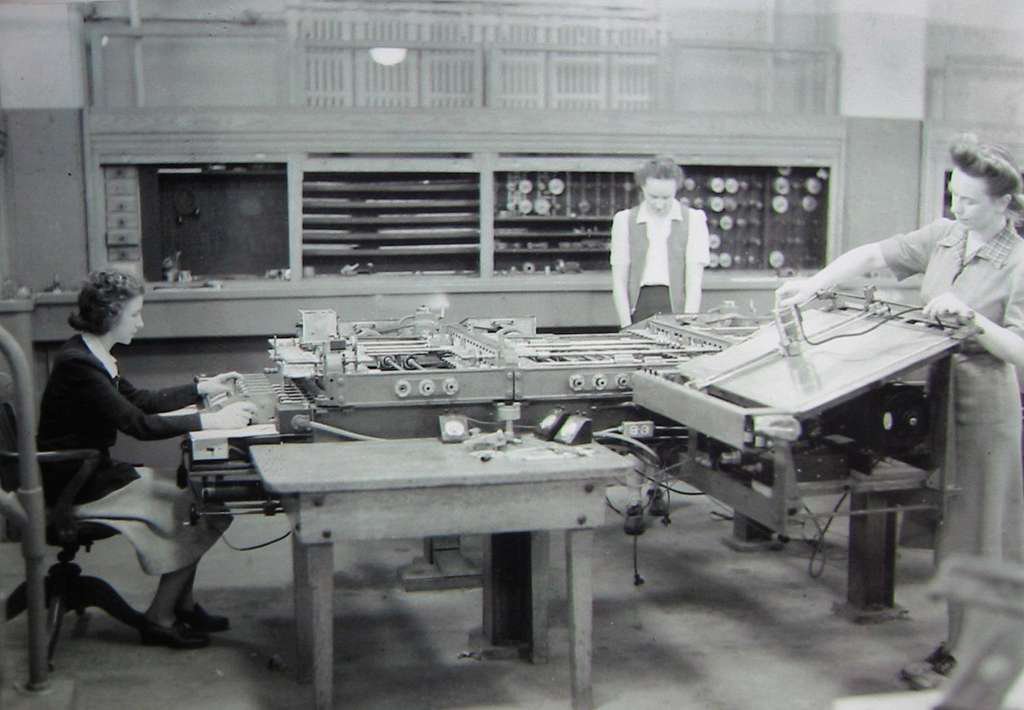

Cover photo: Programmers Ruth Lichterman (crouching) and Marlyn Wescoff (standing) wiring the right side of the ENIAC with a new program. Public domain.

For

Ada Lovelace, who wrote the first computer program in 1843 for Charles Babbage’s analytical engine

Grace Hopper, pioneer of computer programming

Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Meltzer, Fran Bilas, and Ruth Lichterman, ENIAC’s first six programmers

Frances E. Allen, the first woman to receive the Turing Award

Elizebeth Friedman who, with her team of code-breakers, solved numerous cipher systems (including enigma machines) used by the Nazis.

And all the women that have worked and work in technology.

I have been fascinated by mathematics and technology for as long as I can remember. When I was a child I used to play simple video games with the Linux penguin as the main character; looking wide-eyed at my father as he solved errors with the command line. Growing up, I began to realize that fewer and fewer girls liked mathematics and computers. For some reason, girls felt stupid and scared when approaching these fields, despite feeling confident in all other subjects. It took me some time to understand why this happened and continues to occur. I started to write this essay to channel the anger that this issue raised in me. It ended up motivating a reflection not only on the paths we, as a society used to get here, but on why and how we can shape the future differently.

Today, at least in the parts of the world where women have access to an education system, there are no laws prohibiting their access to technological and scientific fields. Nonetheless, they are highly discouraged to do so and—as data shows—discriminated against, paid less and given inferior positions in these workplaces. In the meantime, governments are narrating that they have reached gender equality. This is the face of the monster we have to confront today: liberalism. And even if it may seem at first glance less cruel, it is much harder to fight against, as it works on two levels at the same time: while enacting gendered oppression, it’s assuring everyone that patriarchy is an old thing.

In Artificial Intelligence (AI), most of the voices used are female ones: Alexa, Siri, and Cortana. And although the physical body is not present, the preference for female voices reinforces the idea of reliable, obedient and strong women; who are not truly empowered or in charge. This is how patriarchy wants women to be: submissive but “spicy” enough to tease men’s desire; intelligent but not smarter; independent but still in need of a man to take care of them; powerful, but not in charge. The imaginary of who a woman should be and what her role in society should look like is shaped through AI: secretaries, human agendas, personal assistants.

Historically, technical skills have accumulated primarily in men’s hands. Even when a woman is actually working in the tech field, it will be very rare for her to have a non-male boss or supervisor. This arrangement deepens the dependency on men and the sense of inferiority, which is something that women are already confronted with in everyday life. While doing research for this essay I came across the concept of “stereotype threat.” It is a psychological phenomenon that makes people feel at risk of confirming a negative stereotype about a group they identify with, and in doing so enforces their under-performance. This phenomenon is widespread among women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) studies and workplaces. This phenomenon only re-confirms the fact that womens’ lower participation in the field is neither a coincidence, nor caused by lack of interest or skills. And history shows us that things haven’t always been this way.

Programming Used to be Female

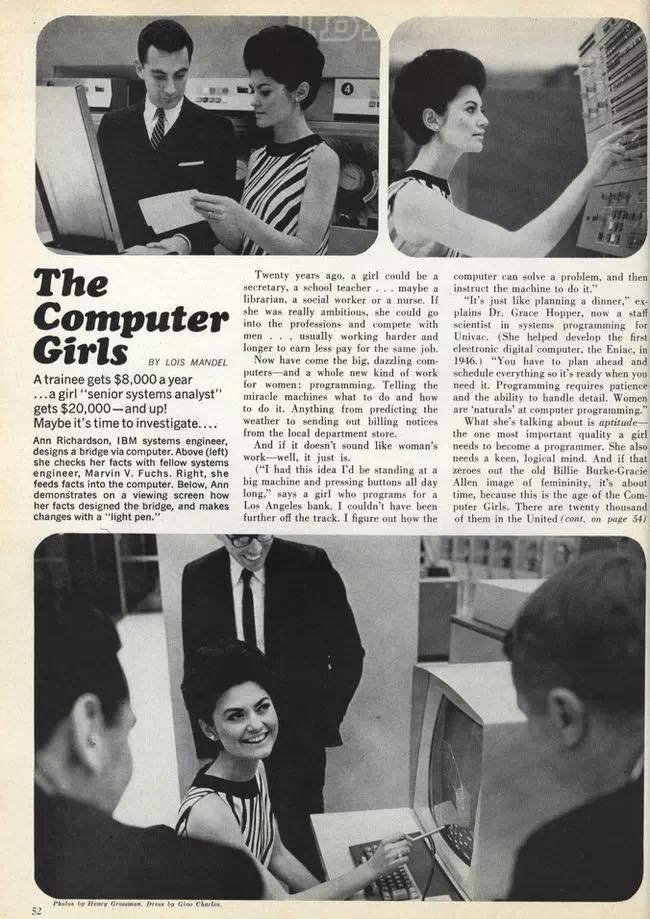

In 1967 Cosmopolitan published an article encouraging women to search for jobs in computer engineering. As a matter of fact, until the mid 1980s the majority of programmers were women. Men primarily enrolled in hardware engineering, which was considered more difficult than programming. The same article quotes the computer scientist Grace Hopper: “You have to plan ahead and schedule everything so it’s ready when you need it. Programming requires patience and the ability to handle detail. Women are ‘naturals’ at computer programming.”

In general, when a field starts to have an economic value, the tendency of the capitalist system is to try to obtain a monopoly over it. And this is one of the major reasons why women were excluded from computer science: at the end of the 1960s computer engineers started realizing the potential of their work. Computer engineers started creating study standards which, in fact, excluded women from the work they were already doing. Even more, they discouraged women from studying computer science. This shift in the academic field was mirrored in public perception. For instance, around 1984 the first video and computer game advertisements targeted boys—it’s no coincidence that the popular game console released by Nintendo in 1989 was called Game Boy.

When the capitalistic system met computer science, women were essentially expelled, with the knowledge they had cultivated violently appropriated. Importantly, it’s not the first time we see this kind of process. In Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici describes how the emergence of “professional medicine” was tied to the witch hunts. Between the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th, women were still practicing forms of popular medicine, based on the empirical use of herbs and natural remedies. With these women now socially stigmatized, as witches, the field of medicine came to be a highly professional domain that only educated people could aim to practice.

Nowadays in most Big Tech corporations technical roles are covered, in the vast majority, by men: of all the work positions, only 33% of them are covered by women; This percentage is even lower if we look at the technical roles, with an astonishing 25%. In the AI field, of all employed, women cover only 26% of the positions. But the most shocking data is that in open source jobs, the percentage of women is even lower, less than 10%.

A sociological study from 2016 on GitHub— a platform that allows programmers to share their code and get suggestions from others —showed that women’s suggestions are more likely to be adopted than men’s: 78% against 74%. Interestingly, if the gender of the person is disclosed, then the percentages are inverted. The gap is not very big and the aim of the study was not to answer whether women can write good programs or not, but to show that gender bias is still very real— also in communities that value cooperation, like the open-source one.

Who is a Programmer?

I recently found out about “brogrammer” culture. The brogrammer is essentially a mix and match of the worst aspects of the frat boy and the stereotypical programmer. Apparently, in order to make programming cool, someone in the 2010s had to invent a figure that never really existed before. Essentially, this produced some kind of frankenstein that mixed and matched the worst aspects of the frat boy and the stereotypical programmer. Toxic masculinity is a fundamental ingredient of this recipe: a brogrammer can “get all the girls” he wants while being rude and careless, but it’s justified because he is a genius. His greatest aim in life is to make a lot of money so he can acquire infinite power—while always wearing the same t-shirt. To put it shortly, this stereotype reinforces the most widespread understanding of what a man should be: powerful, self-made and impassive in the face of emotions. In result, women are discriminated against and sexualized, and the general approach to the field continues—despite its claims to the contrary— to be far from progressive.

And we don’t even have to go all the way to the toxic archetype of the brogrammer here. The stereotypical programmer is generally portrayed as a person with sociopathic tendencies: closed in their room, detached from society, people and their dynamics, and at times even actively angry at society. It must be asked, how libertarian tools can be built by someone who doesn’t know and understand society, and doesn’t think of themselves as part of it? People who aim at a beautiful and free life, and search for it, should love society, even if it has many contradictions and is deeply oppressed. This programmer stereotype, that we continue to fall back onto, ends up being a tool for governments and dominant systems. For them it is indeed useful to have at their service an army of skilled people with very little social and political conscience.

For example, around Valentine’s Day I read numerous articles about AI girlfriends and boyfriends. The claim is that it is now possible to use generative AI through some dedicated online platforms to create the perfect partner for the user. The user can choose how to shape their partner’s ‘body’ and character; except for physical touch, everything is allowed. I think this is a great example of how the patriarchal approach to technology can manifest itself: the idea that the infinitely enriching human experience of love could be reproduced through an algorithm—zeros and ones—lacks emotional intelligence.

Emotional intelligence is usually more developed in oppressed groups, as it fosters solidarity and empathy; women can and should bring it to the table. Exploring human emotions and interactions can be hurtful, but it is an essential way through which we get to know the community around us, and can therefore build tools to make people’s lives better. Isolated people are much more easily absorbed into the tornado of the capitalist system, which forces people to aim for profit, no matter the ethical consequences.

Technology and Political Neutrality

Let’s not forget about the political frame of technology and science. Liberalism is hiding it behind the thick curtains of an objective science, which supposedly distinguishes STEM studies from every other field. This is a lie built to allow systematic exploitation of resources and new inventions, which are alienated from their social value and collective dimension, to keep the war going. If we understand war not only in the military sense, but as a process to break societal bonds and the ability to self-organize, the use of technology by many governments and big tech companies fits well into this frame.

Technology is a tool: what matters is not only the use we make of it, but also the way and the purpose with which it has been developed. Everything that we design and produce as a society will mirror our belief system and we should remember that the scientific field is no exception.

Liberal ideology is telling us that women who can vote and work are free women in a free society— or at least freer than other places. To some extent this can be considered true, as oppression of women has really discouraging developments and consequences all over the world; but on the other hand, salary work has simply been added on top of care responsibilities, which remains a field mainly delegated to women. So although salary work for sure means the possibility to have economic independence, it also results in a doubling of the workload. And in the meantime, women are continuously confronted with unreachable standards of beauty, richness, happiness—standards that for the most part were not defined by women themselves. Women are highly targeted by social media algorithms that reinforce these standards and by percentage, they use Facebook, Instagram and TikTok more than men do. Social media is partly designed to break self-esteem and confidence of individual women; women start to feel like someone else’s success is a threat for them. Therefore, social media ends up nurturing a culture of competitiveness that breaks women’s collective bonds. It essentially enforces isolation, fragility and the feeling of loneliness.

Yet this does not mean that technology should be considered bad per se. Technology is a tool: what matters is not only the use we make of it, but also the way and the purpose with which it has been developed. Everything that we design and produce as a society will mirror our belief system and we should remember that the scientific field is no exception. It’s therefore important for each and everyone of us to be conscious of the scope of any new advancement, and carefully ponder what consequences it may have.

Shaping the Digital Revolution

Meanwhile, technology has taken up a fundamental role in our lives. It is said we are living in the era of the “digital revolution.” So, what does revolution mean?

Şervîn Nûdem, member of Jineolojî Academy1, offers an interesting perspective regarding this question: “A revolutionary movement cannot only have the objective to reach some political goals, it must also change the quality of life.”

Revolutions are supposed to change the way we think, organize, and produce. So, indeed, they are filled with political meaning. As for now this digital revolution is just another advancement in surveillance capitalism2. Until we will be able to break with dynamics imposed and taught by the patriarchal and capitalist system, this revolution will not change the quality of life for the better —to the contrary it will likely worsen it. With the exception of the small percentage of people who always benefit from others’ disgraces, mainly in the economical sense.

A strong example of what this “digital revolution” looks like is police crime predicting algorithms, which are built on racist and discriminatory social foundations and, as such, serve to further institutionalize them. Lawyer and writer Lizzie O’Shea talks thoroughly about this in the third chapter of Future Histories: “These biased data sets and algorithms, when used in a law enforcement context, have significant consequences. They generate a feedback loop shaped by racism and institutionalize certain understandings of risk. Both of these serve to confirm and exacerbate discrimination by oversampling people who are already discriminated against, generating even more biased data that justifies further discrimination.” As said before, technology does have a political frame.

Regardless of the situation, we need to maintain the belief that technological advancements can’t be fully absorbed into the dominant system. One outpost of resistance may be found in the recent Lunarpunk movement. Emerging over the last few years, the movement has its roots in cyberpunk ideology, which holds a libertarian vision of technological aided liberation. Lunarpunks build anonymous and encrypted tools, forging a path for collective freedom at a distance from state and big tech control. As the system gets stronger and finds ways to absorb people into its death machine, autonomy grows in turn, giving people the tools to gain back agency over their lives. Resistance will never die.

Technology also has an incredible potential for social transformation. But in order for this potential to be realized, we need to break the pervasive patriarchal mentality; we need to break sexualization and all forms of discrimination against women. And we need to do this not only because it affects women, but because it affects everyone. Keeping women away from the tech field means keeping new perspectives, resources, dynamics and solutions away.

The more I researched and thought about the issue of women in STEM, the more I became conscious about how much we need this change in perspective. I think that no sphere of life should be a stranger to women nor peoples of other gender identities—it’s not a question of simply reaching pink quotas3.

Technology will surely play a predominant role in our future and therefore how we approach this question will determine how our world and our society will be shaped. Both the perspective of women and other nonconforming gender identities are needed not only to recover gender gaps, but to construct freedom through and with technology.

- Jineolojî is a structure of the Kurdish Women Movement which has the aim to write history and sciences from the perspective of women. ↩︎

- The concept of surveillance capitalism was popularized by the Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff and it describes the mechanisms of data extraction and manipulation aimed at producing profit for big tech companies, which also have the effect of heavily limiting freedom of speech and right to privacy. ↩︎

- “Pink quotas” refers to the idea that every group should have at least a fixed percentage of women; the problem is that the group does not feel the need for this, so this ends up being an empty attempt not to look sexist. ↩︎

Valentina Ramanand

Feminist activist focused on trying to find and build antipatriarchal perspective within herself and fields she’s interested in, such as technology and economy. Currently studying informatics in the University of Milan.