged the stereotypes that regarded them as weak and inferior.11 The representative nature of all the legislation promoting women’s rights, together with the erasure of public debates led by independent women, deprived them of their agency and self-confidence. Consolidating diverse women’s ideas and groups into a single institution highlighted that the mere act of educating women does not automatically result in the reclaiming of their subjectivity and agency; especially if the education is focused on repressing their ability to question and brainwashing children to become obedient adults. Pahlavi’s changes were not only limited on an achievement-oriented representative level but also induced a long pause for the movement as such—at the very moment when it was gaining momentum.

The Islamic Republic: Tracing Back the Slow Fuse Leading to the Jina Uprising

While the Pahlavi era is recognised for instituting compulsory education—considered one of its achievements—it is crucial to acknowledge that by 1979, 60% of Iranians remained illiterate.12 Hence, it comes as no surprise that religious figures, including Ruhollah Khomeini, could easily gain women’s loyalty to religion. Similar to the Constitutional Revolution, many women participating in the protests followed their religious leaders, which meant their primary focus was not the pursuit of women’s rights.

On the other side, within leftist and liberal groups and parties as well, women’s rights were a marginalised issue. Although women actively took part in political parties and, in some of them, created women-specific branches, women’s rights issues were still mostly something to be discussed after the revolution and were not considered a key subject. In a sense, the history of women’s political engagement during this revolution repeated itself. Women actively took part in both the Constitutional and the 1979 protests, but they were pushed back to the domestic realm in the aftermath of both.

Yet, just as the Constitutional Revolution, women’s active engagement in the protests gave them the capacity to organise and imagine an alternative reality where freedom and equality would be foundational values. In contrast to the Constitutional Revolution, 1979 was a setback for the women’s movement: new obligations on the Hijab, heavy policing and monitoring of women’s bodies, lowering the age of marriage, prohibiting women from taking high-ranked jobs and firing them from their previous positions; imposing gender divisions in universities and schools that deprived women and men of the opportunity to educate and grow up beside each other, etc. Although confronted with these stifling policies, the revolutionary experiences lived by women in 1979 wouldn’t easily fade away. Women re-found themselves as political beings capable of imagining and bringing about change.

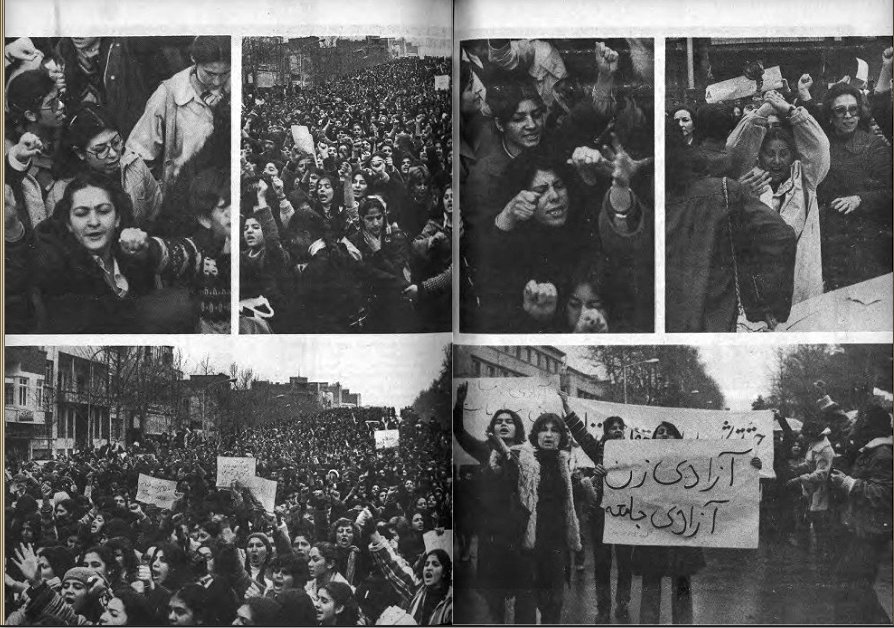

The organisation of large-scale protests against compulsory Hijab laws after the revolution on March 8, 1979, was one of the outcomes of heightened self-awareness and the experiences of women involved in political groups. Thousands of women gathered to stand against the remarks made by Ruhollah Khomeini on 6 March 1979, saying that although women’s roles in the workplace and presence in society are tolerated, these roles shouldn’t be against the laws of Sharia and the Hijab. The protests, like many other protests in the upcoming years, were repressed and didn’t bring about the change they were aiming for.

With the Iran hostage crisis in November 1979 and the Iran-Iraq war in September 1980, the momentum of the women’s movement, which had only been gaining strength, relented. Repressions instilled a sense of desolation and despair replaced motivations to organise. In such a landscape, a paediatrician, psychiatrist and political activist named Homa Darabi, burned herself to death to protest the obligatory hijab law in March 1994, chanting, “Down with dictatorship, long live freedom, long live Iran.”

In the repressive landscape created under the shadow of the war, mass executions of dissidents began in 1981. Thousands of leftist thinkers and activists were killed without any clearly organised objections.13 While the mass executions of 1988 were also carried out amidst a quiet public, families and especially mothers of the executed organised group and initiated gatherings, which can be regarded as the first steps towards the cultivation of a network that would take form as the Dad-Khahi (Justice-Seeking) Movement. Dad-Khahi has only expanded and multiplied over the years, responding to the repressions that resulted in the killing of protesters during demonstrations of 2009, 2010, 2017, 2019, and 2023. Over these years, the movement has intensified, shifting from reformist demands to radical imaginings of the regime’s overthrow. Women, mostly Dad-Khah mothers, initiated various groups and organised political activities beyond seeking justice and remembrance of their lost ones: they have advocated for other political prisoners at risk of execution, supported their families, and, in a more recent timeframe, demanded the abolition of capital punishment. A very bold and clear example of this is when Sherafat Zarini, a member of Mothers for Peace, set a hanging rope on fire in the backyard of her house, and ever since the execution of her son in 2018, she has supported protests and at-risk prisoners.

This example serves as an illustration of the political activism of Iranian women during the Islamic Republic’s reign. In comparison to the 1900s, political activism got out of the hands of metropolitan women of the upper class. Led by initiatives of women who were well-informed and well-educated, not because of their family backgrounds or encounters with Western women’s movements, but through their lived experiences—they required no superior institution to inform or educate them. This is also considered to be one of the unintended consequences of oppressive measures taken by the Islamic Republic to isolate women and control their presence in the public sphere. The Islamization of education has paradoxically resulted in women appearing in the public sphere more than before. Traditional families, now trusting the “safety” of educational establishments due to this process, permitted their daughters to attend school and even travel to other cities for universities. The compulsory hijab and gender divisions in universities reassured these families that their daughters’ newfound experience of independence would not conflict with their traditional beliefs.14 Yet, this independence has led to the critique of religious and traditional values, challenging the expectation for women to primarily see themselves as ‘mothers.’

A women’s rights demonstration took place in Tehran’s Haft Tir Square in June 2006, during which police beat and arbitrarily detained demonstrators. ©Arash Ashourinia

Returning to the notion that many social movements remain invisible, as mentioned in the beginning, the Iranian women’s movement persisted through forms of everyday resistance, notably disobedience against compulsory Hijab rules. Although the mass protests in March of 1979 were never replicated in terms of mass mobilisation and organisation, protests against the Hijab never truly ceased. Over the years, women have resisted the so-called moral police responsible for enforcing dress codes in the streets.

Women have also pushed against these standards in less visible manners by wearing colourful dresses and refusing to cover their hair fully. This day-to-day pushback culminated in a pivotal moment in 2017 when Vida Movahed, a young woman in Tehran, climbed onto an electrical box in Enghelab Street. There, she stood with her scarf as a flag instead of on her hair, and without saying a word, expressed the desire of women to be present in public without the fear of the police; dressing freely, ignoring religious and political controls.

And yet again, while the “Girls of Enghelab Street” movement ceased after a few months of these individual yet collective protests from different cities around the country, the imagination of women as capable of standing before the police and not wearing the Hijab stayed alive: women continued not following the laws of Hijab during their day-to-day life. They did this by reclaiming the social imagination of the public sphere, changing the meaning of urban objects, such as electric boxes, making public space something that belonged to them.15

The disappointment felt by women at the lack of visible change in the constitution during the first two decades of the Islamic Republic’s rule, combined with their daily experiences of confronting oppressive laws and regulations, as well as their awareness of historical movements in Iran and beyond, motivated them to go beyond mere bureaucratic reforms and demand more radical changes. The system’s resistance to even the slightest reform or change compelled women to seek support beyond governments and institutions. While the aim of this article is not to generalise and overlook the variety of feminist movements in Iran, it is true that the distinctions between the women standing around a fire burning their scarves and the women who gathered around a fire burning hostile books targeting women, can primarily be found in their approach to change and their refusal to rely on institutions and superior forces for their rescue.

Dancing Around a Fire

When Jina (Masha) Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, was stopped by the so-called morality police in Tehran on 13 September 2022 for not following the Islamic Republic’s mandatory headscarf guidelines, she was faced with violence after resisting detainment in the police van. She fell into a coma during the arrest and was taken to the hospital. Three days later, on 16 September 2022, Jina passed away in Kasra Hospital of Tehran, and the fire of her resistance spread.

Protests already began while Jina was in the hospital, but intensified after she passed away. At her funeral in Aichi cemetery in Saqqez, a small village in Kurdistan, Iran, more than 10,000 people gathered. During the burial, the women took their headscarves off and began waving them while chanting “Jin, Jian, Azadi”, which has since become the main slogan of the current movement, and which comes from a history of Kurdish resistance.16 On that day, Jina’s family wrote on her temporary tombstone: “Dear Jina, you won’t die, your name will become a symbol.” And it did become one: A vast revolt began, and many Iranians and even non-Iranians from different regions and countries joined the movement. Anonymous groups of women began organising and publishing reports and critiques, primarily on social media, breaking through the centralisation of knowledge and its domination by women living in big cities. An unprecedented circulation of knowledge and experiences has been initiated. While there is still a considerable journey ahead for its development and nurturing, the mere inception of this invaluable dialogue distinguishes the Jina uprising as a force pushing beyond predefined boundaries and frameworks. Women are actively assembling to cultivate their unique body of knowledge, shattering the ingrained perspective of perceiving them solely as consumers of others’ imagination. This transformative movement acknowledges women not merely as recipients but as inquisitive minds and creators of meaning, marking a pivotal shift towards a more inclusive and empowering narrative. The mere establishment and commencement of such a precious dialogue is what highlights Jina uprising as a prompt to imagine and go beyond predefined walls and frameworks.

Footnotes

- In Kurdish, the slogan “Jin, Jian, Azadi” can be traced back to a 40-year-old fight and resistance led by Kurdish women against various forms of political Islamism, extremism, political and gender violence, colonialism, nationalism, capitalism, and totalitarianism. Upholding its core principles, this slogan transcended local borders and reached various movements. (Rostampour, 2022) ↩︎

- It seems that the word feminism was first introduced to Iranians in “Tajadod” newspaper by Rafi Khan Amin and Taghi Raf’at. (KhosroPanah, 2002) ↩︎

- The notion of class should be approached with caution, considering Christine Delphy’s critique of generalising the understanding of ‘class’ to women. Many women, regardless of their social class, experienced oppression. They were married at early ages, faced familial oppressions, and dealt with restrictive divorce laws and regulations. Consequently, they developed a profound understanding of women’s oppression that transcended their class origins. ↩︎

- (Bamdad, 1969, p. 57) ↩︎

- (Sanasarian, 1982) ↩︎

- (KhosroPanah, 2002) ↩︎

- (KhosroPanah, 2002) ↩︎

- It should be noted that the rules and regulations pertaining to women’s rights did not aim for women’s and men’s equality. They were primarily focused on the Hijab and education, undertaken to keep pace with the modernisation efforts and outward appearance in front of Western European countries and neighbouring nations, such as Turkey. As for laws such as divorce or polygamous marriage for women, changes were non-functional as the King himself had three wives and firmly believed in the role of women to be mothers and housewives. ↩︎

- (Sanasarian, 1982) ↩︎

- (Chehabi, 1993) ↩︎

- (Sanasarian, 1982) ↩︎

- (Sanasarian, 1982) ↩︎

- A lack of scholarly support about the massacres of 1981 leads to uncertainties regarding empirical data, but some findings report the killing of between 5000 to 10000 dissidents during a period of three years. (Mohajer, 2020) ↩︎

- (Tohidi, 2010) ↩︎

- (Ooryad, 2020) ↩︎

- (Rostampour, 2022) ↩︎

Sources & Further Reading

- Chehabi, H. E. (1993). Staging the Emperor’s New Clothes: Dress Codes and Nation-Building under Reza Shah. Iranian Studies.

- Daneshgar, A. (2022, 09 15). radiozamaneh. Retrieved from radiozamaneh: https://www.radiozamaneh.com/730738/

- Fallaci, O. (1976). Interview with History.

- KhosroPanah, M. (2002). The Goals and Combat of Iranian Women From the Constituional Revolution to Pahlavi . Payam Emrouz.

- Nahid, A. H. (1981). Iranian women in the Constitutional Revolution.

- Ooryad, S. K. (2020). Conquering, Chanting, and Protesting: Tools of Kinship in the Girls of Enghelab. Dans A. H.-v. Gero Bauer, Kinship and Collective Action: in Literature and Culture.

- Rostampour, S. (2022, October 27). Jen, Jian, Azadi means “it’s time”. Retrieved from Radio Zamaneh website.

- Sanasarian, E. (1982). Women’s rights movement in Iran: mutiny, appeasement, and repression from 1900 to Khomeini. University of Michigan.Tohidi, N. (2010). The Women’s Movement and Feminism in Iran: A Glocal Perspective. Dans A. Basu, Women’s Movements in the Global Era (pp. 375-414). Routledge.

Saba Memar

Saba Memar, born in 1991, is a feminist researcher and journalist from Iran. She studies political science at Paris 8 university and has contributed to several independent Iranian media outlets. Her research interests include social imagination, improvisation, and the interrelation of art and politics in social movements.