Cover photo: Sanhan and Bani Bahul district in Yemen’s Sana’a province, February 2013. Two young members of the local al-Mojalli tribe stand in Beit al-Ahmar. village, home Yemen’s ex president Ali Abdullah Saleh’s tribe. The men are choosing the highest mountain to set up an improvised poligon to learn the perfect usage of kalashnikovs and other individual weapons. © Laura Silvia Battaglia

During the 2011 Yemeni Revolution and over the months before the 2014 civil that concluded in the Ansarullah “Partisans of God” militia’s violent seizure of power in the capital; Houthi supporters could be found amongst a broad movement of Yemeni citizenry who united in the hopes of founding a new state. Instantly recognizable in this movement by their tables featuring dozens of CDs with speeches by Hassan Nasrallah, leader of Lebanon’s Hezbollah, in the Sana’a University area. Of the many CDs, one was always selected for public broadcast on an audio loop—you knew immediately, just by the sound, from a distance, where to look for them in the mass of tents of the permanent sit-in. They guarded the area assigned to them day and night during the protests, they were particularly kind to foreign reporters: the oldest always offered tea, the chatter was guaranteed, and all the conversations took a certain turn, steeped in acrimony, when the recently deposed Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh was mentioned. There was not one, among the Houthis, however young, dressed in a Western style. The scial, typical Yemeni turban, was always worn on every head; the jambia, the ornamental dagger, was wrapped around every belt. In the afternoon, bundles of qat—the typical Yemeni chewing drug— would appear for collective relaxation; the Kalashnikovs always hung from nails or found their place on the ground. Of the broad citizenry that had taken part in these movement for a different state, the Houthis were for us reporters the most typical, characteristic and fascinating community of North Yemen and their pride in their identity was convincing, to the point that the local representatives of the European Union, the United States and other international chancelleries gave them a seat in the National Unity Conference that was supposed to lead Yemen towards new laws and a new government—only to be sabotaged, among other tribal groups, by the Houthis themselves.

For anyone who had the opportunity to observe them as they descended in droves from the city of Sa’ada in the far north of Yemen, right on the border with Saudi Arabia, for the occupation of Sana’a in October 2014; their authoritarian determination to seize a country during a difficult period of political and economic transition, would have been immediately clear. Strong in will and driven by a passion for revenge, equipped with a powerful artillery financed by Iran; alongside the support of critical institutions of the state apparatus (politicians, military, and the police)—they succeeded. Success came at a price: the militia signed a pact with the devil, the former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who returned from Saudi exile blinded by power, so much so that the militia would kill him two years after having used him to gain access to the secrets of the state.

Clearly the Houthis were not carrying out the second Yemeni revolution but a counter-revolution that would throw the country back two centuries. The only thing they offered Yemeni society was safety: thereafter impervious to al-Qaeda infiltration, suicide bombers, attacks on institutions, hospitals, mosques and schools, which had never been lacking in previous years.

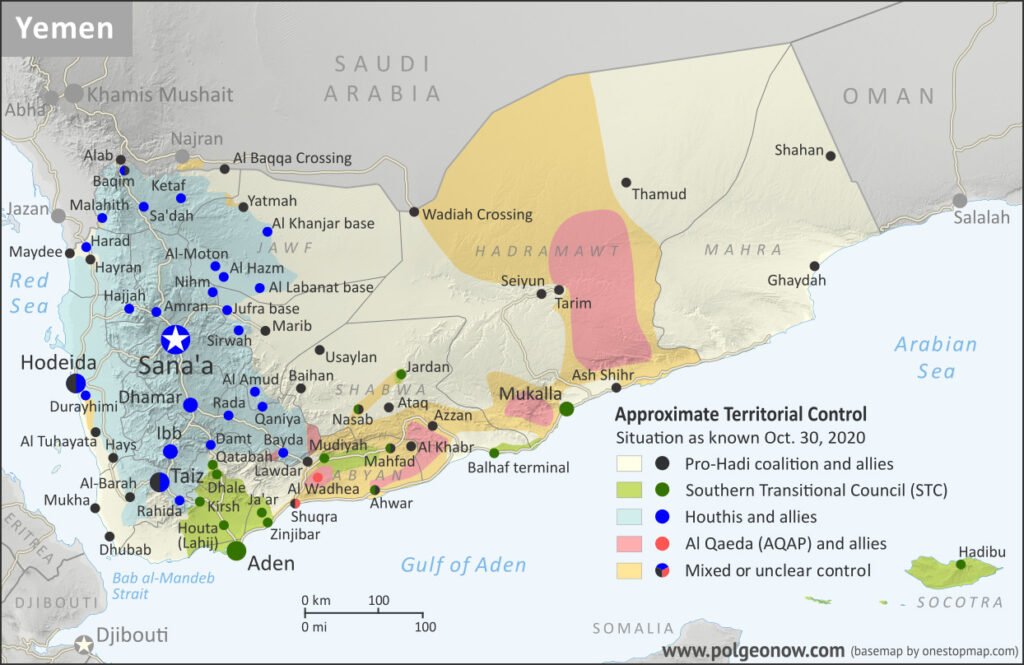

For a decade, despite having established a solid de facto government, and the loyalist government and its regional allies—Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in particular —had a hard time with ground battles between the Jizan Valley on the northern Saudi border and the Marib governorate. With targeted assassinations of Yemeni government’s generals and politicias carried out with Shahid drones in southern Yemen, from Lahji to Aden, the Houthis have appeared as the embodiment of the stereotypical Arab militiaman: slippers and Kalashnikovs, rebellious curls under the turban, a finger pointed to the sky to ask Allah to bear witness to Saudi crimes, a certain excitement caused by drug use, and last but not least, the very young age of most of the fighters on the front line. Demonized by loyalists and the Saudis, Ansarullah representatives have nevertheless managed to play the popular force card very well: embodying the original and real Yemen, a Yemen threatened by petrodollar monarchies and spineless national governments, viciously attacked by European and American-made bombs launched by the Saudis, which starve and kill Yemeni children. And its all true, for those who have lived and seen the country in every phase of the now almost ten-year war, none of these claims can be disputed. Only one piece of the story is missing: the militia of Northern Yemen, to achieve its goals, has established a system of governance based on totalizing control of citizens. As the human rights organization Mwatana has documented, under their reign draconian laws and social conventions are strictly imposed: the submission of women, forced conscription of young people into the war; the economic blackmailing of traders through threats of retaliation; the arrest and torture of any critical, non-aligned or even suspect subject. A perfect reproduction of the Iranian parent company model, with a particular declination imbued with Yemeni nativist pride and a Shiite-Zaydite philosophy that leaves its followers waiting for a messiah to lead the people. Clearly, the Houthi governance and the security apparatus is modeled on the Iranian Revolutionary Guards—better known as Pasdaran—who have themselves always stood as a reference for the Lebanese Hezbollah.

The consequences of their rule has come out very rarely in international reporting. The Houthis have been very careful in strictly controlling the (few) journalists who have had access to their territory—except for rare cases of dual-nationals reporting undercover—the world is vastly unable to understand what North Yemen has become. In the Arabic-language press, this unpleasant reality has instead been used by the pro-Saudi media as a club, fully justifying their targeting of the country through coalition of regional forces that together incessantly rain bombs that—according to the United Nations—have killed up to 377,000 people in 2021 alone.

Influencers: from the “messiah” Abdulmalik al-Houthi to Rashid, the “pirate” of the Red Sea

To understand the media capacity of the Houthis, voiced through internal and external narratives, it is enough to observe the phenomenon of the two most well-known influencers of the group. The first is so by statute, investiture, tribal role, conviction, ideology. Abdul Malik al Houthi, son of Badreddin and brother of Yahia and Abdul-Karim, he is the deus ex machina of the Ansarullah party. An almost mythological entity and political-spiritual figure, he appears and can be heard at all hours on the party’s national channels, on television and on the radio, but no one knows exactly where he is and where he speaks from. His messages to the nation are steeped in messianism, Yemeni pride, contempt for the Gulf monarchies and for the loyalist republic, but above all they are aimed at restoring the idea of Yemen’s return to a form of original Islamic autarchy, under the aegis of Zaydi Shiite Islam, which is now dangerously close to the more well-known Twelver Islam.

Such an imperative is orchestrated with not only great moral vigor but also courage before a corrupt world dominated by the Zionist enemy and the American super-power. It is a sort of “make Yemen great again”, projected towards a future in which universal judgement is anticipated and the advent of a restorative messiah. Awaiting redemption, it is seen as an utmost necessity to equip ourselves and avoid making behavioral errors that could cost us dearly in the afterlife and destine us to hell. The moral pillars of this project are organized principally around faith. A faith which in diametrically opposing itself to Sunnism, has rendered the possibility of a peaceful and plural Yemen impossible. And then there is loyalty to the monarchic-religious model of a country no longer republican, but structured around the Imamate. Education only for males, religiously based and espousing strength, the party, family, and sacrifice until death. Female education on the other hand stigmatizes the public role of women, increasingly encourages their renunciation of education in schools, preaches religious preparation and a cloistered married life as a necessary premise for loyalty to the party and its values. This project has very little to do with the country that Yemen was before 2014, and certainly has nothing to do with what it was in the Seventies and Eighties: the inoculation of al-Qaeda propaganda in the Nineties had already caused abundant disasters, at a time when young Yemenis were recruited to reach Afghanistan and work for Osama bin Laden. The rise of the Ansarullah party of the Yemeni Houthis is the other side of the coin in the rise of al-Qeda: opposing ideologies executed through the same tools; attracting different generations of an impoverished and disappointed youth.

And than there is Abdulmalik al-Houthi, whose ineffable presence and incisive and stentorian preaching tone, hypnotizes and fascinates the Yemenis of the North. And for those who retain doubts about the preachings, there is no alternative political base to turn to, one is stuck forever in a country from which no exit is in site: the passports recently issued by North Yemen, since the Houthi government is not internationally recognized, are not valid for expatriation. Further, they are not valid for any Yemeni, except Houthi officials, who travel to the few countries friendly to the party: Iran, Russia, China, Lebanon.

The choice to enter the Israel-Gaza conflict with kamikaze naval and air actions has since made Abdulmalik known outside Yemen, at least in the Arab world. His foreign policy positions on the conflict have in turn begun to provide him a broader following—capturing the minds of even those who wouldn’t have given him a cent ten years ago. This new public has come to believe in the good intentions of the militia: ‘the only force’—together with Hezbollah—‘capable of giving Israel a hard time.’

Despite this rise in interest, Abdulmalik is not foremost concerned with the non-Yemeni and non-Arab audience as he is very faithful to the traditional image of the Yemeni man from the North, in shawl and dagger. His assertive and dictatorial voice does not make him very different, from the leader of the Lebanese Hezbollah, recently killed by Israel, Hassan Nasrallah. Despite this, it can be noted that a nineteen-year-old from the city of Ibb, named Rashid, has achieved this international following after becoming a TikTok and Instagram star last November, 2023. Rashid posted a video of himself edited into footage taken by the Yemeni Houthis as they pirated the Galaxy Leader—a ship flying the flag of the Bahamas—taking the entire crew hostage in a Mission Impossible-style operation—filmed with Go-Pro cameras and shared on the social media of their official channel Al-Masirah. Rashid, in an interview with the well-known Twitch streamer Hasan Piker, explained to the influencer’s 2.6 million followers that he likes to be called “the pirate of the Red Sea” and that he is simply “a Yemeni who supports the Palestinian cause.” Rashid also went on to say that he loves “big adventures” but that he does not want to discuss the fact that he has become a sex idol among British girls, who compare him to the actor Timothee Chalamet. The young man, whose accounts on TikTok, Instagram, X and Threads have been removed for inciting terrorism, subsequently changed his nickname to “Timhouthi Chalamet”. The 19-year-old has earned the cause of Ansarullah a lot of sympathy, especially when he declared he was “honored to be bombed by the United States, as now we are confronting them directly.” In the West, Rashid has reconciled pro-Palestinians around a moderate anti-American sentiment. His face and his phisique du role have done the rest.

Role of the Houthis in the Israeli-Palestinian War: What Contribution Will They Make in the Next Phases?

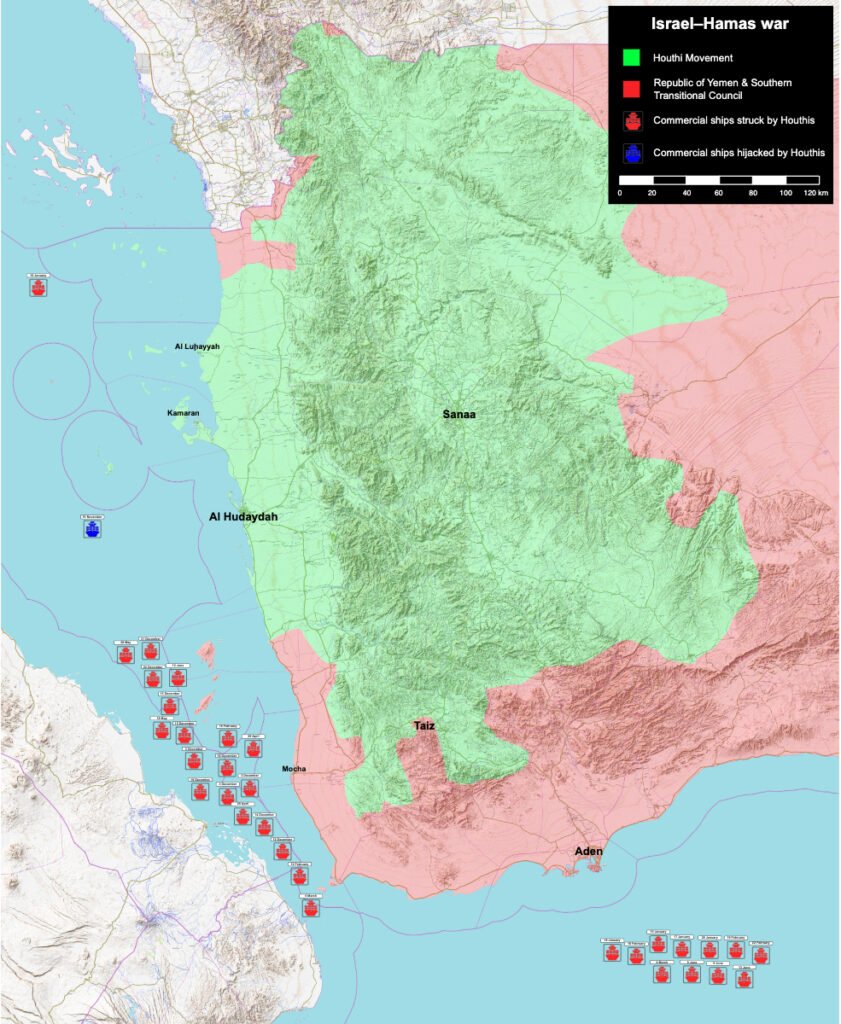

Nine months after their declarations against Israel a low-intensity war has unfolded. This has in turn resulted in direct interventions by the United States and Great Britain who have carried out operation “Prosperity Shield” and “Poseidon Archer”. Despite the advanced arsenals of the two countries, the success of these operations has been limited. A few weeks ago, Vice Admiral George Wikoff, commander of the US Naval Forces Central Command, declared that the Yemeni threat (Yemeni Armed Forces), both to navigations in the Indo-Mediterranean and to Israel, repeatedly hit by drones, cannot be defeated. The general was quite clear, speaking during an event hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies: “We need the involvement of the international community and we need to explore ‘alternative’ methods,” The Business Insider reports. The reality is that, for more than eight months, the coalition has tried to secure ships passing between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden but the North Yemenis have relentlessly hammered all targets, with missiles and drones, without giving in. It is not pleasant for the US forces to have to admit such discomfort towards an underestimated militia, measured by the value of the slippers it wears. And so they have moved on to more ferocious methods: an air raid on the Yemeni island of Kamaran, about 70 kilometers North-West of Hodeida. The island was occupied a few years ago by the Houthis and, according to both their statements and intelligence reports, has become a strategic outpost equipped with launch pads, drone and ammunition depots, runways for armed helicopters and a dock for the speed-ships they carry out raids with.

The aces of will and tenacity up the sleeves of Ansarullah and the Yemen Armed Forces, is not the only factor behind their resilience. There is also the holy hand, or rather two, that contribute to this success. It seems useless to dwell on Iran now, but we will do it anyway: the Islamic Republic has gone from circulating suitcases full of toman (the Iranian currency) in Yemen for which it filled the pages of local newspapers in 2013, to giving logistical, military and operational support to the Houthis, especially since the militants have enriched their artillery, designing and building an evolution of the Iranian Shahid-type drones. The new Yemeni drones (the Sammad 1, 2, 3 and Qasef 1 and 2K models) are not a novelty fed to Sana’a by the Iranians, the Yemenis have never been the only executors in the strategy of their parent company in Tehran, but have always put their own manufacturing savvy on the table. A local engineering ingenuity that has accomplished assemblies from the most unlikely pieces of the most diverse devices. Whether for ground or air, depending on the needs of the moment. But as the going has gotten tougher, another holy hand has come into the picture: help from Moscow. So it now seems established, according to intelligence leaks published on the Middle East Eye website, that Russian military intelligence, the GRU, has set foot in Yemen to provide strategic know-how to the military wing of Ansarullah and that Sana’a has asked Moscow for missiles to advance their naval threat—missiles that Putin has not yet granted to the Houthis—thanks to mediation by Saudi Prince Mohammed bin Salman, as encouraged by the United States.

As Russia also enters the arena, it is easy to see that the stakes are very high. The world awaits Iran’s response for the murder of Hamas leader Ismail Hanyeh in Tehran by Israel. In this new landscape, the most widely accepted hypothesis is that Russia would like protection of not only ships flying the Russian flag, but also those carrying material of interest to the country. In this sense, Russian intelligence seems to have intervened as to ‘educate’ the Yemenis not to make mistakes. But there is more: in addition to the anti-American objective, Putin has never hidden the fact that he is interested in creating disturbances for Russia’s top oil competitor, Saudi Arabia. By staking interests in the post-war reconstruction phase in Yemen, a country with which Russia has had privileged relations in the military and education sectors since well before the presidency of Ali Abdullah Saleh; Russia on one hand hopes to weaken the shipping routes in the Indo-Mediterranean as to strengthen its bond with China and the promises for the realization of the Belt & Road Initiative; while on the other to move some “delicate” navigations to the Arctic route, the only one over which Russia would have control and centrality.

With or without the Russians, the Yemenis remain in key position to render their services to the Palestinian cause: with drones on Israeli targets, with missiles and drones on ships flying the Israeli flag, they remain the first militia to have directly reacted to the murder of Ismail Hanyeh, now openly confirmed by Mossad. One of their missiles hit a Liberian-flagged container ship, the Groton, which had left the port of Fujairah in the Emirates to go to Jeddah, in Saudi Arabia, via Aden. They are the real kamikazes of the Iranian axis.

The Houthi Pro-palestinian Fan Base That Ignores the Price Paid by Yemeni Citizens

The initiative and courage of the Houthis, who seek recognition in the Arab world as an entity that governs the North of Yemen and who in turn may participate in the next round of negotiations to end the war in Yemen, have made inroads in public opinion. In the West, the Houthis have a fan base that often coincides with the vast pro-Palestinian movement, both native Europeans or Americans and second generation. For those who know the history of Yemen in detail and the current condition to which the political representatives of the party closest to them—Hamas and the Yemeni Muslim Brotherhood (the Islah party)—are subjected, this affection towards the Houthis sounds frankly absurd, the result of one of frequent erasures of memory in the history of political ideologies.

I could not believe my eyes, in recent months, covering the anti-American and pro-Palestinian demonstrations in Jordan, when, from the back of the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood party (Jabhat al-Amal al-Islam) sit-in, after friday prayers, the Yemeni national flag was raised in the crowd, while the secretary general Murad al-Adaileh thundered the Jordanian group’s support for Hamas and the Yemeni Houthis against the Zionist enemy. I wondered if he knew the price paid by his party colleagues, the Muslim Brotherhood and Sunnis like him, over these ten years. Especially in the city of Taiz where the militia persecuted, arrested, tortured and sentenced them to death. This same militia that he himself was exalting in the square. I wondered if those who raised the flag knew that it is now the flag of the Yemeni loyalist government, not the symbol of the Ansarullah party of the Houthis that the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood admires and thanks. But this is politics, and one does not look too closely at the closest and most pressing cause, to be supported immediately, overturning history and rewriting its narratives.

With the new course of events and the international spotlight they have gained, the Yemeni Houthis have not become softer. When they declared their participation in the Gaza war alongside the Palestinians, one of the possible outcomes, knowing the behavior of the group, could have been reprisals for the personnel who work for international organizations in Yemen. Because, even if the militia depends on the UN for food and health assistance actions in the North of the country, it also manages the very large black market in the area with an iron fist. It can therefore also afford to carry out deterrent initiatives, to the direct detriment of civilians. Thus, last January, the group arrested what the Saba news agency defined as a “network of spies” who were alleged to have acted under the cover of international organizations to exchange information for the CIA—information that is now useful to the American and British coalition. The local media, controlled by the Houthis, have released interceptions that, according to the authorities, were proof of their guilt.

Among these men and women, there are eleven UN staff members of Yemeni nationality, including six members of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, particularly underestimated by the authorities but also by private citizens in Yemen after the failure of the special UN commission that should have investigated Saudi responsibilities in war crimes against Yemeni children. Much ado about nothing, because the evidence brought to the UN headquarters in New York was never enough to obtain the result that the Houthis hoped for, but that, all Yemenis believed was right based on the collection of data.

According to local human rights organizations Mayyun and Mawtana, 18 of these arrests took place simultaneously in different locations: the capital Sana’a, the port city of Hodeida, the northern cities of Amran and Saada. Among them, a manager of the UN supplier Prodigy has already been sentenced to death, not to mention that, to date, and starting from November 2021, fifty employees of local Yemeni NGOs, plus an employee of an embassy, have been arrested. A Yemeni diplomat of the central government who wanted to remain anonymous told me of the dramatic arrest of a woman in the middle of the night and of the tragedy that followed the protests of her husband who was also arrested on the basis of a new law, active for two years, that formalizes the “guard” of woman by the closest male relative. The arrested woman is now reportedly detained in the women’s prison of Sa’ada, in the far North of Yemen. The woman’s mother is appealing to all national and international authorities. At the moment, after a month in which only human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have come forward with public statements and detailed reports on the matter, even the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the Austrian Volker Turk, has denounced the assault and confiscation of real estate at the UN office, declaring that “it is a serious attack on the ability of the UN to carry out its mandate, including that relating to the promotion and protection of human rights.”

International organizations are finally showing understandable concern, after years of evidence gathered on arbitrary detention policies that not only eliminate the right to defense but are also sites where torture with red-hot irons, wooden sticks, assault rifles, constriction and attachment to ropes or chains on the wall, threat of rape and rape, in order to obtain information or false confessions, are all enacted. Nothing different or more sweetened than the torture practices currently practiced in the Israeli prison of Sde Teiman against Palestinian detainees.

In wars—it must be reiterated for those who have direct experience—it is the cleanest who are left with the itch. Maybe the only given measure to keep some kind of integrity is quantity: not asking what, but rather at what cost?

At this point, a year after October 7, with the risk that this war becomes fully regional, due to the direct involvement of Iran and after its enlargement in Lebanon against Hezbollah, the pro-Iranian militias in Iraq and Syria but especially Ansarullah in Yemen could become the ace in the hole of the pro-Iranian axis. From the Houthis, who have just launched a remote-controlled and unmanned naval drone raider against the Greek bulker “Tutor”, we can expect anything, being the kamikazes of the Shiite militias and having nothing to lose. At the moment, they have threatened to close to the navigation of the entire Strait of Tears (Bab el-Mandab) in front of the city of Aden. The Somali al Shabaab, despite being Qaedists, have already come forward to facilitate their work on the African side.

Laura Silvia Battaglia

Laura Silvia Battaglia is an Italian reporter, specializing in crisis and conflict areas since 2007. With a particular focus on Yemen and Iraq, she has covered ethnic, religious and gender minorities, migration, terrorism, and human and arms trafficking over the years. She is an author and host for Radio3 (Radio3Mondo) and a documentary filmmaker.