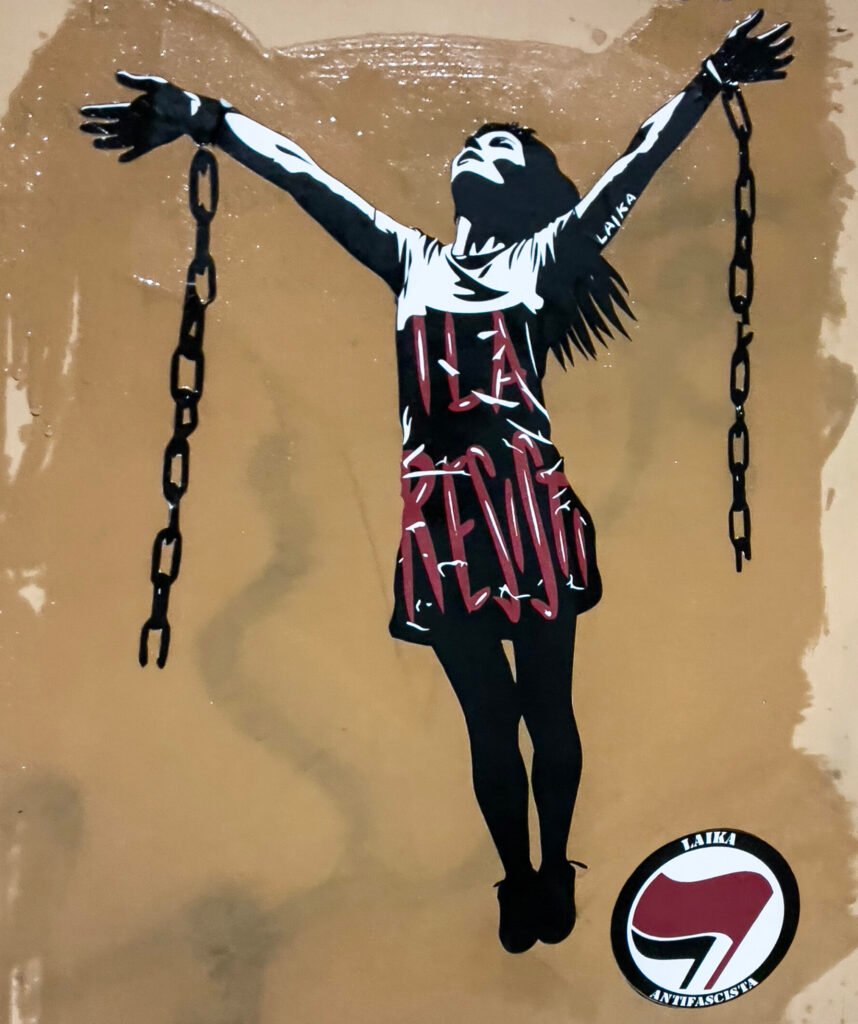

Cover photo: Solidarity poster for Budapest trial defendant Ilaria Salis by Amar3 in Rome, on April 25, 2024. © Ludovica Anzaldi

On March 28, 2024, the streets surrounding Milan’s main courthouse, the Palace of Justice, are swarmed with different branches of Italian law enforcement. The municipal police have brought one patrol car, casually parked next to a newspaper kiosk. State police and military police (the Carabinieri) can be seen on the side streets, sporting riot gear in their trademark armored vans, light and dark blue respectively. The scenery does not yet make a strikingly unusual sight in the city’s increasingly policed streets.

However, the plain clothes agents of the General Investigations and Special Operations Division—a domestic intelligence department commonly known as “digos” by its Italian acronym—filming everyone and everything imply there is something more than ordinary going on during the otherwise silent siesta hours.

A few dozen people begin to form a picket in front of the court. Growing towards 60 people, the crowd is waiting for news about Gabriele Marchesi’s trial: “Neither prison nor extradition—Free all Antifas—From Milan to Budapest” reads the banner that two people are fixing between street light poles. The 23-year-old Marchesi stands accused of assaulting two neo-Nazis in Budapest, Hungary, in February 2023, allegedly on the orders of an international “criminal left-wing extremist organization.”

Marchesi has been under pretrial house arrest and a strict communications ban since November 2023, after being arrested by Italian authorities on a European Arrest Warrant (EAW). Milan’s Court of Appeal is deciding upon his extradition to Hungary where he would face charges in a judicial system that has deteriorated under successive far-right governments. All led by the country’s authoritarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party since 2010. In Hungary, he faces up to 16 years in prison.

The Milanese court has postponed its extradition decision five times, waiting for Hungary to clarify several questions regarding the state of prison conditions, the rule of law, and the independence of the judiciary in the country.

This sight in front of Milan’s Palace of Justice is one of the symbolic scenes in the biggest anti-fascist trial of our generation. Almost 10 times larger than the Colosseum, the 30,000-square-meter courthouse is perhaps the most significant, grotesque, and intimidating architectural legacy of Benito Mussolini’s reign in the city. Designed in 1930 by Marcello Piacentini, “the most powerful of Fascist architects,” the courthouse’s exterior combines plain modernism with pompous Roman iconography and Latin phrases about ivstitia. Looking at this colossal, menacing monument of Fascist rule and its Kafkaesque slogans about justice, one is inclined to think no good news has ever come out of its doors. Marchesi’s supporters’ appeals bounce off its 60-meter-tall walls of unwavering, white Vallestrona marble.

As the day turns towards late afternoon, the news finally breaks out: “Gabri is free!” The judge rules in Marchesi’s favor and forbids his extradition, citing the “real risk of inhuman and degrading treatment” in Hungary, the “real risk of violating fundamental rights” and a “failure to respect the principle of proportionality.” The house arrest and communication ban are lifted with the same ruling.

While the news ignites Gabriele’s friends and supporters in triumphant jubilation, the decision concludes just one act in the international judicial drama, whose epicenter lies almost a thousand kilometers away and which is far from concluded.

A Continental Hunt

Gabriele Marchesi is but one of 17 people pursued by Hungarian authorities in relation to anti-fascist activities in the country’s capital on February 11, 2023. Ilaria Salis, an Italian woman from Milan’s neighboring town Monza, has been incarcerated in Budapest since then. Two other people, both German citizens, were arrested by Hungarian police and incarcerated likewise. On December 11, 2023, a German anti-fascist was arrested in Berlin, and on May 5, 2024, a second one in Nuremberg. With an EU mechanism called European Arrest Warrant, the Hungarian authorities have pursued yet another 11 suspects throughout the Union.

The continental reach of the Hungarian arm of law casts a long shadow over the defendants’ future. Ilaria Salis has documented her prison conditions in detail: untranslated court documents; interrogations without a defense lawyer; overcrowded prison wards infested with cockroaches, mice, and bedbugs; malnutrition; and the list continues for 18 pages. These accounts, sent as a letter to the Italian consulate in Budapest, were later published via her lawyers.

In February 2024, Salis’s case took an international spin when images of her being dragged on a leash to the Budapest court spread around Europe. She rapidly became a symbol for what critics, such as the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, have called the “cruel, inhuman, and degrading” nature of Hungary’s penal system.

“European Arrest Warrants become a very problematic tool when abused by countries where prison conditions are awful and there is a risk that a person doesn’t have the right to a fair trial,” says one of the defendants, Rexhino A., who has battled extradition to Hungary in Finland. At the time of the interview, he is waiting for Finland’s Supreme Court to give its ruling on the extradition that he perceives as politicized persecution.

“In Hungarian television, they frequently talk about the so-called ‘Antifa terrorists’ to reinforce certain narratives and shift the public opinion,” says Rexhino. Also the defense documents submitted to his extradition trial argue that the case is politicized, referring to Hungarian government officials’ comments in national media and on the social media platform X.

Typical to EAW cases, Rexhino is detained in GPS-monitored house arrest until he receives the Supreme Court ruling. Regardless of the outcome, the case may already inflict long-lasting consequences on him.

“Due to this measure of limited freedom, I potentially cannot get certain jobs that require police or security police approval,” says Rexhino about the impact of the EAW and the underlying charges. He lists the IT sector, parts of public administration, the private security sector, and works at companies that handle sensitive information, as examples of professions where a charge of criminal association can prevent employment. In Finland, the security police can also evaluate unresolved criminal cases in its security clearance vetting decisions.

In the charges and the subsequent EAWs, it is not immediately clear what precisely is the criminal association that allegedly unites the 17 defendants across Europe. The Hungarian criminal law (article 459) defines criminal association ambiguously as “a group that consists of at least three persons, is established for a longer period of time, is organized hierarchically and operates in a conspiratorial manner to commit intentional criminal offenses punishable by at least five years of imprisonment.”

The Hungarian authorities have provided CCTV footage, construction tools, and other material evidence, as well as fragmentarily documented narration of events in Budapest around February 11, 2023, to describe the association. All other issues aside, the evidence undeniably falls short of establishing the “for a longer period of time” criteria as required by article 459.

At this point, the Hungarian authorities’ argumentation turns circumstantial and more difficult to follow.

The prosecution implies (with no clear evidence) that the defendants from different European countries are all part of a regional, East German, phenomenon that the German press has named “Hammerbande.” Meaning Hammer Gang, the name was assigned to a group of people prosecuted for assaults against neo-Nazis in the eastern German states of Thuringia and Saxony between 2018 and 2020. On May 31, 2023, four German anti-fascists were sentenced to prison for forming a criminal association to carry out these attacks.

In the Hungarian prosecution, with a striking absence of evidence, the Hammerbande connection spins the narrative from the streets of Budapest to a significantly longer period of time, ticking the last criminal association criteria required by the Hungarian penal code.

“That is the strategy of both the Hungarian and the German police. This is the framework in which they want to work,” says Rexhino promptly. “To justify this big operation around Europe, they have this narrative of ‘huge criminal association’ in Europe that is organized for the purpose of beating up people.”

The somewhat peculiar notion of a pan-European association organized for the purpose of beating people up is to be viewed in the light of the events in Budapest around February 11, 2023.

A Day of Nazi Revanchism

February 11 is the occasion of Hungary’s biggest annual neo-Nazi mobilization, the so-called Day of Honor. It is a day of Third Reich nostalgia and revanchism in commemoration of Budapest’s Waffen SS-Wehrmacht garrison and its Hungarian allies who were left to hold the city against Soviet Union forces. February 11, 1945, marked the Nazi garrison’s escape attempt to break through the Red Army siege at the end of World War II.

The event was practically forgotten during Soviet rule, only reanimated after Hungary’s independence and the arrival of a burgeoning neo-Nazi skinhead subculture in the 1990s. The neo-Nazis rebranded the fight for Hitler’s rule in Hungary as a heroic epic: the defense of Western Europe against communism.

“This message completely fails to recognize that the German and Hungarian troops were actually defending Hitler’s Third Reich and with it Nazism and the Nazi ideology,” says Hunyadi Bulcsú, an expert on far-right politics at the Hungarian think-tank Political Capital Institute. “The gathering is organized and attended by hard-core right-wing extremists and neo-Nazis from Hungary and other countries, especially Germany, but often from Serbia, France, Bulgaria, Italy, and Poland.”

Over the years, the Day of Honor has grown to become one of the biggest neo-Nazi mobilizations in Eastern Europe, attracting hundreds, some years thousands of participants from across the continent. According to Bulcsú, one of its main organizers, Legio Hungaria, has established “close cooperation with fellow neo-Nazi and extreme right organizations” in many European countries.

The event has reportedly been frequented by organizations such as Blood and Honor, Combat 18, Nordic Resistance Movement, as well as German Die Dritte Weg and Die Rechte. Blood and Honor is banned in several countries due to a terrorism threat while Nordic Resistance Movement was implicated in a series of bombings in Sweden, and banned in Finland following its militant killing a passer-by during a street event in the center of Helsinki in 2016.

The Day of Honor commemoration has been banned by the Budapest police for several years, although the ban has not been enforced consistently. The event has been organized every year one way or another, most recently in 2024 at an undisclosed private venue. The second major event organized to mark the occasion, the Outbreak Tour, in fact continues to receive state sponsorship in the form of weapons, uniforms, and Nazi memorabilia from Hungary’s Military History Museum, as well as directly in cash, according to two recent inquiries in the European Parliament.

“While the two events are different, and so are the attendees, the main message of both events is the same and completely false, celebrating Nazi ideology,” says Bulcsù while confirming Outbreak Tour’s continued state support. In 2023, the two founders of the organization behind the Outbreak Tour, Zoltán Moys and Oszkár Kenyeres, were decorated with Knight’s Crosses of the Hungarian Order of Merit.

Hungary’s prime minister Orbán is known to cultivate ties with far-right movements both in Hungary and abroad. Orbán has embraced the “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory and molded it into a state ideology. According to Bulcsù, Orbán’s Fidesz party is sensitive to far-right themes and how they resonate with society, as the party pursues “total control of the right.”

“Fidesz does not openly confront extremist organizations and their activities politically and publicly, but rather tries to ‘outsource’ the problem to authorities such as the police and the courts,” he says. “Publicly, they take over the issues. For example, a few years ago, the media organized by Fidesz gave positive coverage to the Outbreak Tour and the idea behind the Day of Honor.”

The Hungarian government’s collusion with far-right movements has not only created a breeding ground for local fascist movements, but also offers a safe haven for a variety of internationally oriented initiatives ranging from boxing tournaments and white power concerts to the multilingual neo-fascist publishing house Arktos. Among these initiatives is, naturally, the Day of Honor.

Over the years, the Day of Honor has seen the growth of an anti-fascist opposition and counter-protests. It has not been untypical also for anti-fascists from other Hungarian cities, and even from abroad, to coalesce in the city around the date. In 2023, as usual, hundreds of Nazies gathered at Buda Castle defying the ban. At the same venue, some 200-250 anti-fascists held a counter-demonstration. While the official events went on without major tensions, their sidelines were marked with unprecedented violence: besides several incidents of neo-Nazi violence, local media broke the news of what looks like hit-and-run attacks against the Nazis by masked people.

All 17 people that the Hungarian authorities pursue are from the anti-fascist side. They are charged for the mentioned hit-and-run attacks, some of which are documented in CCTV footage, as well as for forming a criminal association. The criminal association, in turn, is some kind of international extension of the eastern German group.

The EAWs: a Legal Quagmire

Already before properly starting, the Budapest trial has become a focal point of Europe’s clashing political realities, growing authoritarianism, and deteriorating rule of law. The international legal quagmire surrounding the alleged international criminal association has turned into a series of human rights trials in which Hungary’s conformity with EU norms has been questioned.

One instance, widely denounced by human rights platforms, has been the Orbán government’s reforms that politicized the country’s judicial system. In July 2023, Hungary faced disciplinary punishments following an awkward press conference where European Commissioners reportedly took pains not to mention Poland and Hungary too often by name when presenting their annual rule of law reports. The country has been condemned by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) for failing to prosecute and curtail fascist violence and fulfill its international obligations to protect ethnic minorities, particularly Roma people and Jews.

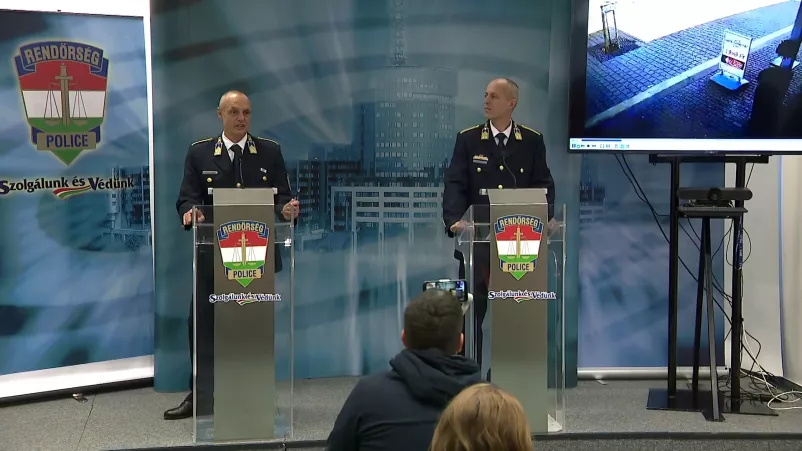

During the 2023 Day of Honor, the Hungarian police investigated neo-Nazi violence as relatively modest offenses, namely disorderly conduct and bodily harm. According to the info brochure of Ilaria Salis’s support campaign, in the vast majority of reported cases, the perpetrators were immediately released by the police. In the Day of Honor’s immediate aftermath, the Budapest police headquarters held a widely broadcast press conference where nothing was disclosed about these proceedings.

The press conference was all about the 24-officer strong task force that the Budapest police had rushed to set up to pursue anti-fascists. The task force was also supported by domestic and foreign secret services. Charged as a criminal association—which significantly aggravates the underlying bodily harm charges—Salis, Marchesi, and others face up to 16 years of prison.

“The concerning issue in this proceeding is the leap in the level [of repression], the use of criminal association charges against a political group and people who carry out political activities,” says Eugenio Losco, Salis and Marchesi’s Italian defense lawyer.

The ambiguous definitions of criminal or terrorist associations are known to provide a legal gray area for authoritarian countries like Turkey to imprison opposition figures, journalists, dissidents, and organizers without a clear personal offense. The related charges, such as membership in a criminal association or spreading terrorist propaganda do not tie criminal offenses to clearly defined and proscribed individual acts. Membership, for example, does not follow its standard meaning (being a member) but may also include any sort of remote or informal association, such as telephone contact or physical encounter at a suspicious time.

“So all the people who found themselves together with a group of anti-fascists that participated in the counter demonstration are contested, and those who were identified are obviously contested for membership in a criminal association,” continues Losco. The experienced defense lawyer is seemingly appalled by the prosecution. He calls the criminal association proceedings ridiculous.

The Hungarian investigators have not established any evidence about the creation of the association, its hierarchical structure (as required by article 459), its membership register, or the accused members’ roles inside the organization. In fact, evidence is lacking for any long-term contact or connection between the accused members and for even generic description of the organization’s scope, structure and functioning.

“All such investigative activity is absolutely absent in the trial file […] So there is an association because in Germany there were some similar events, and in Hungary there were some Germans. There is not much more,” summarizes Losco, adding that some of the German anti-fascists were implicated in the earlier German proceedings.

While the Hungarian authorities have struggled to establish an identifiable connection between the prosecuted individuals and the recorded acts of violence by masked assailants, the evidently post factum construction of the alleged criminal association has allowed them to expand their prosecution from the alleged perpetrators to their associates, and potentially associates’ associates. In total, 17 people are pursued for belonging to the criminal association, some of them already incarcerated for more than a year and others living as fugitives or in extradition limbo, while it is not shown that any association exists in the first place.

The ambiguous use of criminal, extremist or terrorist association charges are not just a peculiarity of the Turkish or Hungarian system, but an ever-deepening reality across Europe.

The direction of the Hungarian prosecution runs opposite to the freedom of association warnings which stress that an individual’s membership should not be penalized for any kind of association—even indisputably existing and clearly documented association—unless the association itself has been proscribed already earlier by an independent judicial body. However, the ambiguous use of criminal, extremist or terrorist association charges are not just a peculiarity of the Turkish or Hungarian system, but an ever-deepening reality across Europe as witnessed in the earlier anti-fascist trials in Germany.

“This [criminal association dispute] was probably born also from the input of the German governmental and judicial authorities who actively collaborated in the Hungarian proceedings,” says Losco.

In Germany, it is not uncommon, for example, to prove membership in a terrorist organization by combining purely circumstantial evidence, such as phone call logs, to constitutional political activities, such as organizing demonstrations, cultural events, or protests. Recently, Germany’s practices provoked the UN to call for protection for environmentalist protesters after they were persecuted as a criminal organization.

Some Nordic countries have also moved towards this direction; Sweden has openly done so to appease Recep Tayyip Erdogan in exchange for the country’s NATO membership—Finland already doing so earlier. However, Losco sees his home country as “the world champion” in charging criminal associations.

Due to its long history with organized crime, Italy boasts the most extravagant toolbox in Europe to suppress criminal associations. Losco recollects two examples of criminal association charges being used to penalize political activity: a Milanese housing association which opposed evictions and a Calabrian mayor who welcomed refugees to his municipality. According to him, prosecutors also pull terrorist association charges especially against the country’s anarchist movement, although nowadays the courts tend to reject these charges.

The truly continental problem arises from the fact that all EU member states are bound together by the European Arrest Warrant mechanism. Similar instruments, like Europol and Interpol Red Lists, have been repeatedly criticized to be vulnerable for abuse by authoritarian regimes. Turkey, for one, has even exploited Interpol’s Stolen and Lost Travel Document system to chase down the opponents of Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s reign.

The EAW, however, differs from other similar mechanisms because it is built on an assumption of common rule of law and fundamental rights standards within the EU. The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights summarizes the EAWs functioning in its recent report: “[The warrant] must be swiftly executed by the executing Member State, without examining the substance of the warrant, in the spirit of mutual trust and mutual recognition.”

“There is very little defensive space for a person who is pursued with an EAW because there is no possibility of defending oneself based on the merits of the accusation,” says Losco, referring to the fact that the EAW mechanism forbids extradition courts to examine the actual substance of the warrant. According to him, up to 90% of EAW cases result in extradition.

For defense, the EAW allows only what Losco calls a “very generic assessment” if fundamental rights are respected in the issuing country. While Marchesi’s extradition was stopped by the Milanese court on human rights grounds, securing fundamental rights is not regulated in the EAW mechanism itself.

Contrary to Marchesi’s outcome, in Rexhino’s case the Helsinki district court showed a different understanding. The court acknowledged systemic deficiencies in the Hungarian penal system. The judge’s somewhat counter-intuitive interpretation was that Hungary’s human rights violations are “only systemic” but not proven to apply to Rexhino personally, and thus there is no foreseeable risk that he would be subjected to them. After Finland’s Supreme Court refused proper re-evaluation of the verdict, Rexhino has requested an immediate ECHR intervention. The ECHR denied immediate “interim measures” against the state of Finland, but is currently processing his case.

The defendants’ situation is further complicated by the fact that an extradition refusal in one country does not constitute a precedent for other EU countries to follow. Even if Marchesi’s extradition was stopped in Italy, the Hungarian arrest warrant remains intact. Consequently, also Marchesi risks facing a renewed EAW and deportation trial in all other European countries, should he want to travel within the EU.

The risk was recently witnessed in Carles Puidgemont’s case when Spain pursued the Catalan independence leader with tactical issuances and withdrawals of EAWs in Belgium, Finland, and Germany in an attempt to find the weakest link to capture and punish him.

“The risk is there, and Gabriele is in a bit of a limbo at the moment,” confirms Losco, adding that he expects Hungary to also use global mechanisms, so-called “red alerts,” to pursue his client. While happy for the Milanese court ruling, he says that they still have to try to address the situation more completely at a later moment.

In the light of the EAWs legal architecture, the limbo is likely to continue until the charges expire, Hungary backs off from its international venture, or the EU reforms the EAW mechanism. In any case, it may take several years.

So far, Hungary has shown no signs of giving up. The EUs course does not seem any better. In July this year, The Council of The European Union, whose main role is to “define the EU political direction and priorities,” will rotate its presidency. The next president country will be a state with more than €20 billion EU funds frozen due its rule of law violations, a state ideologically closer to Moscow than to Brussels: Viktor Orbán’s Hungary.

History Will Judge

While the defendants’ future remains uncertain, the sporadic but controversial flow of news from Hungary has brought the country’s domestic circumstances to renewed international attention. People across the continent have awakened to a reality that somewhat faded from the news cycle after the formative years of Orbán’s power consolidation and the repetitive Jobbik scandals.

Ilaria Salis is expected to have her next court hearing on May 25. Her appeals to transfer to house arrest appear to be finally granted. For a bail of 40,000 euros, Salis is expected to move to a house arrest in Budapest, enforced with a GPS-monitoring bracelet.

“We are very satisfied,” commented her Italian lawyers to Italian newspapers. “Finally this nightmare for Ilaria ends, but the battle continues.”

In April 2024, Salis’s solidarity campaigns took a new turn that surely continues to keep the Budapest trial and her battle on the Italian and European agenda. After weeks of rumors and speculation, the Italian Green and Left Alliance nominated Ilaria Salis as its candidate for the European Parliament elections in June. The impact of her potential MEP status on her current incarceration remains unclear at the time of writing. If Salis is elected, Hungary should release her from prison and request the European Parliament to waive her parliamentary immunity before proceeding with criminal charges.

While Salis’s candidacy appears a surprising and irregular turn of events, it is not without historical precedents. In Italian political history, at least two examples stand out that resonate with Salis’s current situation.

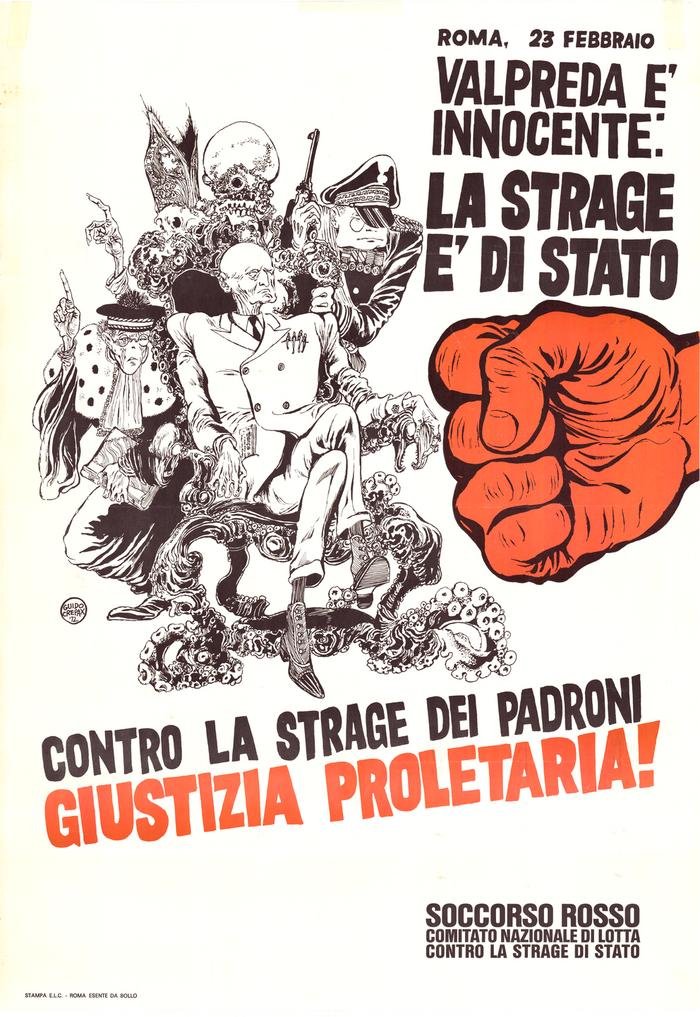

Pietro Valpreda (1932-2002) was a dancer by profession and an anarchist by conviction. In December 1969, Valpreda was arrested among the main suspects for the Piazza Fontana bombing in Milan. He was lynched in the media and sentenced to prison—still fortunate to avoid the fate of the second anarchist suspect, Giuseppe Pinelli, who died “accidentally” dropping out of the police headquarters window.

Despite the media lynching campaign, both Pinelli and Valpreda were empathized with and considered victims of what was later named a “strategy of tension”: Italian fascists, in collusion with secret services, conducting terrorist attacks and framing them on communists and anarchists to prepare ground for a military coup—should the Communist Party take over the Italian government democratically.

In this highly politicized atmosphere, the imprisoned Valpreda ran in the 1972 general elections. His candidacy was articulated as a move to protect a man whom his supporters believed to be an absolutely innocent victim of secret police machinations. Valpreda was not elected, but five years later he was released from prison and acquitted of all charges.

In 2004, more than three decades after the massacre, the Milanese court pinned the Piazza Fontana bombing on two members of Ordine Nuovo, a fascist paramilitary organization.

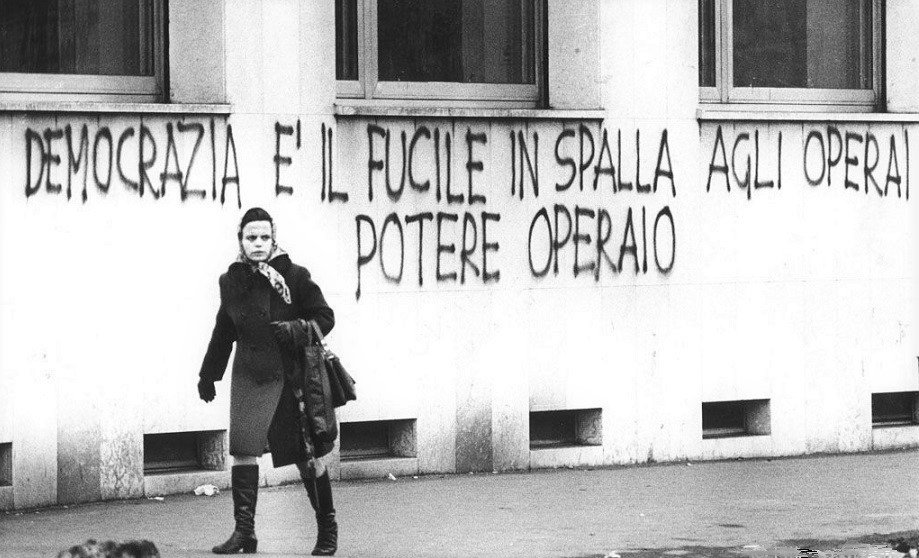

Antonio “Toni” Negri (1933–2023) was a controversial professor of political philosophy at the University of Padua. Besides his academic merits, Negri was known as a passionate leader of the Potere Operaio movement and one of the most prominent theorists of the Italian Autonomia, a radical reassessment of Marxist theory and praxis that consolidated into a combative social movement, strong enough to threaten the Christian Democrats and the Communist Party alike.

During the 1970s, Negri was accused of many things. Most importantly for the course of his life, he was accused of being an anonymous mastermind behind the Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse, BR), an urban guerrilla organization gearing up its attacks against the Italian establishment and fascist organizations. Negri was arrested in 1979, with the charge of being the secret BR leader as well as a participant in Prime Minister Aldo Moro’s kidnapping and execution. While his role as a revolutionary leader figure was never disputed, the charges were received as a ridiculous, false, and unjust crackdown on his completely unrelated activities with the Potere Operaio.

Four years after his arrest, the imprisoned Negri ran in the 1983 general elections. The rebel professor was successfully elected to the Italian legislature and subsequently released from prison. Before the Italian Senate voted to lift his parliamentary immunity, Negri had already fled to France where he lived for 14 years protected by the “Mitterrand doctrine.”

The three distinct cases of Valpreda, Negri, and Salis tie together half a century of political history and injustice in Italy, while similar cases in other countries come to evidence a global legal order. Decades come and go but the frenzied hunt of criminal conspiracies, extremist associations, and terrorist organizations—real or perceived—continue to uphold a cunning, unjust, rule of law.

Valpreda and Negri became the public face for the victims of the anti-communist hysteria that ran amok in the 1970s. Their trials became symbolic examples of the rampant secret service machinations that enforced a crack down on social movements. They are testaments to the unaccountability of governing institutions to society, crystallizing an unbearable gap between justice and law enforcement.

The Budapest trial is already becoming a symbol of the further deterioration of civil rights, frantic anti-extremism, and growing authoritarianism across Europe. It exemplifies alarming tendencies within the European Union where fascism is on rise and lurking in the liberal mechanisms of “mutual trust and recognition.” While people may have different opinions about the offenses in Budapest or speculations about the defendants’ role in them, one feeling increasingly stands above them all: Hungary is orchestrating an injustice of continental dimensions.

Henri Sulku

Henri Sulku is an editor of Turning Point with focus on political economy, people’s history, and resistance movements.

Edited: 23.5. cover photo changed.