Cover photo: A Kurdish woman during a demonstration in Paris in January 2014, standing in solidarity with her community and highlighting their ongoing struggles. © Maryam Ashrafi

A recent series of deadly drone strikes in Iraqi Kurdistan has highlighted Turkey’s willingness to destabilize the region in its pursuit of eradicating the Kurdish liberation movement. On September 5, a Turkish drone killed three civilians, including a child. This attack followed a similar incident the day before, which killed a father and his two teenage sons.

Perhaps most seriously, on August 23, two Kurdish women journalists, Gulîstan Tara, and Hêro Bahadîn, were killed by a Turkish drone strike while traveling in a car on the outskirts of Suleimani. The two journalists were on assignment for Chatir Media Company. Six others were injured in the attack. The reporters’ deaths have sparked widespread international reaction, including strong condemnation from local and international media advocacy groups.

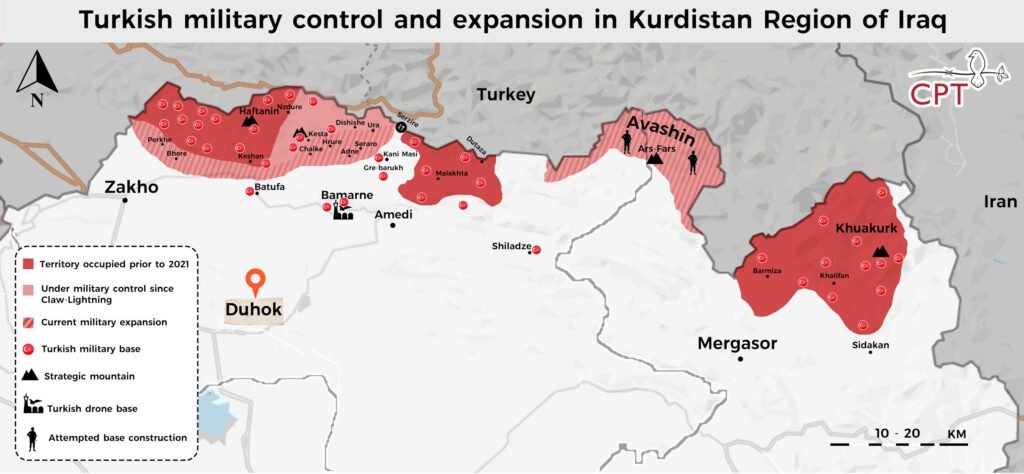

Such attacks are just the tip of the iceberg of Turkey’s action plan. According to the international human rights organization Community Peacemaker Teams (CPT), Turkey has carried out more than 800 attacks in the region this year alone while putting over 600 villages at immediate risk of depopulation through a ground invasion.

The recent wave of violence adds to a decade-old design aimed at eliminating Kurdish political autonomy. To achieve its goals, Turkey has used extensive military, geopolitical, and diplomatic means beyond its borders.

A Decade of Extermination War

In 2014 Autumn, the Turkish government set up a new strategy for targeting the Kurdish political movement, known as the “Collapse Strategy” (Diz Çöktürme, literally Kneeling Down). As the name suggests, the state aimed to subdue all organized Kurdish structures and prevent any future movements in the name of Kurdish identity. The Turkish National Security Council approved this strategy on September 30, 2014. It is important to emphasize that at that time, Ankara had ongoing peace negotiations with the Kurdish Liberation Movement, including meetings between the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) delegation and jailed Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan, held in solitary confinement on İmralı Prison Island since 1999.

The Collapse Strategy reveals that during the negotiations, the Turkish state had no intention of reaching reconciliation or peace with the Kurds. Instead, the state chose to engage in dialogue as a tactical move in response to the political climate at the time. The two-year dialogue period was used to prepare for a more aggressive approach towards the Kurds. The state began implementing its strategy when the Kurdish movement achieved significant results in the 2015 general election that could change Turkish politics. Talks with Öcalan were cut off, snap elections were called, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s regime sought to seize all state institutions.

However, the internal power struggle between the Turkish power factions partially delayed this process. After the attempted military coup in July 2016, everything was redesigned: the authorities declared a nationwide state of emergency, and an all-out war against the Kurds commenced. Since then, Turkey has deployed a broad range of military, diplomatic, and geostrategic tactics as part of its efforts to undermine the Kurdish movement by any means necessary.

Until today, Ankara’s perspective on the Kurdish issue has remained unchanged: it is viewed as a “terror problem” that cannot be suppressed solely through military operations within Turkey’s borders. The existence of Syrian and Iraqi Kurdistan will always pose a “national security threat” to Turkey because the Kurds could reorganize by relying on these regions. Therefore, Ankara decided to carry out military operations beyond its borders. Although there had been similar attacks in the past, this time the government made a more permanent decision. Security operations were also launched internally against the Kurdish political movement to suppress potential social and political reactions, with 10,000 political figures, including former HDP leader Selahattin Demirtaş and his colleagues being arrested or removed from politics.

The plans of Erdoğan and his cabinet extended beyond these actions. By occupying various regions in Syria, they aimed both to block the Kurds and to strengthen their hand against the Syrian regime. Ankara sought to change the demographic structure of Kurdish regions by invading and establishing settlements in Syria through Jihadist organizations such as the Muslim Brotherhood. Furthermore, by occupying key locations in Iraqi Kurdistan, their objective was to exert influence on the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) and gain control over the highly sought-after Mosul-Kirkuk axis. To make this a permanent plan, the Ankara regime openly declared its intention to create buffer zones extending 30 to 40 kilometers deep into Iraq and Syria. In reality, this move, carried out under the guise of “counter-terrorism,” aimed at effectively annexing these two parts of Kurdistan to Turkey.

In 2019, at the 74th United Nations General Assembly, Erdoğan illustrated his plan for Syria: the Turkish army would carry out a military occupation from the Mediterranean—where Afrin (Efrîn), a Kurdish city in northwest Syria, is located—to the Iranian border. And then, by permanently occupying this area, alter its demographic composition.

Three years earlier, in October 2016, the Turkish state launched simultaneous attacks in Syria. These offensives have gone through various stages and continue to this day. In northern Syria, the cities of Afrin (Efrîn), Tel Abyad (Gire Spî), and Ras al-Ayn (Serê Kanîye) were successively occupied in 2018 and 2019. Indiscriminate bombings, aerial attacks, and assassinations are still ongoing.

In the meantime, the attacks on Iraqi Kurdistan continue in a much more severe and systematic manner. The Turkish state has given these attacks a strategic objective: to eradicate the guerrilla movement that has taken sanctuary in the mountains for more than 40 years of insurgency officially declared on August 15, 1984, by attacks military bases in three towns in Turkey’s Kurdish majority South East. Not only did Turkey take this step, but it also made changes to its war strategy.

A New Alliance: The Barzani Dynasty Moved Closer to Turkey

Firstly, the war concept was altered. Politically and militarily, Turkey allied with Iraqi Kurdistan’s dominant Barzani family. Furthermore, the state introduced new technologies to gain superiority on the battlefield. It planned to control the terrain using reconnaissance aircraft that were later also armed to intervene immediately when detecting movements on the ground. Taking advantage of this, Ankara heavily bombarded targeted areas, almost reshaping the landscape, burning forests, and destroying the soil. Protected by reconnaissance planes, ground troops started marching to these regions and established permanent settlements wherever possible. These outposts were strengthened with technology to secure control of the terrain in certain areas.

On the other hand, the alliance with the Barzanis ruling elite had several advantages. Military units loyal to the Barzanis took control of potential routes and strategic points that guerrillas could use, trying to cut off their supply lines and connections between the different areas. These units fulfilled various functions, including providing instant intelligence to the Turkish army.

The Barzanis’ mission included both military and political calculations. As we have summarised above, the strategic goal of the Turkish state is to suppress the organized Kurdish movement. Naturally, they would not openly declare it. Turkey tried to conceal the operation against all Kurds by allying with the Barzanis, who welcomed this alliance for their narrow familial and regional interests. For the Kurdish clan, serving Turkey was more profitable than associating with other Kurdish parties. The clan became a de facto instrument for Turkey.

To better understand the Barzanis, their mission, and this alliance with Turkey, it is essential to delve into their historical background. The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), currently controlled by the Barzanis, was founded in 1946 by Kurdish intellectuals in Iraq. At the time, the Kurdish Republic of Mahabad in Iran had collapsed, and Mullah Mustafa Barzani, Mesud Barzani’s father, had taken refuge in Russia. In 1958, Mullah Mustafa returned to Iraq, taking control of the KDP. The Barzani family acted against other Kurdish organizations to establish good relations with regional states. They collaborated with Iran in the 1980s, and now they are cooperating with Turkey. The Barzani family is more aligned with the perspective of political Islam than with Kurdish identity, and it is primarily based on the monarchical system of regional countries. As a family dynasty currently controlling Kurdish gains in Iraq, they serve Erdoğan’s regime to maintain this dynasty. In turn, Erdoğan keeps them close to use them against the Kurds.

New Methods of Resistance: The Kurdistan Workers’ Party Moved Underground

The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) has taken note of these new developments and has implemented countermeasures. PKK Executive Committee Member Murat Karayılan recently stated that, in the autumn of 2016, he met twice with the Barzanis and KDP. However, these talks did not yield any results. The PKK likely aimed to ensure that the Barzanis would at least remain neutral in this new process. Karayılan had conveyed the same appeal to the Barzanis in earlier statements.

In recent years, the PKK has made significant changes on the battlefield. As a guerrilla movement, the PKK was not using terrain-holding tactics against regular armies. The conditions compelled new strategies and tactics to respond on the field, in the air, and underground. Notably, to nullify Turkey’s air superiority, the PKK went underground. Guerrillas built war tunnels and underground living spaces, almost creating a new mountain under every mountain. Living underground provided an extraordinary advantage for the guerrillas, rendering many of the Turkish army’s technical devices ineffective. Turkish soldiers, lacking the capability and experience for underground warfare, encountered an unexpected situation.

Turkey planned to occupy all the targeted areas by 2023 and close this “chapter” by the 100th anniversary of the Republic of Turkey. However, by 2022, the Turkish military intelligence realized it was impossible. Ankara introduced new tactics, such as the use of chemical weapons in the guerrilla tunnels. In the autumn of the same year, tensions escalated, and Turkish troops were deployed around strategic villages and towns in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region through the KDP. They planned direct attacks on guerrilla areas to establish wider territorial control. However, they also assaulted villages to depopulate the region. According to reports from independent civil society organizations, so far 200 villages have been evacuated. Currently, the evacuation of 602 more villages is planned. These attacks have resulted in tens of thousands of people being displaced from their homes, as many civilians have been killed. Civil society organizations have documented the attacks against civilians.

The PKK guerrillas developed new tools in response to these renewed attacks. They did not confine themselves to tunnels alone. Starting from February 2022, Turkey’s much-praised unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) were shot down. According to statements by PKK’s military wing, the People’s Defense Forces (HPG), in one year, they shot down 19 UCAVs. HPG published footage of all the incidents to prove it. For the Turkish state, it was a shock as its most trusted weapons could no longer be sent to the war zone. PKK guerrillas, not stopping there, began sending kamikaze drones to Turkish military positions and publishing footage of these attacks.

These developments changed the course of the war. In response, Turkish troops moved closer to civilian-populated areas, deployed warplanes more intensively, and built concrete bunkers to protect themselves. Despite all these developments, the Turkish state sought new strategies to achieve its objectives.

A New Agreement: Regional States and the Kurdish Question

Ankara realized that its goals could not be achieved solely through the ongoing attacks and the support of the KDP. Therefore, it attempted to involve another faction in the KRI, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), in the war, but this did not yield results either. Moving forward, Ankara opened negotiations with both Iraq and Iran. Due to the wider developments in the region, Tehran did not want to confront Turkey or the Kurds directly. While not directly participating in Turkey’s attacks, Iran directed its affiliated “Hashd al-Shaabi” militias in Iraq (also known as Popular Mobilization Forces) towards Ankara. The Iranian regime also saw Turkey’s extensive involvement in Iraq as a strategic threat, so it had to manage this process carefully. As a result, Iran responded negatively to the Turkish army’s attacks on areas close to its borders.

However, Ankara’s initiatives with Baghdad were partially successful. Using water and various trade agreements as leverage, Ankara signed a deal with Iraq’s Sudani government on August 15, 2024. The date was not chosen by chance, as it marked the 40th anniversary of the PKK’s commencement of armed struggle. Among those signing the agreement on behalf of Iraq were Fuad Hussein, Iraq’s Foreign Minister and a close aide to the Barzanis.

Over the past century, states in the region signed several similar agreements against the Kurds. The most striking is the Sadabad Pact, signed in Tehran, Iran, on July 8, 1937. Afghanistan, Turkey, Iran, and Iraq signed this agreement. Article 7 of the treaty directly targeted the Kurds to break and suppress any organizations formed by the Kurds living on both sides of the Turkey-Iran, Turkey-Iraq, and Iran-Iraq borders or any support they could provide to each other.

Iran was not directly involved in the latest agreement signed between Iraq and Turkey on August 15, but there were forces linked to Iran. What is new in this agreement is the inclusion of a “Kurdish” party. Thus, a multilateral agreement, like the Sadabad Pact, led to new problems rather than suppressing the Kurdish issue. The fate of the August 15 agreement will likely be similar.

In the meantime, the Sudani government has approved attacks by Turkey targeting the PKK within Iraq’s borders. However, many factions in Baghdad are dissatisfied with this situation. Indeed, the Turkish drone shot down in Kirkuk on August 29 can be seen as a message from these factions to Ankara and the Sudani government. Yes, an agreement was signed, and the PKK was banned in Iraq, giving legitimacy to Turkey’s attacks. However, this has not been a game-changing move for Ankara and will not be. On the contrary, it may cost some political elites in Baghdad, who facilitated this agreement, their political careers. It will be more apparent in the Iraqi parliamentary election next year.

Nonetheless, the agreement has opened a new door for Turkey. The Turkish state will play a more active role in Erbil and Baghdad. It can intensify intelligence and military activities in its military bases near Mosul. At the same time, it will continue to threaten the Yazidi region of Sinjar as well as the Gare Mountain, a PKK stronghold. It will continue to provide paramilitary training to its allied Turkmen militias near the Mosul-Kirkuk axis and carry out some military actions through these groups.

The question of what the PKK will do in response is becoming more critical. On August 15, Murat Karayılan, who is also the commander of the People’s Defence Headquarters of the PKK’s military wing, released a video message declaring the guerrillas would resist Turkey’s attacks using all types of war vehicles on land, in the air, and underground.

During this autumn and winter, there can likely be intense fighting. Turkey can try to accelerate its attacks based on its agreement with Baghdad and the volatile situation in the region. On the other hand, the guerrillas will resist by taking advantage of the seasonal conditions—such as decreased mobility and visibility— and using their newly developed technological tools. It will not be surprising to see heavy counter-attacks against Turkish soldiers in the region.

The Way Forward: International Players Must Choose a Constructive Approach

So, where will this situation lead? The Turkish state signals that it does not abandon its strategic objectives. Although the severe economic crisis and the political bankruptcy of the Erdoğan regime are obstacles for the state, the method of suppressing the Kurds through war has been given more emphasis. The Erdoğan regime views its insistence on war as an opportunity to consolidate its power. The anti-Kurd stance uniting all political factions is Erdoğan’s greatest advantage, as heavy attacks against the Kurds can be used to consolidate his supporters and nationalist factions.

On the other hand, Kurdish resistance will definitely shape the course of this process. Opposition against the Erdoğan regime could push the state into deeper crises and in turn force a shift in its strategy. In either scenario, a heavy and costly process awaits. The state can continue to suppress and eliminate political opponents, while the Kurds will continue to resist and survive.

At this point, the position of international powers is also essential. Despite the severe attacks, civilian massacres, and the use of prohibited weapons, there has been no intervention by global powers and institutions so far. Turkey has committed war crimes in front of the international community. It has used and continues to use NATO weapons against the Kurds. On the other hand, with Russian support, it tries to prevent a potential Kurdish status in Syria. Turkey has used every possible means against the Kurds, exploiting the contradictions between these powers, as well as the Ukraine and Israel-Hamas conflicts.

These powers find it in their interest to support Turkey against the Kurds, and they maintain this stance. Thus, we see again that human rights and democratic values are interpreted according to their interests. The Erdoğan regime also uses this situation to maintain its existence. The Kurds, having endured this situation at a significant cost, will continue to organize and resist to survive. From this perspective, even more challenging times lie ahead for the Kurds and the region.

The EU and the US have not helped to solve the problem but instead deepened it by placing the PKK on the “terror list.” The PKK is a result of the denial and destruction policy that the Turkish state has pursued against the Kurdish people for a century; it is not a cause. By listing the PKK as a cause and placing it on the “terror list,” the Western powers have supported the Turkish state’s denial and destruction policy, and they continue to do so. With this position, they have become complicit in the oppression of the Kurds. Indeed, the Belgian High Court ruled in recent years that the PKK is not a terrorist organization but a party in an armed conflict. The European Court of Justice has also made similar rulings. What needs to be done, first of all, is to remove the PKK from this list to correct the injustice against the Kurdish people and encourage a political solution. All other policies can only serve as tools for the annihilation of a people.

A New Peace Process on the Top Agenda of Turkish Politics

Since October 1, 2024, very interesting political developments have been taking place in Turkey’s power circles. Apparently, the Turkish regime is no longer able to continue the existing war according to the collapse doctrine they developed in the fall of 2014. Therefore, due to the influence of the changing international power conjuncture, some sorts of preparations are being made for a controlled transition to democracy. Peace with the Kurds, a new democratic constitution, and solving problems through dialogue and political methods rather than violence have become the most used concepts in the last two weeks by the ruling elites of Erdogan’s regime.

To briefly summarize recent developments, Devlet Bahçeli, the leader of the ultra-nationalist partner of the current government reached out to the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party Party (DEM Party) members in the parliament, shook their hands, and wished them success in the new legislative year. This behavior was very unusual. Until now, he had been only calling for the DEM Party to be dissolved, its members to be arrested, and the municipalities they had won to be “trustee-appointed.”

Likewise, in his political speeches over the last two weeks, Erdoğan has repeatedly emphasized the importance of education in mother tongue and the establishment of a democratic regime.

At the time of writing this article, a redesigned negotiation process with the Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan, who has been kept in a state of non-communication since April 2015, has become the main agenda of daily politics. The reasons why the peace talks between 2013 and 2015 failed are frequently discussed, and the need for a new negotiation process in a special format, learning from the lessons of the past, has become the main topic of daily politics.

On the other hand, the Kurdish side, especially the PKK executives and the DEM Party co-chairs, are quite cautious and have distanced themselves from these new discourses. They emphasize the importance of the messages Öcalan can deliver to the public and call for the lifting of his absolute isolation as the most important reassuring step.

Instead of a clear-cut conclusion, the following observations can be made with clarity at this point. The Turkish state has reached the end of the Collapse Strategy, which it has been pursuing for the last ten years. The Kurdish people have frustrated this doctrine with its widespread and organized resistance. Turkey, which is allied with the institutions of the international Western community, such as the EU, the European Council, and NATO, has been experiencing contradictions with them at the highest level in the last decade. Economically, Turkey is in the worst period of its history. In these days of escalating Middle East wars and conflicts, with a possible Israeli attack on Iran and its supporting organizations and countries, it is understood that Turkey is planning a rapid transition to democracy. It is obvious that this can only be achieved if the war against the Kurdish Freedom Movement ends, and the Kurdish national existence is officially recognized in the new prospect of a democratic constitution.

Sinan Önal

Sinan Önal is a political scientist, currently an envoy of the Kurdistan National Congress who formerly acted as an adviser in policy-building and international affairs to the left-wing alternative and pro-Kurdish parties DTP, BDP, and HDP in Turkey. Mr. Önal also represented the pro-Kurdish party in the United States in 2012-2013, and in Germany in 2017-2018. He is also a columnist in the MedyaNews online venture.