Cover photo: Baxtiyar Ali portrait.

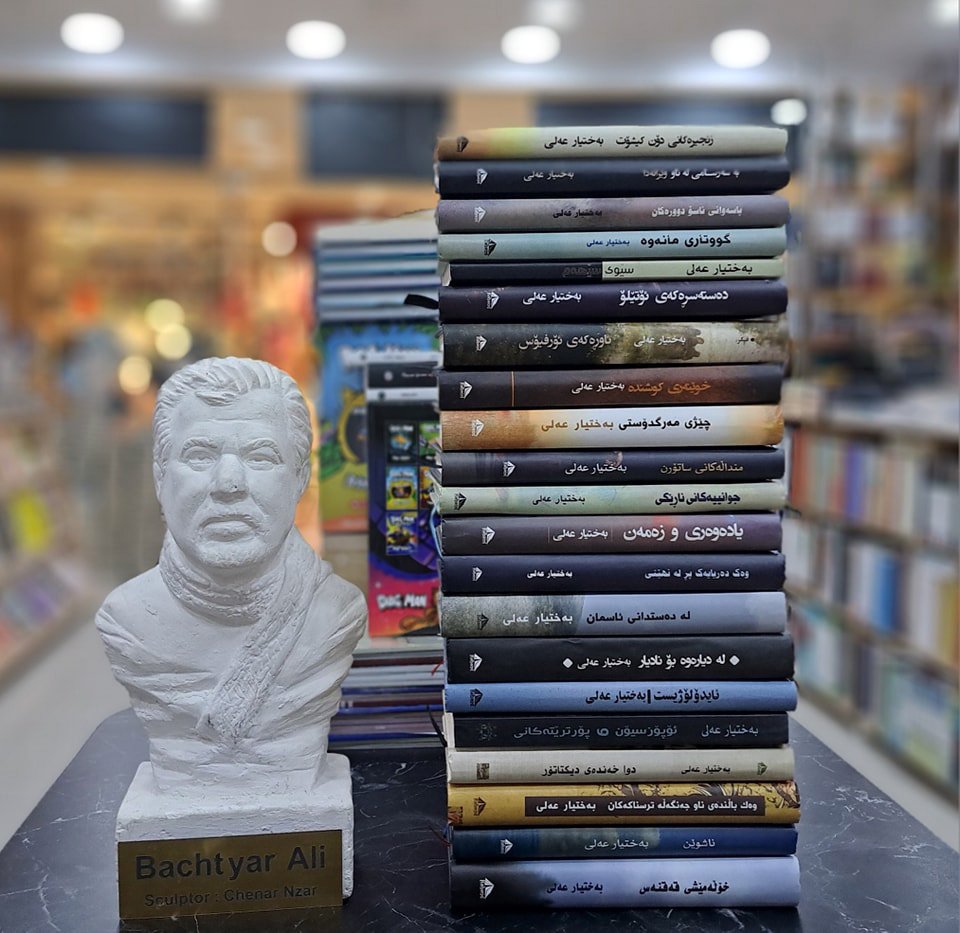

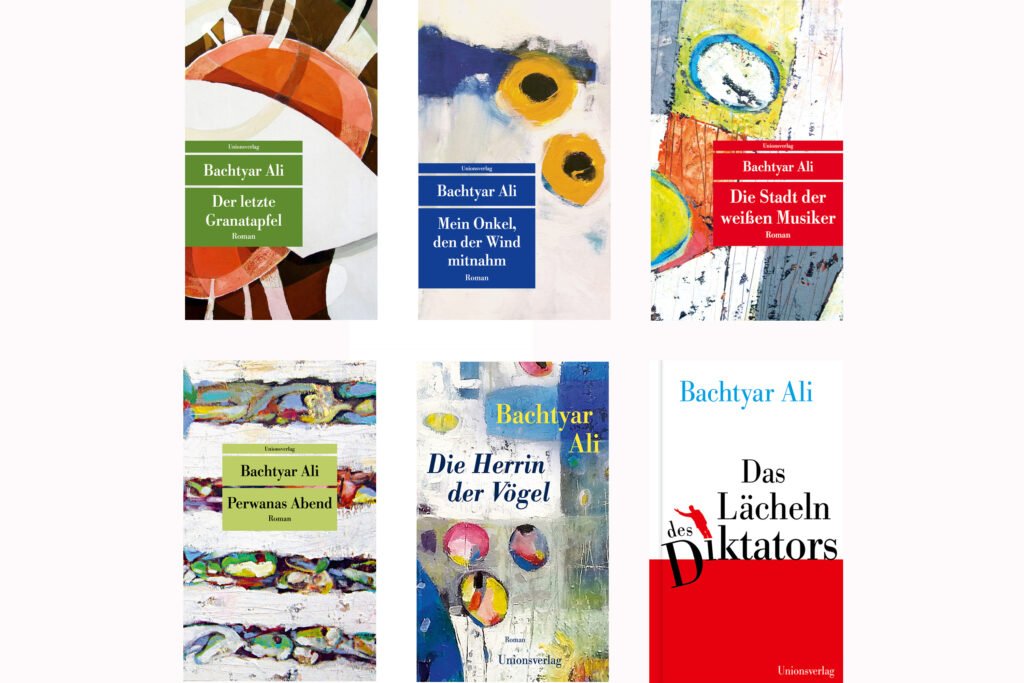

Baxtiyar Ali is the most prominent contemporary writer and poet from the autonomous Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Born in 1966 in Sulaimaniya, he survived Saddam Hussein’s regime. Injured during student protests, Ali left his studies in geology to devote himself to poetry. His first collection, Gunah w Karnaval (Sin and Carnival), appeared in 1992. After the 1991 uprising and the partial autonomy that followed, he expanded his literary work and contributed to the philosophical journal Azadi. His novels, poems, and essays earned him broad respect in Kurdistan for his independent stance and his open criticism of political and societal conditions.

Since the mid-1990s, he has lived in Germany where he has received the Nelly Sachs Prize in 2017 and the Hilde Domin Prize in 2023.

Writing far from home, stripped away from noise, pressure, and expectation, Ali told us, gives him the freedom to protect Kurdish culture as a language of thought rather than just a means of survival.

In our conversation, Ali spoke about exile as a place where a writer can finally sort ideas, look at his own society without fear, and turn the Kurdish language into a medium for reflection. What emerges is a portrait of someone who treats exile not as loss, but as a working condition that allowed his ideas to take shape.

TP: What does “homeland” mean to you today—a place, a language, a memory, an audience?

Baxtiyar Ali: When we speak about homeland, we run into an old, maybe unsolvable problem. We draw a radical line between the world and the homeland, as if they were on opposite sides—enemies. This fracture is deadly because it separates what can never truly be separated. It is as if a quiet war is being fought between these two ideas.

We, writers, carry a responsibility, not only toward language, but also toward humanity.

But what does that word even mean: humanity? It sounds enormous, distant, faceless. If humanity had a face, for me, it would be the face of the tormented people of my homeland. In their suffering, but also in their hope, I see the truth about all of us. My homeland shows me the real state of humanity. It is my thread to it, my place of understanding, the source of my compassion. Homeland is not a point on a map. It is the beginning of all questions, the quiet voice that stays even when you leave. You can walk away from your homeland, but the questions it asks will always travel with you.

Many writers in exile speak of a kind of “linguistic uprooting.” Have you felt that? Do you write differently in English or German than in Kurdish?

At first, I wanted to write in Arabic. But with the very first sentence, I felt a strange, almost suffocating sensation, as if I were watching myself from far away. Most writers work in their mother tongue, so why shouldn’t I do the same?

I‘m committed to Kurdish with full conviction. This language, our language, has always been at risk, in the past, in the present, and likely in the future as well. Politics is only one part of that threat. A language can die in many ways. It can grow quieter, lose depth, retreat into the narrow space of everyday life; if it is not also a language of thinking and writing.

Among Kurds, storytelling lived for a long time on the margins of our cultural life. Many of our tragedies were lost that way: unsaid, unwritten, forgotten. Yet, a people without literature is a people without memory. Language is not just a tool, not merely a game of sounds and signs. It is a river that connects generations, tying the present to the future.

Only through language can a people protect its continuity, its durability, and its inner light. Language is a creative force. It shapes us, not only as individuals but as a community. Indeed, many intellectual fields were new terrain for Kurds. We had to read and study other languages to discover ways of thinking methodically. But the task of our generation was, and remains, immense: to turn a language of poetry into a language capable of thought and storytelling. To accomplish that, we need to stay deeply rooted in our language, close to it, familiar with it, faithful to it. Because within it, and only within it, lives the memory of our people and the possibility of its future.

Has your writing changed formally or thematically since you no longer live in Kurdistan?

I wrote almost everything I have written, maybe ninety-five percent, in Germany. [The years in Kurdistan and in Germany] form two large and very different phases of my life. Here I could finally think in quiet, write with focus, and organize my thoughts. Life in Kurdistan felt like a swirling vortex. Political events, social tensions, and never-ending cultural conflicts steal a writer’s time and inner strength.

My lifestyle changed drastically. Living at some distance from readers and other writers sometimes feels like paradise—free from noise, opinions, and expectations. Because in writing, there is something worse than censorship: the thoughtless comments of writers and readers who have no idea about literature.

In Kurdistan, I was an emotional, often furious poet. Many philosophical and cultural questions haunted me, especially the question of cultural poverty. Why are there so few books in Kurdish? Why have the peoples of the Orient not produced great philosophers? I wanted to understand the mindset and the barriers that created this historical vacuum in cultural life.

Here in Germany, my view shifted. I focus more on the ideological structures that shape the Orient. Poetry stepped aside and novels took its place. It was a radical turn, a conscious break, a new beginning.

Would you say exile sharpened your view of power, identity, and belonging, or did it splinter it?

When I came to Germany at thirty-three, I had spent my entire life under dictatorships. The political form of these regimes was the harshest part, of course, yet violence shows itself in many subtle ways, too. Many quiet structures crush people gently and invisibly. Religious worldviews and rigid moral codes degrade and oppress people, just as political repression does. In such a society, it is nearly impossible to live with a free sense of identity. Belonging is saturated with coercion.

I constantly searched for another kind of belonging and identity, one shaped through resistance to parties and societal pressures. The inner fracture created by life in my homeland stayed with me for years. Only here did I find a space where I could overcome it.

People often say exile is a place of suffering. What does this opinion overlook?

You cannot separate human history from the history of migration. Movement, escape, and the search for a new place all of that belongs to human nature. Yet, racists in Europe convinced us that today’s migration is something unusual or threatening, and they managed to plant a sense of guilt in us. Feeling like strangers and treating exile as punishment is deeply tied to the culture of racism. This way of thinking was ingrained in our societies over the centuries.

Between 1820 and 1914, before the First World War, almost six million Germans immigrated to America. Today, about one-sixth of the US population has German roots. This shows that migration has never been an exception, but a constant part of human existence. People have always left, in all eras, out of need, hope, fear, or longing.

Exile is painful. Being an exile is not pleasant, but sometimes it is necessary to save the lives of millions.

We often overlook how essential migration and exile were, and still are, for the survival of cultures and civilizations. Imagine the twentieth century without the possibility of exile. What would have survived of German culture and science if Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Lion Feuchtwanger, Anna Seghers, Alfred Döblin, Albert Einstein, Hannah Arendt, Sigmund Freud, or Theodor W. Adorno had not been able to flee?

Exile not only saves lives. It saves thinking, art, language, and the memory of humanity.

What intellectual or creative freedom has exile given you?

As a Kurd, it was never easy to remain unpolitical. Early on, I learned that we rarely see the world as it truly is. Most of the time, we look through the lens of politics. Politics and religion shaped our lives, often more than we wished. They demand that you join a party or an ideology, that you belong somewhere. But this pressure can cloud your vision of reality and create a false image of the world.

It is still dangerous to refuse political convictions. Freeing myself from that pressure was long, difficult, and almost impossible. But with time, I realized how important it is to shed political and ideological prejudices. Only then could I see the world again as a whole: calm, connected, without enemies and borders.

But I have to be honest. This change did not only happen in my thinking. My relationship to my feelings and my inner world also shifted profoundly.

Is there something you could never regain?

Yes, many things. You lose almost an entire world, the world in which you grew up. These small, lost things always made me sad. The shadow of my mother in the house, the scent of flowers in the garden, the sound of the wind. The taste of summer fruit, the murmur of nature in Kurdistan, the colors of the spring grass.

I had to learn to live far from all of that. I have experienced many beautiful things here, too, of course, but what I lost cannot be replaced.

When you see young Kurdish writers working outside Kurdistan today, do you see yourself in them, or do you see something new?

We belong to two different generations, and our experiences could not be more different. I spent many years of my life in the war. For us, survival was the priority, which is perhaps why the value of life plays such a central role in all my books. I wrote for more than fifteen years with no hope of publication. We had no access to books. We wrote in a world where books were seen as foreign and dangerous, where a thoughtful reader was a rarity. I often found myself in difficult situations. I had to stand up to Islamists, nationalists, and radical Marxists just to maintain my identity as a free writer.

Young Kurdish writers working outside Kurdistan today face very different questions. Identity and the connection to Kurdish roots are at the center. Family conflict matters greatly to them, as does the struggle for recognition as a second-generation.

To be honest, there are only a few points of overlap between us.

And finally, do you believe one can ever truly “arrive,” or is exile a kind of permanent intellectual motion?

Arriving is almost impossible, and that may be a good thing. We remain strangers, outsiders, or a rejected elite. In the homeland we come from, we are often seen as inconvenient guests who no longer think and feel like the people there. And here in exile, we are seen as a disturbance to the country’s cultural and national identity.

But we must use this in-between position to create new values and new ways of seeing, both here and there. Our condition as “eternal strangers” gives us the strength to criticize the fascist longing for homogeneity and to open new perspectives within dogmatic systems.

To be a stranger is tragic, yet also necessary to imagine a world in which no culture sees itself as dominant or superior.

This interview was conducted in German and has been translated into English for this publication.

Sham Jaff

Sham Jaff is a freelance journalist in Berlin. She writes the weekly newsletter whathappenedlastweek.com about the so-called Global South. Currently, Jaff works as an editor for The Amargi.