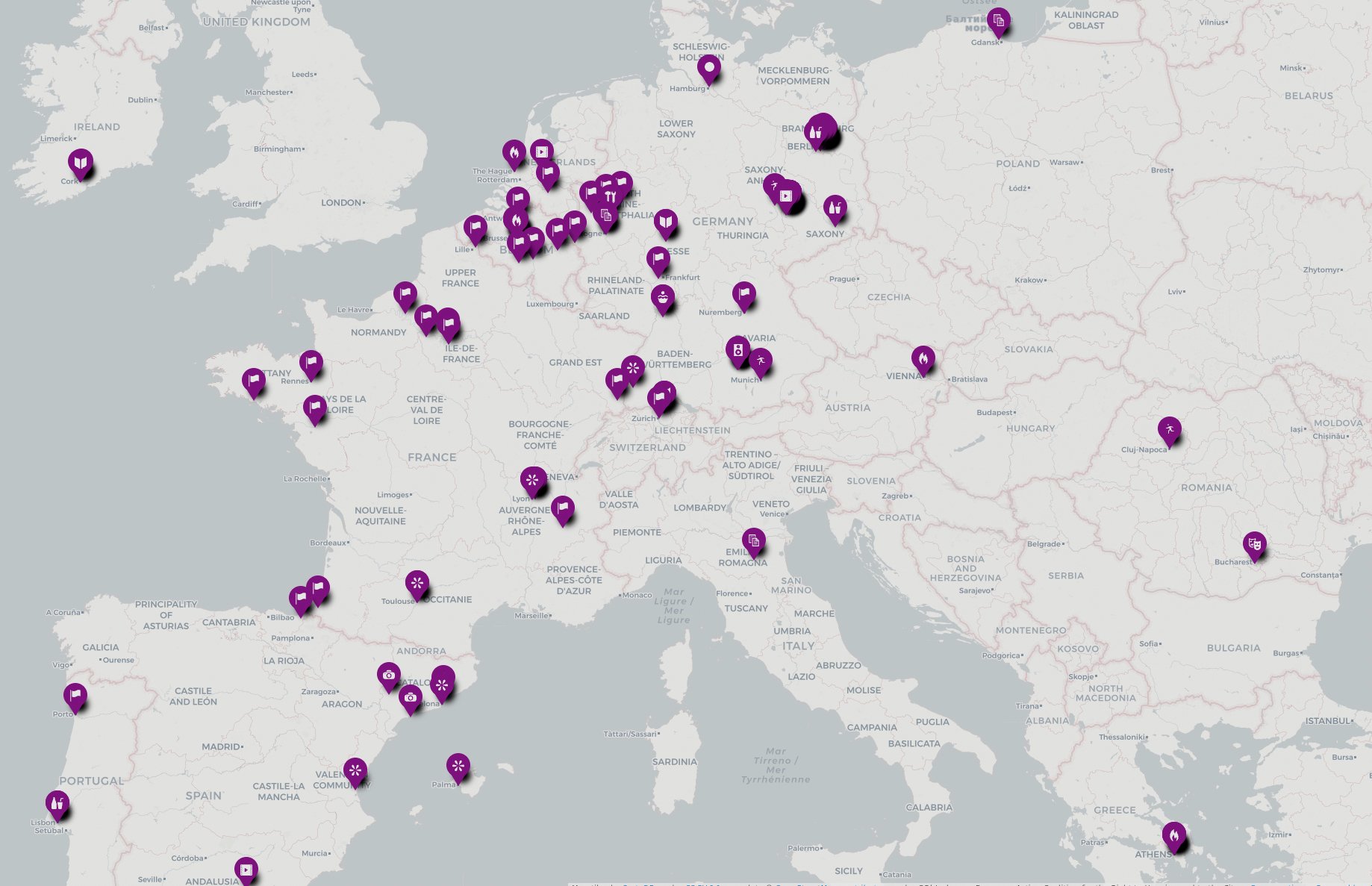

Cover photo: An interactive map showing Housing Action Days 2024 activities across Europe, created by the European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and to the City. Map tiles CC BY 3.0 CartoDB; map data © OpenStreetMap contributors under ODbL.

Every year, the Untold Festival takes place during the first days of August. In 2023, more than 400,000 people attended its 9th edition. To facilitate the short but massive influx of tourists, the Romanian city of Cluj-Napoca, with its population just around 300,000, is turned upside down for more than a month. During that time, access to the main public park and its surroundings is heavily restricted or forbidden. For four days, the city center witnesses a sonic war—besides residents, the surrounding hospitals are deeply affected by the nonstop sonic aggression.

For others, it is totally worth it. The local hospitality industry benefits directly and heavily from the one of numerous international festivals to be hosted in the city. Meanwhile, an average-sized apartment (60m2) is now let for 600 euro, up from around 300 euro in 2014. Foremost known as a university city, Cluj has become inaccessible to students.

Savvy investors have also taken notice: at the end of 2023, there were more than 17,000 landlords who owned between 3 and 10 housing units in the city, according to Cluj-Napoca Taxes Office. The number grew from around 13,000 in early 2020, indicating that a new social strata is taking shape. For the Romanian housing model, it is a novelty. Long hailed as a “super homeownership society,” this post-socialist country posed itself as a leader in private property led housing equality—no longer an accurate description of Romania (if it ever was one). And it is not the only case in Europe.

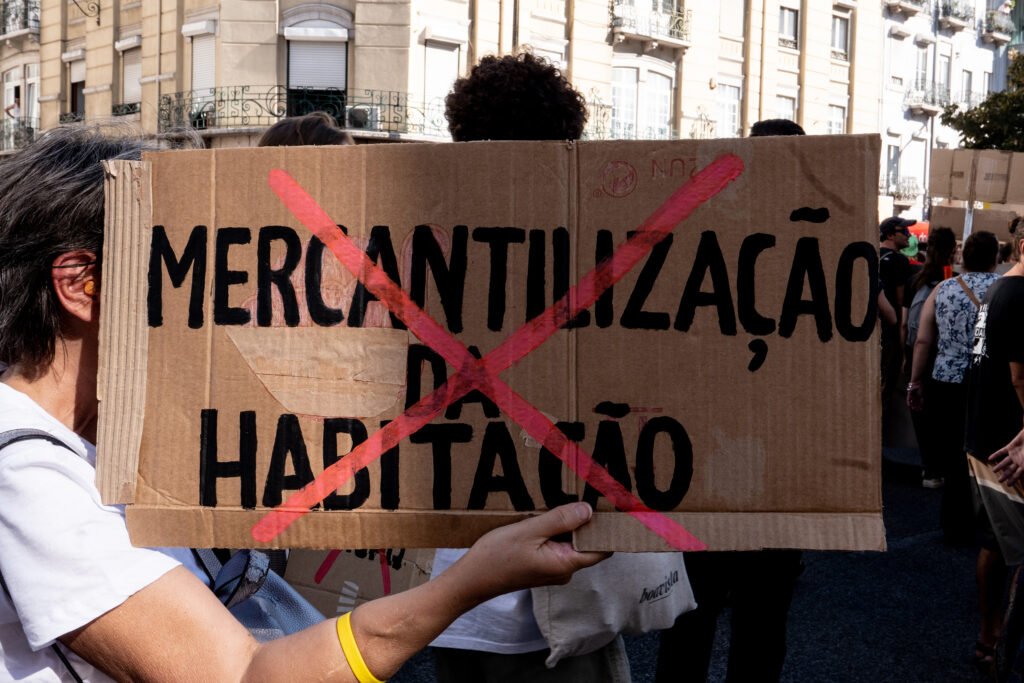

We plainly see how the contradiction of touristification operates: the “charm” of cities is sold as an attraction to be devoured by tourists. Locals are quickly pushed out of the housing market while the mainstream discourse argues that tourism benefits them. Previously rented apartments are transformed into AirBnB units. Where no regulation is set in place, housing rights are squeezed. Responding this increasingly dire situation, a growing movement against the effects of tourism in Mallorca, Malaga, Barcelona, and Lisbon inspires people all over Europe to act in the same direction.

We live a new housing crisis. Prices are once again skyrocketing. Between 2010-2022, housing prices in Europe increased by 48.5 percent. In the same period, the average wage increased by just 29.8 percent. Thus, an average wage buys less and less housing. The working class already paid dearly for the blunders of the financial sector; post-2008 turbo austerity policies linger. And then came the post-pandemic inflation. Now, for most, renting a decent apartment is out of touch, and owning a house is almost a dream—unless inheritance plays a role. In the last decade, wealth became a requirement to access homeownership, making it a “Catch-22”, as urban geographers Cody Hochstenbach and Manuel Aalbers called it. As the two authors point out, “debt continues to be crucial, but it is wealth that is king.” Briefly put, individuals without inter-generational support are less and less likely to access homeownership.

The real estate-financial complex learned its lesson well. As political support for capital accumulation through speculative practices proved unwavering, real estate investment trusts and vulture funds boldly grew bigger and stronger. This has been visible at MIPIM, “the world’s largest real estate market event,” which takes place yearly in Cannes. The figures for its 2024 event are staggering: over 20,000 delegates attended the event, representing more than €4 trillion in assets under management. It is just a rough image signaling the heavy impact of the financial actors and processes on housing production and distribution.

In post-socialist countries, public housing dwindled as privatization policies succeeded. Everywhere else in Europe, political support for public investment in housing projects dropped. The European Union actively worked against the increasing role of member states in public housing production. Dutch private developers complained to the European Commission that the Dutch state’s investment in the public housing sector beyond social housing “distorts the market.” The EC sided with the developers in 2009. But it is more than that. Not only are the EU institutions unequal in terms of deciding over housing policies; the whole EU economic policy framework is designed against the enforcement of housing justice. On the one hand, the free flow of capital, including through real estate investments, is a key principle guiding the EU. On the other hand, public investment in public housing is deterred through monetary and fiscal austerity.

In the ashes of the financial crisis, several housing organizations formed the European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and to the City (EAC), initially as a counter-movement to MIPIM. During its more than ten years of existence, the coalition has served as an international vehicle for people engaged in the fight for the right to housing. Gradually, the number of members grew up to 33, covering 18 countries ranging from Portugal to Romania, and Sweden to Greece. Each member group is formed by people directly affected by housing injustices and their allies. Together they organize, take action, and demand a reorganization of economic and political practices toward the assurance and protection of housing rights.

Moreover, the EAC provides centralized insights into the anatomy of anti-eviction struggles and the workings of financial structures. Since 2020, the coalition has organized annual Housing Action Days. In a ten-day period at the turn of March and April, under the same banner, members and their local allies organize actions suited to their context. More than 130 actions took place in 2024, ranging from street demonstrations to knocking on doors and documentary screenings.

As homeownership becomes increasingly inaccessible, tenant organizing becomes a key direction for social organizing. Organizations from Czech Republic, England, Germany, Ireland, Poland, and Spain are role models: tenant solidarity operates in multiple ways ranging from anti-eviction actions to political organizing for wider changes. The model truly works as a labor union: when a family faces abuse by its landlord, legal or financial support is provided. Moreover, research is quintessential to all these efforts. Each collective provides analyses of housing market policies—how new decisions impact tenants’ wellbeing—while some create inventories of vacant housing.

Education is essential to the advancement of housing rights, this is why for example Barcelona’s Sindicat de Llogateres organized a working group to develop a radical theory on the problem of renting. We are thus moving away from feeling like “temporarily embarrassed homeowners” and acting according to our present material conditions.

There is only one path against incessant dispossession: regrouping and working together to maintain or to gain housing justice. Further, we need to expand our efforts to restructure housing property regimes. At local, national, and EU levels, we have to implement measures to decommodify and definancialize housing. In order to prevent speculative practices, socialist legislation proposes that a household can own just one housing unit. Such an emphasis on the use value of housing, and not on its exchange value, is an inspiring proposition.

George Iulian Zamfir

Sociologist and housing rights activist with Căși Sociale ACUM / Social Housing NOW in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, and currently a facilitator of the European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and to the City.