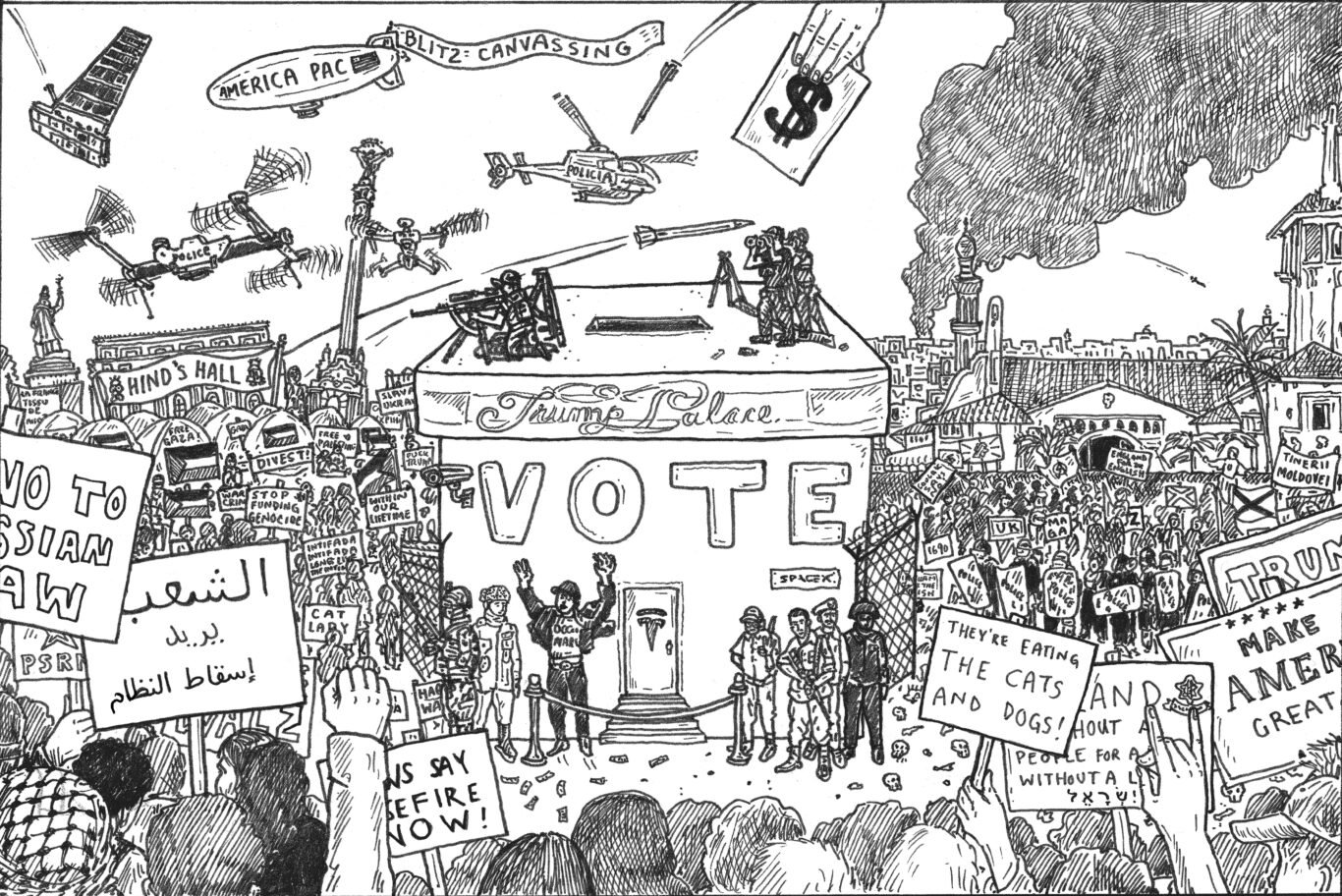

Cover illustration: ©Chris Russell

A Year of Elections, a Year of Reflections

by Editorial Board

December 4, 2024

On the eve of 2024, the media was flooded with articles proclaiming that this year would be “the year of elections”. In our first editorial, we also noted that more than 70 countries worldwide would be involved in elections—ranging from municipal to presidential.

This year more than 2 billion people across the globe headed to the polls, marking an unprecedented engagement in electoral processes: some votes tested the limits of state democracy, while others served as purely cosmetic operations for dictatorships. All of the votes come amidst a backdrop of growing economic and geopolitical strife; with the ongoing genocide in Gaza, unfolding alongside a ceasefire in Lebanon; the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine far from an end; growing tensions between the largest economies of the world; and ecological crisis.

At Turning Point we believe that electoral politics, while important, are only one part of the picture. Around the world, power is increasingly exercised outside the confines of formal political institutions. On one side we see the rooting of power in informal networks and grassroots movements, yet on the other we find it exercised by economic elites, warlords, and transnational institutions. A variety of actors outside the traditional political parties are shaping the political landscape in ways that elections alone cannot fully capture. Moreover, voter disengagement is a growing reality in many of the world’s most established democracies. The apathy toward voting, particularly in Western countries, signals a deepening crisis of confidence in the existing political system. The legitimacy of elections is being called into question as more people feel disconnected from the political process, viewing elections as little more than a symbolic gesture. The results of these elections—when they occur—rarely reflect a broad and unified will of the people. With low turnout and participation, they often only further the fragmentation of society.

In this issue, we try to look at what has happened in different countries and situations. We aim to offer a nuanced understanding of the impact that the “year of elections” had on the global landscape. Although we know that people do not pay the same price for the costs that capitalist modernity imposes on people of the world, some issues are common: the rising prices for food, fuels, and other essential resources have lowered the quality of life of billions of people. Meanwhile peoples across the world face increased fear as geopolitical tensions are exacerbated. Polls showed that costs of living played a pivotal role in India, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), lost the absolute majority for the first time. This was also the case for the South African general elections, which ended with the historical loss of ANC in May. Another critical factor driving political dynamics is “defense and security” which has taken priority in many places, especially in the so-called “hot spots.” From Finland where the new president Alexander Stubb campaigned for full participation of non-aligned countries in NATO, to Taiwan where conflict with China was the key protagonist in the presidential and parliamentary elections.

In November the eyes of the world were all on North America, painfully observing the campaign and reelection of Donald Trump as president of the United States. In the lead-up to Trump’s 2024 election, there was an intense push for voter data to target demographics critical to the election. Eccentric billionaire Elon Musk funded a widespread data collection effort that employed subcontractors who were accused of deceiving workers—stranding them far from home with promises of canvassing work that never materialized. We gained inside access to Musk’s ground operation, unveiling a chaotic work environment replete with fraud and worker exploitation. While subcontractors have been employed, Turning Point can reveal financial links between these subcontractors and Musk’s company.

In Turkey, the vote is merely a way for the regime to prove its ability to keep the population in order. This reality was made starkly clear during the last municipal election after Erdogan’s party faced its biggest defeat in decades. In several Kurdish provinces the government prevented elected officials from taking office and often imprisoned opposition representatives. Gözde Çağrı Özköse, a Turkish journalist, will analyze the changes of this post-election political landscape.

Keeping an eye on Europe, we will begin with a focus on the elections in Austria, a case that can help us better understand the rise of the far right and the shifting dynamics of political power in the countries of the old continent. We will also profile a huge part of the European population that refrained from directly engaging in the elections. Notably, the European parliamentary elections showed that the majority of the population actually didn’t vote at all. We want to understand why and who are the non-voters, the biggest party of Europe. Pietro Vicari, researcher from Bicocca University in Milan, will profile them.

We will not only examine official processes but the underlying conditions that make these elections possible—or, in many cases, impossible. As the world grapples with growing authoritarianism, shrinking communal space, the rise of far-right movements, and more wars, the question remains: What does it mean to build a democratic society in the 21st century? As we reflect on this in the “year of elections,” we urge our readers to consider that liberal and state democracy, in its traditional form, seems to longer be a sufficient framework to understand the complexities of global politics.

While each of these cases offers a distinct snapshot of electoral democracy in action (or inaction), they all share a common thread: they are taking place in a world where democracies—both established and emerging—are being tested as they face unprecedented challenges. From economic decline to climate crisis, as we look ahead, the need to renew democratic processes, to overcome these challenges, is clear. The future of society will not be determined solely by the outcome of ballots but by our collective commitments. While we focus on what happened in this election year, we must never forget that the struggle for democratic modernity extends far beyond the ballot box.