Women Photographing Conflict:

The First Rough Draft of History. Or Herstory. Or The Story.

by Lauren Walsh

March 12, 2025

Journalism is the first rough draft of history – so the saying goes. But who wrote that draft? Who held the pen…or the microphone, the camera, the recorder? For much of history, the majority of that first rough draft was authored by men. And photographed by men.

As Daniella Zalcman, founder of Women Photograph, a non-profit established to elevate the work of women and non-binary visual journalists, said in 2023: “This business [of photojournalism] has been dominated by the white, Western male gaze for its entire existence, and that has a huge impact on how we determine what deserves to be documented in newspapers or history textbooks. It’s urgent that gatekeepers encourage, mentor, and support photographers who can bring other experiences and ways of seeing to the table.”

To be fair, there have always been exceptions, the dedicated women who forged a professional path, going against the industry grain. In fact, the Instagram account called TrailblazersOfLight highlights such pioneering women, recognizing and celebrating their photographic achievements, so their names and work are never swept aside with an offhand “this has always been a male industry” critique.

Even so, the fact remains that societal norms and institutional biases have resulted in staggering gender imbalances over the years. To this day, there is still global gender inequality in photojournalism, and such imbalances become starker in the field of war correspondence.

As Joumana El Zein Khoury, the Executive Director of World Press Photo, observed in January of this year, “the media organisations that covered the war held a power structure that controlled not only what pictures were seen as important, but who took, edited and published them.” El Zein Khoury was responding to a debate about an iconic photograph from the Vietnam War, but the fundamental principle holds broadly for war reportage: There have been power structures baked into the industry, and women and non-white practitioners were so often without equal agency, authority, and acknowledgement.

Accordingly, this essay reframes that dynamic, examining the contributions of female photographers, many of them non-white documentarians. In so doing, I explore the risks and challenges, rewards and ingenuities of these intrepid women who photograph conflict. But let me pause a moment to note that I am careful to choose the term conflict in place of war. To my ear, the latter delimits the field to coverage of armed fighting between nations, states, or groups. Whereas conflict, by contrast, is the looser, broader term that folds in many kinds of hostile environments and situations, including natural disasters, explosive riots, gender-based violence, mass atrocity, and state oppression, to name a few such scenarios.

Not long ago, the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) released its 2024 report, which surveyed hundreds of American journalists on the threats, harassments, and attacks they face in their line of work. Over one third reported issues of physical violence; one third described threats or experience of digital violence; over a quarter reported legal threats if not action against them; and 24% experienced sexual harassment. In particular, the report details: “Overall, women journalists, particularly photojournalists and those working in the field alone, described sexual harassment as a routine part of their work, and consequently of their safety calculus.” Moreover, the IWMF findings reveal, “Every photojournalist interviewed experienced physical threats and harm while reporting.” And this is just in the U.S., which ranks at 55 out of 180 on the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index. Imagine the threats, challenges, obstacles and dangers in countries with worse rankings.

Meanwhile, the Committee to Protect Journalists’ year-end 2024 report outlines risks faced around the world, highlighting the threat of imprisonment. According to the CPJ prison census, 361 media workers were incarcerated at the end of last year, the second-highest detainment figure in the organization’s history.

Other recent research reveals that the hazards go well beyond bodily injury and incarceration. Consequences for mental health have also been severe, as my own ongoing work in Ukraine underscores. A nationwide survey I designed, with support from Daily Humanity Foundation, rolled out in fall 2024. Data is currently being collated and analyzed, but preliminary findings indicate significant levels of depression, burnout, stress, and anxiety across the broad Ukrainian media sector, with close to 90% of journalists saying they have experienced a traumatic episode and around 10% having thoughts of suicide. The results of that survey will afford an accurate, contemporary picture of in-country journalists’ psychological status and their needs; and ultimately, the data will inform support programs, to provide a safer, more sustainable work environment.

In short, the challenges of working in Ukraine, or any locale that constitutes a hostile environment, are many. So why do photojournalists do it? What motivates their work? What are their hopes, their successes, and failures?

The following represents the voices of a few women around the globe who have picked up their cameras and documented a variety of forms of conflict. Each brings small glimpses into singular aspects of this work—whether a challenge, a triumph, a goal, a hardship, or an aspiration. They are all, like that Instagram account I referenced, trailblazers in their own right.

Fatima Tuj Johora, based in Dhaka, Bangladesh, describes the moment that she committed herself to this profession: “Initially I wasn’t sure where I fit within the world of photography. But the day I witnessed a devastating fire in a nearby slum changed everything. Balancing the act of capturing the moment while witnessing the suffering of those affected was challenging, but it also solidified my desire to document reality and share untold stories.”

In July of last year, Bangladesh erupted in riots, largely led by students demanding political reform and an end to governmental corruption. The response from authorities was swift and violent—and in violation of human rights, with unlawful use of force. According to Amnesty International, in a ten-day window, more than 200 people were killed. Meanwhile, the government imposed a communications blackout, taking the country offline and seemingly rendering abuses invisible.

Terrible violations can occur in the cloak of darkness, and the work of visual journalists, like Tuj Johora, is vital.

“There were many obstacles to overcome, but convincing others to allow me to do my job was the most significant challenge during that time. We were at risk of attack from the protestors, the government party, and the security forces. For them, that was typical because the media could not satisfy all of their needs. It was a very volatile and unmanageable situation,” Tuj Johora explains.

She adds, “The internet outage made it difficult to work while keeping up with the situation. News gathering, understanding situations, making plans without knowing what was happening all over the country were so difficult without an internet connection. Covering that without any safety equipment and without prior [hostile environment] training was, of course, difficult. Journalists were sometimes targeted for attack, so at times I pretended not to be a journalist while getting back to my home from the field.”

As Tuj Johora notes, safety trainings and protective equipment (like helmets for volatile settings that may include projectiles) are not guaranteed to journalists even though they may face serious physical, emotional, reputational, legal and/or online threats. Add to this the fact that photographers can never work remotely—they must be on site to witness and document—and one begins to understand how risky this work can be, and how vital safety awareness and support are.

Despite such obstacles, Tuj Johora continues her work. “Ultimately, what drives me is the desire to tell impactful stories that resonate, provoke thought, and shed light on the human experience.”

Samar Abu Elouf, a Palestinian photographer who had been based in Gaza City, covered the recent destruction by Israel inside of Gaza. She has escaped and here reflects on what she hopes a broad public understands when looking at her photographs.

“I want people to learn from my pictures. I convey the truth as it is on the ground, without any change or falsification. I want people to be more humane in dealing with others. We all have dreams and ambitions. And these are people in the pictures. These are not just pictures. They are human beings who feel and wish to live in safety, security, and peace.”

As of this writing, nearly 50,000 people, most of them civilians in Gaza, have been killed. This includes, per CPJ, at least 170 media workers.

Of her deep connection to the individuals she photographs, Abu Elouf says, “I am part of this society and I want the world to know us.” She advocates for a common humanity in the viewing audience.

At the same time, Abu Elouf acknowledges that “pictures alone are not enough” to resolve this crisis. Photographs advance knowledge and can engender emotional reactions. But the burden cannot be fully on the photographer to communicate the entirety of a situation. That is an impossible expectation, and a reality that the news consuming public should understand.

Amat AL-Rahman Alafory is a Yemeni photographer. She describes the situation in her homeland: “The conflict in Yemen is very complex; it is not merely a dispute between two parties, but a harsh political struggle among three authorities with different orientations and goals. This makes us as journalists pay the price for every word we write or report we publish.”

“There are severe restrictions,” she adds, “particularly on independent, female journalists, making coverage nearly impossible and fraught with danger at times.”

In December 2024, UNICEF reported: “Yemen continues to face multiple crises, including ongoing conflict, economic insecurity, widespread malnutrition, a fragile healthcare system, and recurrent disease outbreaks, all of which compound one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world.”

Of her own experiences as a local visual journalist, AL-Raman Alafory describes difficulties and directed repression. “On a personal level, I have been living in a state of forced separation from my family for eight years, even though we are in the same country. My family lives in areas controlled by the Houthis, while I live in Aden under the control of the legitimate government and the de facto authority, the Southern Transitional Council [a secessionist organization in southern Yemen].”

AL-Raman Alafory continues, “I have faced many harassments: some of my equipment was broken, my bags have been searched, and my personal ID card has been confiscated, yet I have always sought solutions that I cannot disclose at the moment [due to security precautions].”

“Moreover, I have faced threats due to my coverage of sensitive issues, such as cases of enforced disappearances,” AL-Raman Alafory shares. “I have been accused of belonging to a terrorist group, as [the ruling powers] claimed, and I received direct threats through comments on my Facebook posts and messages via WhatsApp from unknown numbers. Even my social media accounts were completely hacked, and I had to create a new account on Instagram after losing control of the previous one.”

AL-Raman Alafory was even forced by authorities “to sign a written commitment not to engage in fieldwork.” This, of course, is censorship – at the extreme level of threatening and controlling journalistic endeavor. It has, she says, “led to [a] complete cessation of work until now.”

If the tolls seem so dire, why continue with this profession? AL-Raman Alafory has considered this. Ultimately, she believes in the fundamental role of journalism: “I am the only female field journalist in Aden. I have been very close to the community, which has helped me build extensive relationships that allow me to access sensitive stories that would not have been possible to cover or reach without those supportive factors. I believe that a journalist should be the voice of the citizens, especially at times when they need to convey their suffering.”

“I know there are risks, and our society is still not accepting of women’s work, especially in journalism and media,” states AL-Raman Alafory with gravitas, “but I feel a professional responsibility that compels me to convey the truth.”

Arlette Bashizi is a photojournalist based in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where she has been working and covering conflict since 2018.

“The stories that retain my attention,” she says, “are usually related to women and youth. For instance, I use my camera to share stories of displaced women and how this conflict is impacting them.”

The reality is Bashizi never aspired to be a conflict photographer. “When you’re born in a country affected by conflict for more than two decades, you don’t have a choice. It’s our responsibility as Congolese photographers to document both sides of the story: the local initiative as a response to this conflict but also to document the conflict’s consequences for civilians. I want viewers to not forget the ongoing conflict in Congo and its impact here. Not talking about it will keep this crisis forgotten by the rest of the world.”

International organizations echo Bashizi’s concern. The Norwegian Refugee Council has described this pressing crisis as “ignored,” while others have characterized DRC as “forgotten.” Yet in January of this year, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) quoted a Deputy Relief Chief saying that the “scale of suffering in DR Congo demands urgent attention.”

Prioritizing what motivates her commitment, Bashizi notes, “I have had the opportunity to work with great editors and colleagues, who care and support me emotionally and offer advice, and that helps me to keep going.” She adds, “I have also received protective gear from Reuters [news agency], and training in safety so in terms of resources I am well equipped.”

As Bashizi has observed, her work serves an important role, yet she simultaneously struggles with the larger, international media ecosystem that often doesn’t pay attention to the crises in DRC, at times rendering this situation invisible. “Sometimes I feel powerless,” she says. But, in the end, Bashizi believes in the work: “I feel fulfilled by every single story I am able to tell because I contribute to raising the voices of people I photograph.”

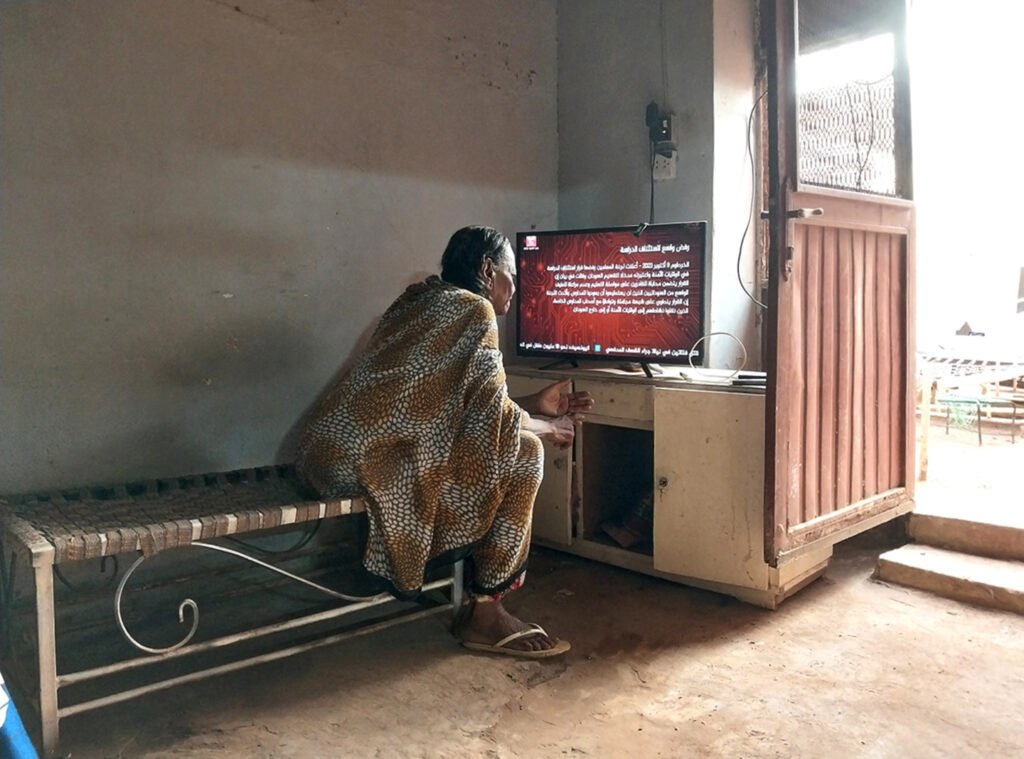

Aya Sinada is a Sudanese photographer whose coverage addresses the intersections of environment, economy, war, education, and health. “In my reports, I focus on exploring the mutual impact of these factors on people’s daily lives amidst the conflict.”

In April 2023, Sudan’s current civil war erupted, and per the International Rescue Committee (IRC), 14.6 million people are displaced and 30.4 million (more than half of the country’s population) require humanitarian support. The IRC, among others, has observed: “Sudan now represents the largest and fastest displacement crisis in the world. It is also the largest humanitarian crisis on record.”

Yet as Sinada states, “My aim through my work is to shed light on human stories that are often untold in the context of conflicts, highlighting the human dimensions of the war beyond mere numbers and statistics.”

She also describes how this environment affects her work. “The ongoing humanitarian crisis and conflict have significantly impacted my work as a photographer. I lost my entire archive and all my equipment, which was a devastating blow. My only tool for documentation became my mobile phone, and I lived in constant fear of losing it as well. Despite these challenges, I tried to adapt by using whatever means were available to document people’s suffering and stories of displacement.”

Like Bashizi, Sinada never set out to be a conflict photographer. “I used to consider myself a visual artist, but these current events pushed me to venture into photojournalism.” She adds, “For me, it was the least I could do in the face of war and my inability to contribute in any other way or express myself in any other form than through journalism.”

On the risks this work entails, Sinada explains, “Being a woman made working in conflict zones, or even in relatively safer areas I operated in, extremely dangerous. A single secretly taken photo could lead to arrest or even death. Therefore, I had to take every precaution before capturing any image to ensure my safety.”

She elaborates, “I use my phone camera for most of my photos, along with written reports, because it is easier to conceal and allows me to work without facing questioning. As for why I chose photography over other forms of expression, it is because I didn’t have access to a computer, making the cellphone camera my only available tool for documenting what was happening. I don’t own professional camera gear and receive no technical or professional support from the magazine where I publish, apart from the financial payment for the reports.”

Crucially, Sinada discloses, “There is also no form of emotional support, which I deeply miss given the immense pressures faced by those working in this field.” Lack of emotional support is endemic in this broader industry, and is a gap that needs to be acknowledged, addressed, and corrected.

Julia Kochetova echoes both Bashizi and Sinada in how she came to be a war photographer. She didn’t seek it out; the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia brought war to her home. She reflects on that: “This war already affected me and it’s going to affect me for decades, no matter when it ends; it will affect me throughout my lifetime.” Kochetova has worked throughout the country, documenting both military and civilian experiences.

As a Ukrainian photojournalist, Kochetova highlights differences between local and foreign correspondents.

“These foreign journalists were coming here and photographing, and re-traumatizing our people. They don’t realize what they leave behind. The trauma. For us, it’s such a personal story. It is always going to stay a personal story. I remember thinking in the first months, like in March 2022, ‘All my female friends left. All my male friends joined the army. Now I have this foreign bubble around me. What the hell should I do?’”

Kochetova adds, “We have additional trauma to deal with, concerns that would never be a question for a foreign journalist. Should you join the army or continue making pictures? Should I be a combat medic or continue making pictures? Should I be a volunteer, evacuating people from the hotspots? These questions never stress the heart of the foreign reporter.”

“For me, at least, as a female, I could leave the country whenever I want,” says Kochetova, referring to the ban on travel for Ukrainian men of conscription age. But, she asserts, “in my head that was never an option.”

Cover photo: *A protester is seen blocking a police van as the police detain activists during a demonstration outside the High Court building, where protesters are demanding justice for those who were arrested or killed during the countrywide violence. Dhaka, Bangladesh, July 31, 2024. Bangladesh’s government called for a day of mourning on July 30 for victims of violence in the nationwide unrest, but students denounced the gesture and said that it was disrespectful to their classmates who were killed during the clashes with police this month, so they held a “March for Justice.”