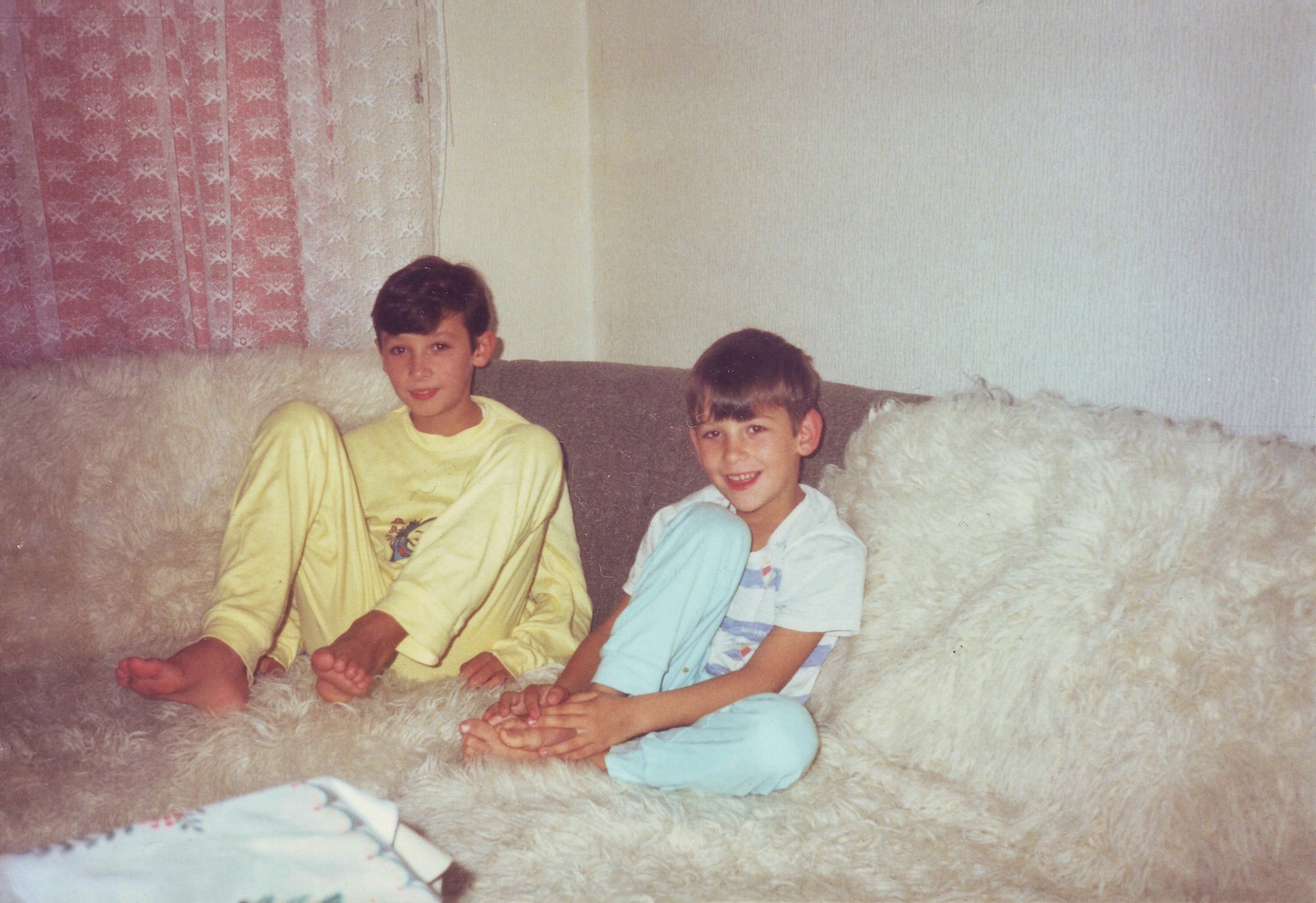

Cover photo: Amel (in yellow pajamas) and Džemil before the war, ca. 1991. Photo courtesy of a private collection / Sniper Alley Photo

My friend once said, “I’m not alone in this, but one in thousands of broken ones and yet unbreakable.” I feel the same as a survivor and a witness of a war. No, I am not a victim, even though some people would describe me as such. We who experienced the Siege of Sarajevo and Genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina, we are survivors.

The story of me and my family is just one among many, if not of everyone, in my country where for 30 years we are reminded of unpunished war crimes and atrocities we experienced, but also denialism, while dealing with the consequences of the war. On a daily basis. And we all deal with our pains differently. Nobody can do that for us. To bear with it, we have to end the role of eternal victims, dry our tears, and keep on fighting for our memories and loved ones once who we lost.

I have these chocolate wrappers that I’ve been keeping since the day my brother was killed. It was a truce, a sunny summer morning and we had our breakfast together. After we finished, we shared these chocolates as siblings usually do. It was our very last time to share something. It was May 3, 1995, and that was our last moment together before he was killed by a sniper.

I was 12 and Amel was 16 at the time. The person who killed him was under the command of Dragomir Milošević, the head of the Sarajevo-Romanija Corps of the Army of Republika Srpska from August 1994 until the end of war. In 2009, the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia sentenced him to 29 years in prison for war crimes, including a campaign of sniping and shelling citizens of Sarajevo.

One of the sniper nests was at ”Špicasta stijena,” the hill just above our street, where my brother was shot from. The name of the murderer we still do not know.

I keep this chocolate wrap, seemingly a small thing, just a piece of paper, yet for me and my family a distant memory of a happier life. Piece of my life, a moment of us together, laughing and enjoying our worryless time. It gives me my brother back, reminds me of him, makes it feel as if he’s alive again.

In 2019, I initiated the project “Sniper Alley Photo” as a personal quest for a photo somebody may have taken of my brother during the siege, as well as other kids who lived in Sarajevo back then. At the same time, we wanted to convey the experiences of war photographers and preserve the forgotten stories of wartime horrors about the longest siege of a capital city in modern history. The initial idea grew into an online museum with memories of all of us who survived the Siege of Sarajevo. Today we have 130 galleries and our database has 370 names on it. We are not even halfway through.

Back in 2019, I had no idea it would be as complex and wide as it is. Some of the photos we have now were never seen before. We came across lost or forgotten film negatives and photos that were never planned to be shared. Some are like special treasures because one never knows who will be recognized in them and what they will represent to somebody else. In the coming years, there will be a lot of boys and girls, now men and women, who will get their photos they have never seen before. What I was trying to do for myself I’ve achieved to do for hundreds of others.

With a stroke of luck in 2021 I did find my brother’s photo, taken by American photojournalist Thomas James Hurst in 1993 just a few meters away from the location of my brother’s murder. It’s difficult to describe my emotions when I see it. Tears were flooding because of a single photo, but not any photo. That year, that day, that moment, I will never forget. Thanks to this photo I have my brother with me, again. By then we only had photographs of his funeral and everybody was present except him who was lying dead in front of us, wrapped in shrouds. Those images were sad to look at, they didn’t have that relevance but of historical value. They were treated more as a document rather than something that’s beautiful and wanting to be seen.

What could be nice from war, you could ask, but believe me, a single audio file, voice, video or just an image can give you more than you imagine. Those who don’t have those elements know it best. I was one of them but not any more.

My family was fortunate since during the war we were not expelled from our home and our possessions, which we had before the war, were not destroyed when it ended. We were never refugees which gave us a small dose of strength years after the siege. Rebuilding lives was much easier for my family than for many others.

But, our lives were shattered, marked forever by that sniper shot.

Having been through the war and loss, today, as genocide in Gaza is taking place, I can’t but think of the children there, people I consider my brothers and sisters, who lost everything they had. Once I was in their situation. Some of them did not lose only their homes and photos, but everybody in those photos. I’m sure there are people who don’t have any memory of their killed ones and no memory at all when it comes to their past lives. School diplomas, wedding certificates, many memories preserved just on paper, love letters, invitations, bills you keep for whatever reason—all of it gone forever. Burned, destroyed, and vanished from their ruined lives.

Only memories left.

If even that.

I can imagine how many kids from Gaza will be searching for their loved ones in the years to come. How many will be desperate to find just a glimpse of something, anything to satisfy the urge to hear the voices of their loved ones. We are finding that in a tape recording from 1994 where we can hear Amel’s voice while he plays with friends. That audio is priceless simply because we humans forget the voice. Time passes and it does disappear from our minds.

Twenty four years after Amel was forcibly taken from me, I went on a journey in the search for something. It was a task only I could have done. Nobody and nothing can replace him and that’s why I have to allow his memory to live in me and that’s why I keep reliving in that memory. Everything I have done, all I have achieved, was and is for the love of my brother. He and his name never fade away, he sparks my motivation and keeps me going through many post-war battles.

My battles, the battles of my family, are now for all those who were murdered, burned to death, raped, slaughtered in wars. When people are gone, those who stay behind can represent them, and can confront their enemies with the truth. Survivors of war can’t afford to stay quiet when we see wars and crimes are committed to someone else. That luxury of silence we don’t have. How could we sit idle and watch the same suffering we endured taking place somewhere else?

My life might be defined by that day when my brother was killed. My soul might be wounded forever. But as a person, I am not damaged or deprived of love and empathy. So I keep preserving the truth and the facts, for my brother, for all of us.

One photo at the time. One by one. Till I breathe.

Džemil Hodžić

With more than 20 years of experience in TV and media, Džemil is a video editor working on documentaries. As part of his dedication and unique mission to preserve Sarajevo’s war history and his goal to pay tribute to photographers covering the Sarajevo Siege, he’s the author of The Story Behind the Photo video series, documenting witness accounts from world- renowned photojournalists.