© Maxim Dondyuk

Ukraine, Kyiv, January 22, 2014.

Protesters carry burning car tires closer to the riot police cordon in the center of Kyiv.

© Diego Ibarra Sanchez for The New York Times

Ukraine, Kyiv, July 16, 2018.

Young Ukrainian boys receive instruction on how to properly don a gas mask at Lider Camp, a hyper-nationalist military summer camp located on the outskirts of Kyiv.

© Christopher Occhicone

Ukraine, Kyiv Oblast, September 6, 2017.

Teenage girls pose for a portrait at the Azovets summer camp.

© Andriy Lomakin

Ukraine, Kyiv, November 29, 2015.

Anastasia, a 22-year-old, combat emergency medical instructor, posing in her apartment with her shotgun, which she bought in November 2015.

© Daniel Carde ZUMA Press

Ukraine, Lviv, March 7, 2022.

“Together we are so strong.”

© Maryna Syrovatka

Slovakia, Bratislava, August 5, 2023.

Anna from Vyshneve.

© Malgorzataa Smieszek

Ukraine, Bystrets, October 7, 2023.

Ninety-two-year-old Anna lived through World War II, the Great Famine and independence movements. Now her children and grandchildren have their own war.

© Hailey Sadler

Georgia, Tbilisi, August 20, 2022.

Thirty-six-year-old Yulia Morozova holds her daughters Masha (14) and Kateryna (3). She says her children have been clinging to her more since leaving home back in April. They want to be near her, touching her, whenever they can.

© Oksana Parafeniuk

Ukraine, Kyiv, August 5, 2022.

Oksana Parafeniuk and Brendan Hoffman’s newborn child, Luka.

© Carol Guzy for NPR

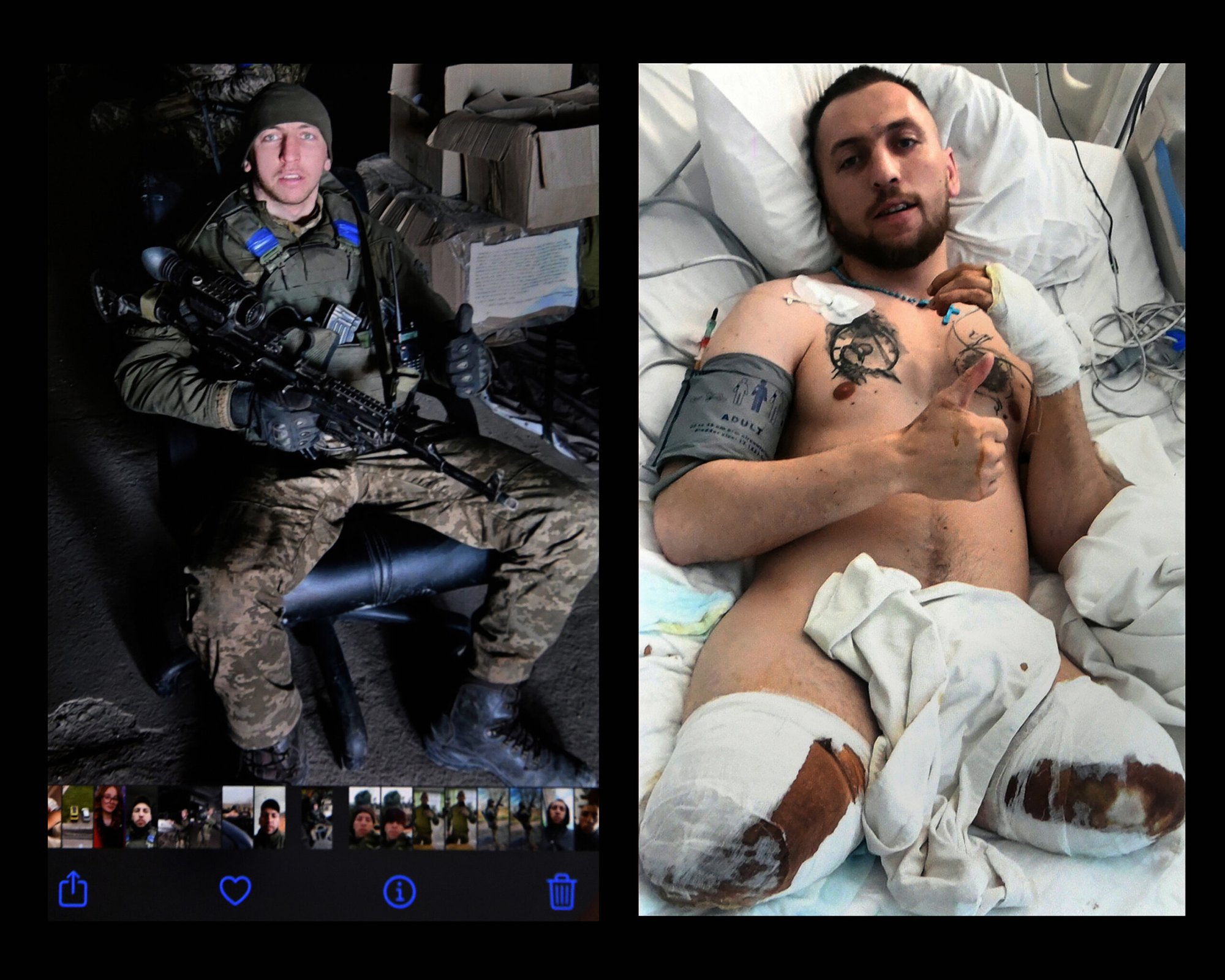

Ukraine, Truskavets, November 9, 2022.

During frequent air raid sirens at the hospital in Truskavets, Misha yearningly looks at cell phone photos of himself in battle fatigues. He constantly shows pictures of their previous daily life, including raw images from when his legs were first amputated. “Look at this grayness – weekdays of nothing. There it was real life,” declares Misha about fighting the war.

© Celestino Arce

Ukraine, Kherson, June 11, 2023

© Paula Bronstein

Donetsk region, Yasne, July 4, 2018

© Evgeniy Maloletka

Ukraine, Kyiv,February 15, 2024.

Maria Lezhnova, 52, sits with her pets, waiting for her son Hryhorii Polevyi, a 29-year old, medic with the 120th Battalion, who went missing at the frontline in Mayorsk, in the Donetsk Region, on November 4, 2022, along with ten others. The day before he vanished, he sent a message saying, “Love you very much, I will go without connection for some time.”

- As of summer 2024, it is estimated that around 45,000 women have voluntarily joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine. ↩︎